In this post I use one large village in Sussex and it surrounding landscape and manorial estate as an exemplar of what has happened to many places in Sussex. I am calling this town by a fictious name name, Tollingly, and the estate around it, the Totworth Estate. All the data here are correct for the real town and the real estate to the best of my knowledge

House prices in Tollingly are on average £507,085 according to one estate agent. According to another, the majority of properties sold in Tollingly are detached and average price of a detached house is £843,568 based on a set of recent sales.

The average salary for an agricultural labourer/farm worker in the UK is £18,000 to £25,000; https://nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/job-profiles/farm-worker The average salary for an arborist in the UK is £25,000 to £35,000 is https://nationalcareers.service.gov.uk/job-profiles/tree-surgeon

Assuming the average property value in Tollingly is £675, 326.5o, the average salary of a farm worker is £21,500 and the average salary of an arborist is £30,000, an average house in Tollingly is 31 x the average salary of a farm worker and 22 x the average salary of an arborist. The maximum multiple of salary for a mortgage is typically four to five times your annual income. NatWest Mortgage Availability

According to a housing needs survey of Tollingly, the majority of properties in the parish are semi-detached or terraced (46.77%), with a slightly smaller number of detached properties (37.67%). Flats/maisonettes are fewest in number and constitute only 14.91% of the total housing stock. The 2001 census data revealed there to be 17 second homes within the parish (0.65%). From the 2001 Census data … the predominant tenure in Tollingly is owner occupation, with rates much higher than the rest of the UK: owner occupied 81%, Housing Association/Council rented 10% Privare rented 8.7%. According to the local authority responsible for social housing in Tollingly, social housing availability in Tollingly is very limited due to high demand exceeding supply : applicants face long waiting times. The average monthly rent for a private rented two-bedroom house in Tollingly is around 1£267, while a two-bedroom flat averages about £1217 and for a three-bedroom flat, the average is approximately £1367

So in effect there are hardly any people who live in Tollingly who are poor; making rural poverty elsewhere in Sussex invisible to middle class people living in Tollingly. In my road in Brighton poverty is in your face; I live in a terraced house worth ca. £450,000; 50m from my house is large social housing estate where 43% of children live in poverty.

Rural poverty in Sussex is a significant issue, particularly regarding specific challenges like fuel poverty and housing affordability, rather than being consistently higher in overall income deprivation compared to urban centres like Hastings and Crawley. Tackling Poverty Sussex Community Foundation

Tollingly Parish is a desirable, historic market town in … Sussex, characterized by its picturesque location; … and a prosperous community. Its affluence is reflected in the low levels of deprivation and high rates of self-employment and professional occupations. According to a District Council Management Plan

Tollingly used to have a livestock market; I used to go there sometimes with my grandfather (a wholesale butcher who, when his business went bust, was an agricultural worker on a farm with tied accommodation on the farm; when the land owner sold the land of the farm and his tied accommodation to a property developer he was made homeless with no compensation). The livestock market closed in 1974. Tollingly still has a market, a “Farmers Market”. When I attended the livestock market there were farmers and agricultural labourers there. The “Farmers Market” has no farmers or agricultural labourers; ii is a market of small-business food providers selling very expensive specialist food items for middle-class buyers; e.g. a stall (with artisan in the title) selling ars of Ruby Kraut for £10.45. “Farmer” has become a signifier of expensive, as has “artisan”.

When I was in my early in the early 70s I used to help my grandfather deliver meat on a Saturday to Brighton and Hove’s many butchers. The meat was sourced directly from Sussex farmers or from Sussex meat markets. The animals didn’t travel long distances, the farmers got a fair price and the meat from butchers was affordable. Now the few butchers that are left are only affordable to wealthy people. Poorer people buy meat from supermarkets that have sourced their meat from agribusiness, that treats animals appallingly, cause huge carbon consumption, cause loss of many farm workers jobs through mechanisation and rip of local small farmers – if they are used at all. (N. B. my Grandfather did pay me for my labour, including a huge greasy spoon fried breakfast in the Elm Grove transport cafe, Brighton).

The gentrification of country towns and rural areas in England has led to the social and economic displacement of working-class people. This process, often referred to as “rural gentrification” or “middle-class colonisation,” has been ongoing for several decades and has significantly reconfigured the social landscape of many rural communities. In many parts of the UK and in particular England, the dual pressure of restrictive housing supply and the effects of in-migration, have resulted in acute affordability issues for local communities (Best & Shucksmith, C2006). In the UK case, supply has tended to be outstripped by increased demand from commuters, retirees, second home owners, and those buying properties as holiday homes (Gallent & Tewdwr-Jones, 2000; Shucksmith, ). Those purchasing properties for these purposes tend to be in-migrants to the area, with greater buying power, who can out-bid local residents, resulting in rises in house prices beyond the reach of locals. Scott, M., Smith, D. P., Shucksmith, M., Gallent, N., Halfacree, K., Kilpatrick, S., … Cherrett, T. (2011). Interface. Planning Theory & Practice, 12(4), 593–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2011.626304

Gentrification of rural land has been happening for ca. 200 years since the coming of the railways. Grand middle class settlements were built on ‘waste’ and farmland nesr rail stations. e.g. Croborough, Groombridge, Tunbridge Wells

“All through that 19th century middle class incomers were settling along the railway lines…such as in the mid-Sussex towns…and along the previously deserted Sussex coast. Every village and market town and the hinterland of every rural railway station had its villas and posh semis. Farmsteads were being taken over by the well-off (such as Cotchford Farm, by the author of Winnie the Pooh), and farmland taken out of food production and replaced by amenity uses.” (D. Bangs, personal communication, November 24, 2025)

According to the latest data on the agricultural workforce in England, there was a 4.6% drop in full-time regular workers to 41,000 in 2023, meaning 1,886 left the sector. This equates to an average of 36 a week. Farmers Weekly Agribusiness – by buying up small farms (with hedgerows) – have turned much land nto monocultural deserts, allowing mechanisation to decrease the need for workers – which is in part responsible for loss of agricultural labourers jobs. See Employment impacts of agrifood system innovations and policies: A review of the evidence Julio A. Berdegué, Carolina Trivelli, Rob Vos, Employment impacts of agrifood system innovations and policies: A review of the evidence, Global Food Security, Volume 44, 2025, 100832, ISSN 2211-9124,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2025.100832 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211912425000070

Supermarkets control pricing of purchases from small farmers; big business’s control over the food market means small farmers receive less revenue which reduces the number of agricultural workers farms can employ 60% of farmers ‘at financial risk from supermarket buying behaviour’ . Josie Clark November 2025 The South East (including London) region has 35,200 farms of all types in 2023/24. HM Government 50% of all UK holdings are under 50 acres

While elements of the “no farmers, no food” campaign have been captured by right-wing and reactionary groups peddling conspiracy theories, these groups are playing on genuine concerns. In the UK, farm income varies hugely across types and sizes of farm but, particularly among smaller operations, many farms are not particularly profitable Alex Chapman 2024 New Economic Foundation Flights, farmers and food. Our government’s greed for ever more air travel could come back to bite them

Just outside Tollingly is a voluntary project: the Tollingly Countryside Project, on the land of the local estate: The Totworth Estate. The Totworth Estate has 16th-century Grade I manor house; a home for the landed gentry. The estate is owned by the same family who acquired it in the 18th century; comprising of over 6,000 acres, some of which is farmed in-hand by the estate, and a significant portion is leased to tenant farmers. The estate must get considerable revenue in rents. On the Totworth Estate website it mentions no in-hand farmers or agricultural workers, just people involved in its wine business, forest workers and workers in their restaurant (£85 for a two course meal). The website implies that the estate is focussed on wine production and wine retail

Vineyards are associated with negative environmental impacts. Traditionally, vineyards are intensively managed, involving a high level of pesticide application and the simplification of landscapes, which reduces the diversity of vegetation and crop types. The production and application of pesticides contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, and pesticides can also pollute waterways and soils. More so, the way the vineyard land is worked, together with the land-use change brought on by vineyard implementation, can cause disturbances to soil health and biodiversity. Ebba Engstrom, 2023, Grantham Institute (Climate and Environment) Imperial College London.

A woodland SSSI is also on land owned by the Totworth Estate; there is very little access for the public. Totworth Estate also has pheasant and partridge shooting on its estate; cost: £2195 per gun for a bag of 250 pheasant. There are four shoots a year (in the hunting season) with eight places on each. That brings in revenue of £70240 pa. The estate self-declares a Christian ethos; God inspires their conservation. There is a sign in one part of their estate that says: “Look at the birds in the sky. They never sow nor reap nor store away in barns, and yet your Heavenly Father feeds them. Aren’t you much more valuable to him than they are?” Jesus of Nazareth. Clearly their god doesn’t like Pheasants or Partridges. But maybe there is a clue in this quote of their underlying values: people are more valuable than birds. The release of pheasants and partridges into the environment causes great ecological harm. Pheasants and Partridge shooting is only available to rich people, causes great environmental damage and denies the general public of all incomes access to the land the shoots take place on

The RSPB has growing concerns about the environmental impact of large numbers of gamebirds being released into the countryside. Our main concern is with large-scale shoots which release high densities of gamebirds which can be damaging to the environment including through:

- direct impacts, such as browsing of plants, predation of reptiles and invertebrates, competition for food resources eaten by native wildlife and soil enrichment.

- Disease transmission to wildlife, like the Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (bird flu)

- Changes to the balance of predators and prey of threatened species (gamebirds can be a supplementary food source for predators, such as foxes)

- Shooting practices, including lead shot that pollutes the environment, is ingested by scavengers and can enter the food chain. RSPB

The Tollingly Countryside Project (one employee allocated to manage it on the Totworth estate payroll) offers opportunities for volunteering; conserving and managing the land. The Tollingly Countryside Project has over 100 volunteers. I believe that volunteering is important, as much for volunteer’s wellbeing as for the the good they do for the environment and this attested in research: volunteering improves well-being according to NCVO Time Well Spent: A national survey on the volunteer experience

Nationally, individuals of 65–74, with higher levels of education and income are generally more likely to volunteer. NCVO demographics of volunteering. Statistically people with higher incomes and are retired experience the highest levels of wellbeing. WHO Determinants of Health and poverty negatively impacts wellbeing through increased stress from financial insecurity and poor living conditions, leading to higher rates of poor physical and mental health. BMA: Health at a prive: Reducing the impacts of poverty

It is very likely then that the vast majority of volunteers for the Tollingly Countryside Project are middle class and are already experience higher well-being than people living in poverty. Poverty and wellbeing are strongly linked, with poverty causing poor mental and physical health through factors like financial stress, poor housing, and inadequate nutrition The King’s Fund The Tollingly Countryside Project does little for people on low incomes because there are few people on low incomes in their area. It is a project for middle-class people

But a number of studies have shown that low pay is more prevalent and more persistent in rural areas than urban areas. e.g. Chapman, P. and Phimister, E. and Shucksmith, M. and Upward, R. and Vera-Toscano, E., 19991805622, English, Miscellaneous, UK, 1-899987-67-3, York, Poverty and exclusion in rural Britain: the dynamics of low income and employment.(1998).

Low pay’s prevalence in rural areas is thought to arise partly due to employment in low-paying sectors such as agriculture. Chapman, P., Phimister, E., Shucksmith, M., Upward, R. and Vera-Toscano, E. (1998) Poverty and exclusion in rural Britain: the dynamics of low income and employment, York: York Publishing. But in Tollingly there are few people employed in agriculture.

So the Tollingly Countryside Project provides opportunities for well-off people, mostly retired, who are already statistically happier than poorer people, to volunteer and increase their well being.

All well and good, and there is value in that, but if the Totworth Estate used the money it donates to the Tollingly Countryside Project and employed agricultural workers to do what the volunteers do they could increase the well-being and income of poorly paid agricultural workers; but I don’t think there are many/any agricultural worked who live in the Tollingly area; as they couldn’t afford to live there. Moreover, the donation that Tollingly Countryside Project receives from the Totworth estate is relatively small; the total donations, from appraising their most recent financial statement, is around £50,000 – there are not many people you can employ with that.

However, the Totworth Estate’s website says it employs 70 people. A third-party business analysis website estimates the winery revenues at £7,000,000. The Totworth estate does not publicly lists its accounts; so it hard to know what profits they make after expenses are taken into account. If those 70 people are on the average rate of pay in the UK (£38,100) so the staffing costs for the estate is approximately £2,667,000. It would appear that most of their employees are engaged in wine making; but they have three employees in the forestry team and one employee who manages the Tollingly Countryside Project. So it would appear that the majority of the effort of the estate is focussed on wine production. A bottle of their best-selling wine costs £36 so that effort is focussed on middle-class consumers.

It would be very hard now to increase the employment of workers on agricultural land. “Farmers remove their workers and replace them with giant and expensive machines in just the same way as every other industry does under capitalism. The ‘law of value’, capitalism’s ‘hidden hand’, dictates that they do so. Each unit of capital has to compete with other units of capital, and profit is to be made on labour, not on the machines themselves. They are therefore driven to increase the rate of exploitation of labour by innovating technically and replacing relatively unproductive-but-widespread manual labour by hugely more productive machine-minding labour; right up the point when site-based labour is replaced entirely by the robot machine (in milking, harvesting, planting, ploughing, sorting, adding value), so that the farmer’s profit comes from just his own family’s labour and the labour of the people who made the machines” D. Bangs, personal communication, November 24, 2025)

The Tollingly Countryside Project is a project mainly funded by the Totworth Estate. The stated aims of the Tollingly Countryside Project is to create inspiring opportunities for anyone to join in, through active volunteering, engaging events and inclusive access. An interpretation of Totworth Estate setting up Tollingly Countryside Project is class washing: a narrative that downplays social class distinctions and inequalities, presenting a false sense of a “level playing field”; the Totworth Estate uses Tollingly Countryside Project to disguise the class privilege of the estate and the people who live in Tollingly.

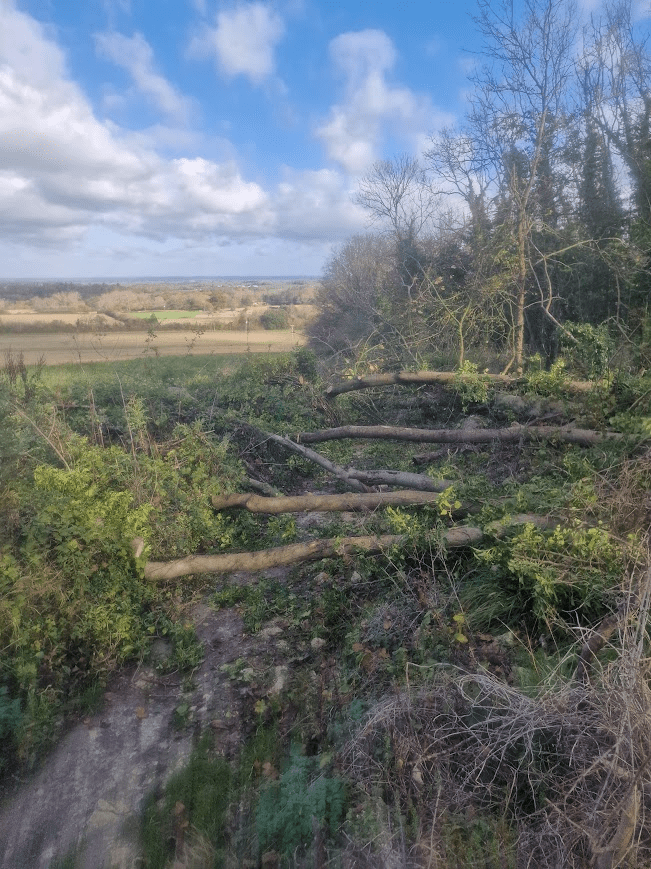

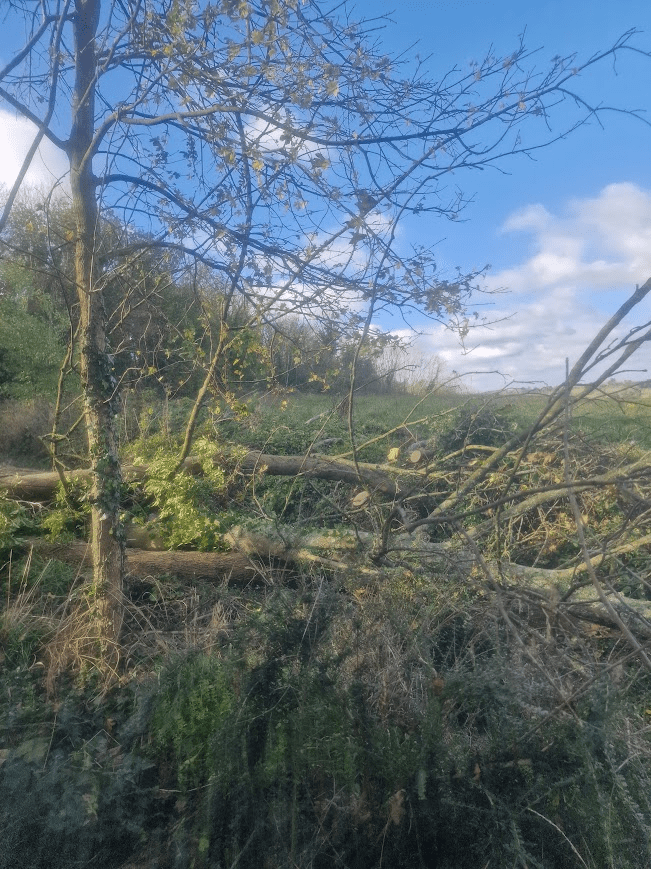

One of the responsibilities of a landlord is to maintain public rights of way through their land; this is a statutory duty. Walking on a path is something that you can do irrespective of your wealth or income – it is a free pleasure. Recently I was walking through the estate on a public footpath and it was blocked with ca. 15 ash trees that had been felled. The trunks with their branches were laying across the path. It is a criminal offence to block a public right of way. I emailed the forestry team of Totworth Estate and the local authority about the blockage. In the absence of a right to roam public footpaths are often the only access you have to land; so it important that they are usable. Instead of using their foresters to remove the trees.

I soon had a reply from the manager of Tollingly Countryside Project saying that the children from a local school were going to clear the ash; with the comment “it is us getting the manual work done for nothing”. Children can not use a chainsaw (which was obviously used to fell the trees); cutting the trunks and branches with hand saws is heavy manual labour for adults let alone children. I think there is great value in children learning outside, in woodland, in meadows, on farms etc. But is it safe to get children to do heavy manual work Moreover, clearing public rights of way needs to be done quickly and efficiently, to meet a landowners statutory responsibilities; i.e. by paid workers, not children, or volunteers.

The social milieu of Tollingly and its environs is middle class: high cost housing; opportunities for game bird shooting; opportunities to quaff high-price wine or buy high cost food items. It’s not surprising almost no working class people now live in the Tollingly area: there is little work and housing that is only affordable to the wealthy. The Tollingly area seems to have been colonised by middle class people; supported by the landed gentry; erasing the working class people who used to gain a living from the land.

We need a new model of agriculture that is democratic, and in community co-operative ownership; employing local people, growing food for local people; we need to end our reliance on imported cheap food that is carbon polluting and gives great profit to international agri-business and supermarkets. We need food security, and affordable food, that meets the food and employment needs of ordinary people. We don’t need the big-business model that leads to the destruction of nature and the impoverishment of people. Nor do we need the landed gentry (aided by misguided ecologists) taking land out of food production to rewild it as a hobby. Saving nature is about regenerative farming not introducing storks so that middle class people can expensively “glamp ” to see them in a “shepherds” hut at £350 for two nights to see them.

I am not sure how we get there; but Aaron Benanav: ‘Beyond Capitalism -1. Groundwork for a Multi-Criterial Economy’ & ‘Beyond Capitalism – 2. Institutions for a Multi-Criterial Economy’ in the New Left Review offers a nuanced understanding of how we get beyond capitalism . Aaron Benanav explains multi-criterial economy in discussion at https://wissenschaftspodcasts.de/podcasts/future-histories/s03e50-aaron-benanav-beyond-capitalism-i_10021691/