Whilst this post specifically addresses issues concerning the impact of class structure of the Sussex landscape on lichen distribution, conservation, and access to nature, class structure of the landscape impacts on the conservation of and access to all nature.

The existence of “high quality” old woodland lichens and access to them are partly a function of the class structure of the Sussex landscape. The “best” (or what is considered as best) corticolous/epiphytic (tree) lichens in Sussex are often in places that were owned, and in some places, are still owned, by the aristocracy; often descendants of the feudal barons who were allocated land by William the Conqueror in exchange for military service and loyalty.

The distribution of lichens in Sussex, and current access to see them, is intrinsically linked to that class structure of the landscape. Old parklands (deer parks) of pasture woodland, and ancient tall forest woodland, like Ashburnham Park, and ancient coppiced woodland (coppice with standards) are some of the best places to see old woodland lichen species. Aristocratic medieval deer parks (the larders of the rich) entailed pollarding; pollarded pasture oaks live longer, thus have long ecological continuity, and have lots of light, which is propitious for lichen growth and survival. Having a deer park was a function of wealth, and intrinsically linked to the feudal class structure of the mediaeval and early modern periods. Tall forest ancient woodland in aristocratic estates are also good for old woodland lichens because of the length of ecological continuity, although many former ancient broadleaved woodlands have been replanted with Sweet Chestnut or pines, were profit trumped conservation of ancient woodland. The part of Ashburnham we visited was ancient tall forest woodland; we have yet to visit the parts of the SSSI which were pasture woodland.

The survival of pasture woodland, tall forest ancient woodland and coppice with standards woodland in the modern period is dependent on the actions of aristocrats, or of the new rich landowners who bought aristocratic land holdings. Many historic park woodlands and ancient tall forest woodland have been partially or completely destroyed by cash cropping i.e., the replanting of ancient woodland with Sweet Chestnut (e.g. Flexham Park and Fittleworth Wood) or conifers (e.g. Worth Forest), or sold for development (as nearly happened at Old House Warren). Once vast [ancient woodland] now cover just 2.5% of the UK. Around half of what remains has been felled and replanted with non-native conifers and even more is under threat of destruction or deterioration from development Woodland Trust

Moreover, access to remaining historic ancient pasture woodland, tall forest ancient woodland and coppice with standard woodland is dependent on the ownership of the Sussex landscape. Some woodlands have public access; some of those are in public ownership but local authorities or the ownership of conservation charities e.g. Bexhill Highwoods (coppice with standards), Petworth Park (pasture woodland), and Marstakes Common and Ebernoe Common (pasture woodland and high forest woodland). Marstakes and Ebernoe Commons’ pasture woodland are not related to keeping deer but pre-enclosure commoners’ rights to common grazing, often pig grazing (pannage), which still, though, entailed the largesse of aristocratic land owners. Common land was “manorial waste” and was poor quality land within a manor that was not cultivated or enclosed, and over which tenants and other individuals had rights of common, such as grazing or gathering resources.

Much woodland in Sussex landowners is still owned by it original aristocratic families; some have partial access on limited public footpaths e.g. Eridge Park and Buckhurst Park, and some have no public access e.g. Paddockhurst Wood, Pads Wood and East Dean Park Wood; the latter due to its use for shooting for profit, the curse of public access to woodland in Sussex. Ashburnham Park is an anomaly; it is owned by a Christian trust, for study and retreats, and is currently pretty permissive of public access through a network of private footpaths on the estate. Long may that remain!

The Ashburnham family were lords of the village of Ashburnham, and elsewhere, for some 800 years. The village itself was Esseborne in Domesday Book (1086) and Esburneham in the twelfth century; the name is thought to mean ‘meadow by the stream where ash-trees grow’. By about 1120 the family had taken its name as their own. It may be that the first of them may have been the feudal lord of Ashburnham in 1086 – Peter de Creil or Criel or Crull, a Norman immigrant awarded land by the Conqueror. For almost all of the remaining time up to living memory – with two intermissions – the Ashburnham estate was owned by this one family. The second such intermission led to a peerage; the first (1611 to 1640) resulted from disastrous financial management. Battle and District Hisotrical Society Archive, George Kiloh, 2016,

From the Historic England Ashburnham listing:

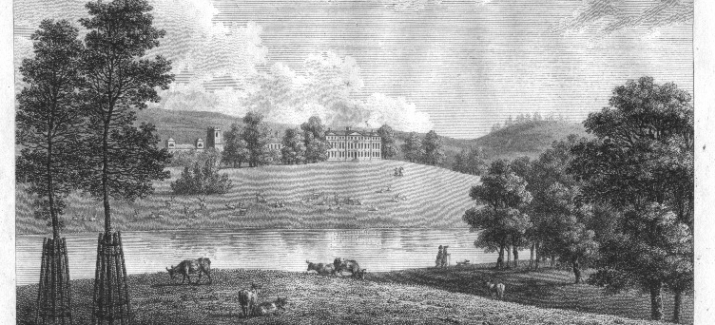

In 1665, John Ashburnham built a new house on the site of the present mansion, replacing an older house. He died in 1671. His nephew was created Baron Ashburnham, the baronetcy becoming an earldom in 1731. The second Earl reconstructed and enlarged the house between 1759 and 1763 and commissioned Lancelot Brown (1716-83) in 1767 to lay out a new park and gardens around the house of which the lakes and much of the planting structure survive.

The third Earl succeeded in 1812, his additions between 1812 and 1817 including the terraces to the south and east of the house and the bridge across Front Water. The sixth Earl died in 1924 and the line ended with the death of his niece, Lady Catherine Ashburnham in 1953. The Rev J Bickersteth, a grandson of the sixth Earl, inherited the estate and in 1960 gave Ashburnham Place and 89ha, including the main gardens and pleasure grounds, to the Ashburnham Christian Trust.

Ashburnham Place (listed grade II), with St Peter’s church (listed grade I) immediately to its west sits on the north-west slope of the valley, overlooking the chain of lakes and the park woodland beyond. Although the house is truncated from its C18 form, with the church (rebuilt to its present form in 1665) and the stable block (built between 1720 and 1730 and listed grade II*) a visually cohesive group of buildings is created. The house was built in 1665 and enlarged to its final form by 1763 with the addition of the domestic wing facing the church, the long range of state rooms which made up the south front. Brown’s greenhouse, with seven bays (now the Orangery, listed grade II), stands attached on the west side. The brick house was refaced twice, once in 1813 by George Dance and again in 1850 with the present red and grey brick. The house had reduced to a state of decay by the mid C20. It is now about three-quarters of its former size, the remainder having been demolished in 1959. The present (1990s) owners have made considerable additions from the 1960s onwards, on and around the house’s previous ground plan. Brown’s Orangery survives intact .

The Ashburnhams’ wealth came from rents from their extensive land holdings; but also from the Wealden iron industry, including the manufacturing of arms. This is a feature of many other Wealden aristocratic estates, and had a significant impact on woodland in Sussex. The High Weald wasn’t always a pastoral/arable landscape (or the leisure landscape of middle-class wealth that it is now); the High Weald was an industrial landscape in the Tudor and Stuart periods (as it partly been during Roman exploitation of iron in the Weald). Iron ore was dug out of the weald clays, and wood was cut to make charcoal for the iron furnaces. The mill ponds (hammer ponds), which powered the hammers of the furnaces, were sometimes then converted into landscape features, such as ornamental lakes, e.g. at Leonardslee. Visiting the relict hammer ponds in Sussex is fascinating. The website Hammer Ponds details them. However, many of them can not be visited as they have been turned into private fishing ponds. The lakes at Ashburnham are not converted hammer ponds but creations of Lancelot “Capability” Brown who charged a lot to posh-up your estate and make it appear an arcadian paradise. Capability Brown’s work at Ashburnham Place involved significant costs, with direct payments to Brown totalling £7,296 (1753). Landscape Institute: Capability Brown: Ashburnham equivalent to £960,992.20 today.

Ashburnham Park in 1874. Curtesy of Landed Families

It cost the the 2nd Earl of Egrement a pretty penny too to get Capability Brown to landscape the Petworth deer park, and turn it into a simulacrum of the faux antique landscape paintings of Claude and Poussin, which hung in the Earl’s painting collection inside the neo-Palladian Petworth House. Capability Brown received five contracts from Lord Egremont between 1753 and 1765, totalling £5,500 (1773). Landscape Institute: Capability Brown: Petworth This is equivalent to over £1,051,136.88 in 2025.

Photos from Hammer Ponds: Ashburnham Forge

Part of the forge pond survives just to the west by a road on private land at 684161, with a modern weir. Looking down east from the bridge here, a rusty channel can clearly be seen far below, running under the conservatory of Forge Cottage. Hammer Ponds: Ashburnham Forge

North along the track down a detour right at the path fork (685172) there is a footbridge over a rusty ford with several large reddish ‘bears’ in the stream: a bear is a rock of imperfectly smelted ore and iron. Slightly further along, left in a private meadow, a high bank is visible. This is the old furnace bay, and the furnace pond, now dry, lay beyond it. This is now a low field. The old spillway is roughly halfway along the bay and still serves a stream – depending on the overgrowth, this may be seen as well as heard. Hammer Ponds: Ashburnham Forge

Ashburnham was an important Wealden complex of furnace, forges and boring mills, built by John Ashburnham before 1554, and the last Wealden furnace to close in 1813, although the forge continued until the late 1820s. The sites worked together during the Civil War, the premier Wealden ordnance suppliers until about 1760, and later produced guns and shot for the Dutch Wars. The main furnace pond is now dry, but a secluded pen pond survives on private land just north of the furnace site in Andersons Wood (685173). [The Ashburnham iron furnaces supplied arms to the Royalists during the civil war.]

An unmade road, heavily metalled with waste iron slag, runs about half a mile between this remaining furnace pen pond and the dry site of Ashburnham (Upper) Forge. Known originally as the ‘sow track’, this not only took sows and guns from the furnace down to the forge and boring mill but also extended up past Robertsbridge to Sedlescombe, where iron goods were shipped to London via the river Brede.”

Ashburnham forge was “…the most persistent of the Sussex works were those at Ashburnham, extending into the next parish of Penhurst, and obtaining fuel supplies from Dallington Forest. The furnace, which is mentioned in 1574 and was probably established much earlier, lasted till 1811, and the forge continued working until 1825. Mary Cecilia Delany, 1921; The Historical Geography Of The Wealden Iron Industry available online

As well as tall forest woodlands, there are many relict coppiced woodlands, some with relict with charcoal hearths across, the weald. Coppice with standards was the typical coppicing practice; and the standard (maiden) Oaks of these relict coppiced woodlands are important for lichens. Charcoal was critical to the production of iron. Coppiced wood (mainly oak, alder and hornbeam) was used to make the charcoal in round ‘clamps’ of 4-5 metres which were often constructed on levelled ground. The presence of nearly black soil and small pieces of charcoal can confirm past use [of land as charcoal hearths. High Weald National Landscape: Archaeology

The peaceful pleasure of walking through relict coppices belies one of the reason why those coppices were there: the Wealden ironmasters began to concentrate increasingly on gun founding, and examples can be found all over the world, wherever Britain fought or traded. Eventually, the onset of the Industrial Revolution took heavy industry north to the coalfields, and the last furnace in the Weald, at Ashburnham, closed in 1813. Wealden Iron: History. The Wealden coppices fuelled the furnaces that made the weapons the made Britain’s early modern imperial colonialism possible

Cast-iron guns were particularly needed by the government at this

time. … There are many references to Levett’s deliveries of guns and shot to the Crown in the 1540s. In 1546 he was paid £300 for making iron guns, and typical of his trade in ammunition is an order of 1545 for 300 shot for cannon. The Iron Industry of the Weald. Henry Cleere and David Crossley with contributions from Bernard Worssam and members of The Wealden Iron Research, Second Edition Edited By Jeremy Hodgkinson Merton Priory Press 1995. Available online

Coppiced woodland in the weald was not only used for charcoal to produce the iron that produced munitions, in places Oak was planted to be cut later for ship building. The thick multi-stems of relict coppiced Sessile Oak at Highwoods near Bexhill, provides the only opportunity to see lichens on coppiced Sessile Oak (Quercus petraea) in Sussex. But these Sessile Oaks were not planed for their beauty, or to be a substrate for liches, they were planted to build Henty VIII’s navy. Ship building has always had a strong reliance on natural resources and Britain would not have been able to conquer the seas without the abundance of wood that was available to construct its mighty vessels. … Overall, Britain built its place in the world through the power of its maritime endeavours, and in this way, the forests of Britain helped to build the nation that it became. This quotation from Rural History obscures the fact that the nation that the UK became because of its exploitation of oak woods for its naval ships, was a nation that ruthlessly subjugated people to colonial slavery.

A postscript: another class-based use of Wealden iron from Ashburnham:

The stocks and whipping post by Ninfield Green (TQ 707124, above) were cast locally in the seventeenth century, probably at Ashburnham. Hammer Ponds A Brief History of the Iron History

The lichens we saw are detailed in Part 1 of this post: Lichens of Ashburnham Park SSSI 12.06.25. Part 1: The Lichens.