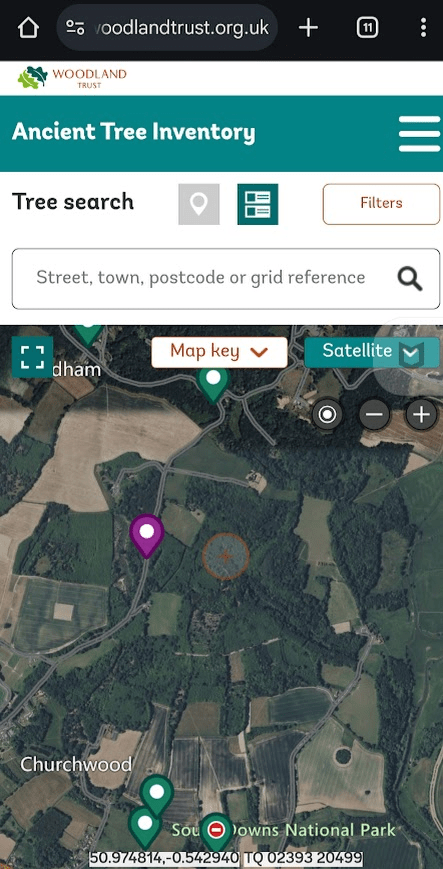

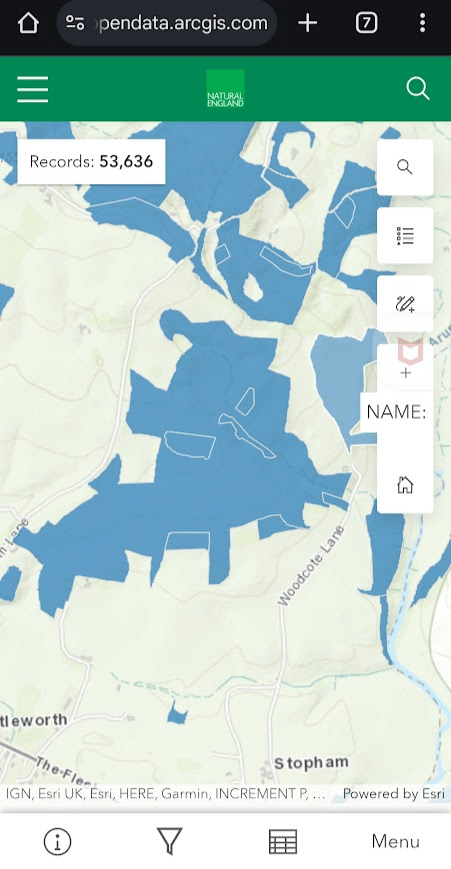

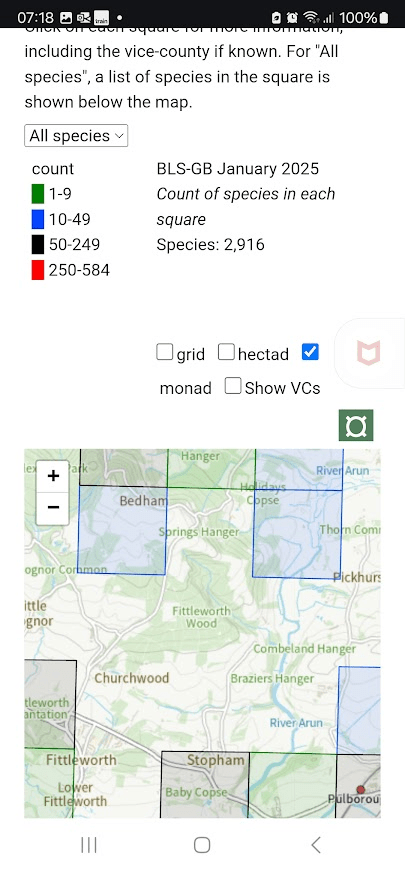

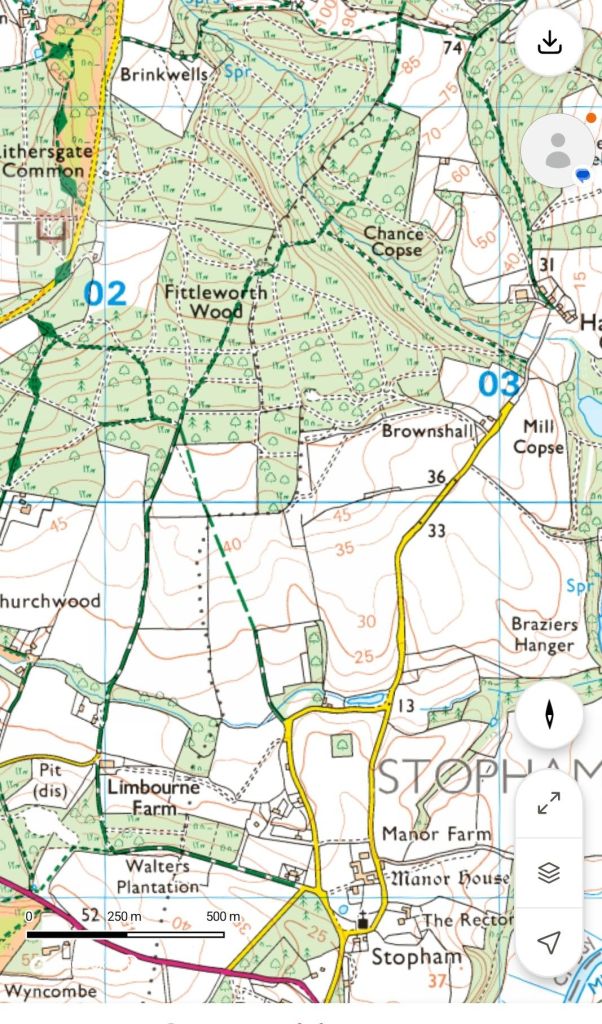

I visited with a friend, and fellow naturalist, a high weald ghyll wood to explores its bryophytes and lichens. This ghyll had the features of most high weald ghyll woods; a ghyll fed by springs from the sides of the ghyll valley. The springs form where the porous Tunbridge Wells sands, meet the Wadhurst Clay, of the impervious Wealden Group. These springs produce wet flushes which are a highly propitious habitats for bryophytes. Ghyll woods often have outcrops of Ardingly Sandrock, where bryophytes, ferns and lichens grow.

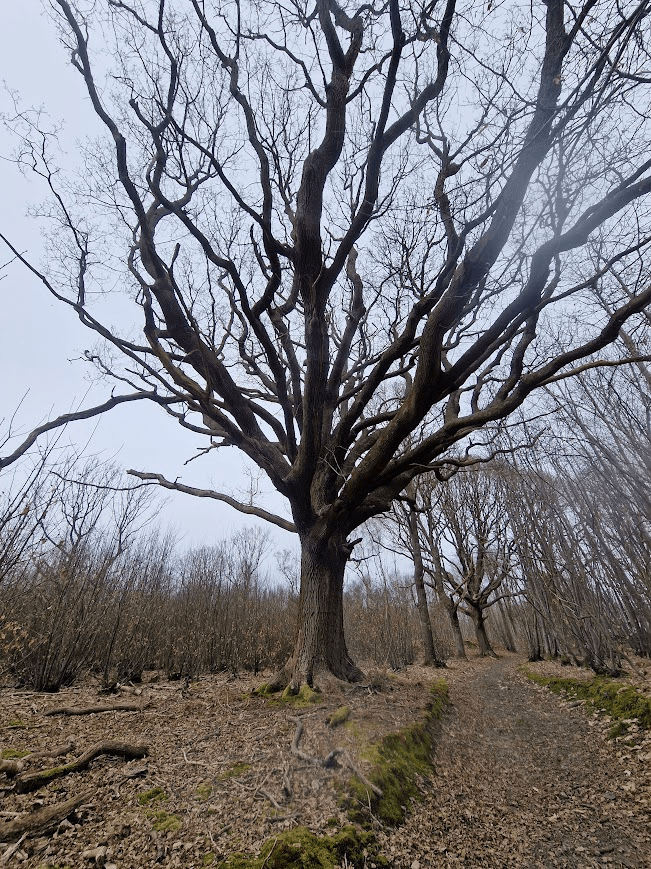

Most Ghyll Woodlands have ancient, veteran and notable tress; often Pedunculate Oaks Quercus robur, and Beech, Fagus sylvatica. This wood did, but only around the ghyll; other parts of the ancient woodland have been replanted with pines, often Scots Pines, Pinus sylvestris, and other trees for ornamental purposes and timber. Unfortunately much of the ancient woodland of the High Weald have been replanted either for landscaping or timber.

“Due to their isolation and enclosed nature, Ghylls have a unique microclimate, often rich in bryophytes and other moisture loving plant species. Ghyll woodlands are found in the extreme upper reaches of rivers, where springs and streams first form in small, steep, wooded valleys. The steep sided nature of Ghylls has also ensured that many Ghyll woodlands have remained untouched and undisturbed by human activity. Ghyll woodlands have an unusual micro-climate and they are therefore unique.

The flora found in these sites is very characteristic of former Atlantic conditions – including lush growths of ferns (such as Hay Scented Buckler Fern), mosses and liverworts. Many are likely to be primary woodland sites (potentially dating from the ice-age) and some have received relatively little disturbance, pollution or management. Ghylls provide an important function within the wider river catchment. They help to capture and slow down rainfall and overland run-off which would otherwise have a high capacity for erosion in these steep areas. They also provide shade and protection from sunlight, which provides a kind of ‘thermostatic regulation’ to downstream areas of river by cooling down water temperatures. Cool river temperatures are particularly important for the reproduction of a number of fish species.

Over 6% of the High Weald in Sussex is classed as ‘Ghyll’ woodland. This rare habitat type is a unique landscape feature of this part of Sussex and of the UK. Ghyll woodland in these terms specifically applies to the woodland found in the Sandstone and Hastings beds of the High Weald. There is currently no agreed definition of the riverine/floodplain limits at which Ghyll woodland becomes a floodplain woodland, and as such it is difficult to assign an accurate figure to the known area of Wealden and non Wealden Ghyll woodlands in Sussex.” Sussex Wildlife Trust – Wet Woodland

Bryophytes

Bryophytes are a group of plants that include mosses, liverworts and hornworts. Currently (January 2021), there are 1098 species of bryophyte in Britain and Ireland, which represents around 58 percent of the total European flora. Conversely, our islands have less than 20 per cent of the European flowering plants.

Like the ‘higher’ plants (flowering plants and ferns) the majority of bryophytes make their own food via photosynthesis and because they contain chlorophyll, the majority are green. However, bryophytes lack proper roots, structural strength and an advanced vascular system to move water and dissolved substances around efficiently and so are size-limited.

The mosses, liverworts and hornworts are believed to have evolved from ancestral green algae and are thought to comprise the earliest lineages of plants. Because of their unassuming nature and small stature, bryophytes are easily overlooked or even dismissed as boring, but their beauty and complexity under the microscope easily puts them on a par with their higher plant relatives. British Bryological Society – what are bryophytes

… bryophytes can’t grow very big because they have no way to efficiently move water from their base to the rest of the plant. Instead, they grow close to the ground and absorb water directly from the environment into their cells.

Despite their preference for damp habitats, bryophytes can live for a long time without water. Some plants … survive droughts by storing water, but bryophytes have a different strategy. They go into a state of dormancy, or suspended animation, and simply wait. Water … isn’t just important for hydration. Bryophytes rely on it to reproduce as well. … bryophyte sperm has to “swim” to an egg cell to fertilize it.

… mosses have a midrib in the middle of each leaf, whereas liverworts have no midrib. Liverworts are relatively flat in comparison to mosses because their leaves are in two parallel rows, whereas mosses tend to have a more spiral shape, with leaves emerging from all sides of the stem. … . Another feature to consider if you’re trying to distinguish mosses and liverworts is the presence of lobed leaves, or leaves with protuberances off the main leaf … Some liverworts (but not all) have lobed leaves, but no mosses do.. With mosses … one of the first questions to ask is whether it’s pleurocarpous or acrocarpous. Pleurocarp mosses … tend to have highly branching stems and grow in sprawling patches. The stems of acrocarp mosses, meanwhile, have little or no branching and grow mostly vertically, often forming tight clumps.

With Liverworts, one of the first question to ask whether its a thalloid of leafy liverwort; thallose liverwort, set apart from so-called leafy liverworts by the presence of thallus (a ribbon-like structure) instead of leaves. … Interestingly, liverworts also have a distinctive smell, sharp and earthy. The scent can be so strong that you might sometimes smell liverworts before you see them. Duke University Research Blog Into the Damp, Shady World of the Bryophytes

Some of the mosses and liverworts of this high weal wood:

Pleurocarp mosses:

Thamnobryum alopecurum Fox-tail Feather-Moss.

Growing at the base of a Pedunculate Oak

A shade-tolerant species which occurs in several distinct habitats. It grows on the ground, on exposed tree roots and tree bases in woodland and on the banks of ditches and sheltered lanes, occurring on mildly acid, neutral or basic soils but in particular abundance in woods over chalk, limestone and calcareous boulder clay. BBS Thamnobryum alepercurum

Acrocarp mosses:

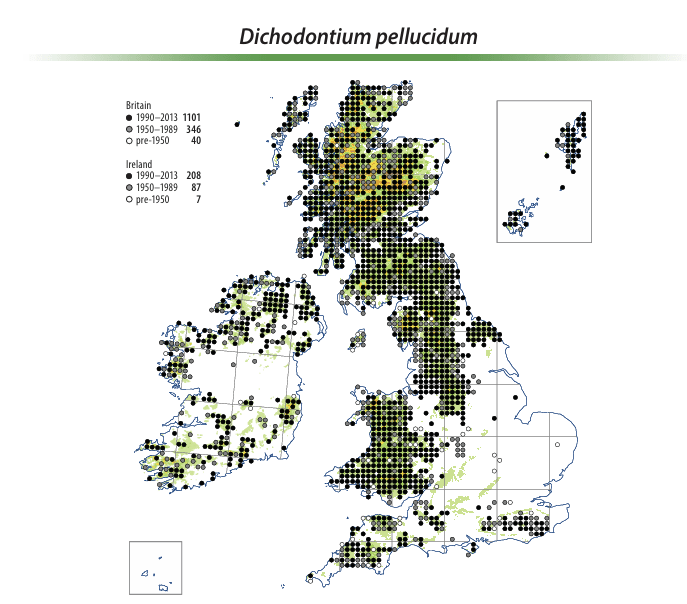

Dichodontium pellucidum Transparent Fork-Moss

D. pellucidum is a moss often growing on rocks by streams and rivers in the North and West (Atlantic Woodlands); but it is also found in the High Weald

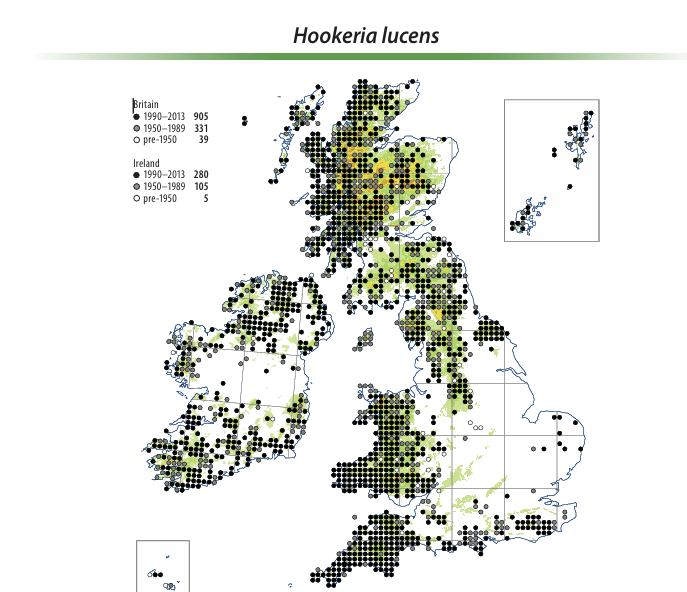

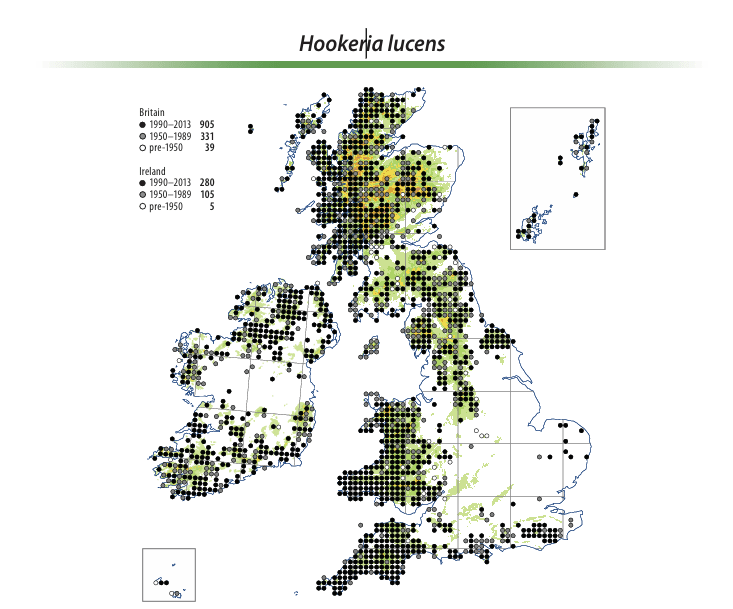

Hookeria lucens Shining Hookeria

A plant of shaded, moist, humid sites, found in flushes on woodland banks and on streamsides and riversides, of North and West (Atlantic Woodlands); but it is also found in the High Weald

Those who have not encountered Hookeria before are wowed by its beauty and distinctiveness but because it’s very complanate and quite large, may assume it is a leafy liverwort. However, it lacks complicate-folded leaves, underleaves, trigones, oil bodies and any of the other features that are often present in the leafy liverworts. BBS Hookeria luncens

Orthodontium lineare Cape Thread-Moss

Pogonatum aloides, Aloe Haircap

Although very common in the uplands, the species has declined in C and E England from the loss of suitably open acid substrates, although many of these loses are of long standing. BBS Pognotum aloides

This moss emerges from a low, persistent, vividly green protonemal felt.

The protonema is the first part of the moss that develops from the germinating spore. Its filamentous form is remarkably similar to green algae. This photosynthetic colonizer lies flat against its substrate, making it seem as if the rock or tree it grows on is painted green. University of British Columbia Introduction to moss morphology

Mala Rhizomnium punctatum Dotted Thyme-Moss

Its shoots come in two forms – sterile and fertile. The sterile shoots of Plagiomnium lie flat or low to the ground (procumbent or arcuate) and look somewhat flattened (complanate). Stem leaves are toothed. Sterile shoots of Rhizomnium are erect, and stem leaves are entire. In both genera the fertile shoots are erect.

Plants are dioicous and male plants of R. punctatum are particularly striking and resemble small flowers

Leafy Liverworts

Asperifolia arguta / Calypogeia arguta Notched Pouchwort

Cephalozia bicuspidata Two-horned Pincerwort

Chiloscyphus polyanthos Square-leaved Crestwort

This is one of the commonest leafy liverworts to be found on rocks and other surfaces in watercourses and lakes where it usually grows at least partially submerged. You’re unlikely to find it in chalk or limestone streams or in other base-rich water as it prefers water with a pH of 6.5 or less. BBS Chiloscyphus polyanthos

Diplophyllum albicans White Earwort

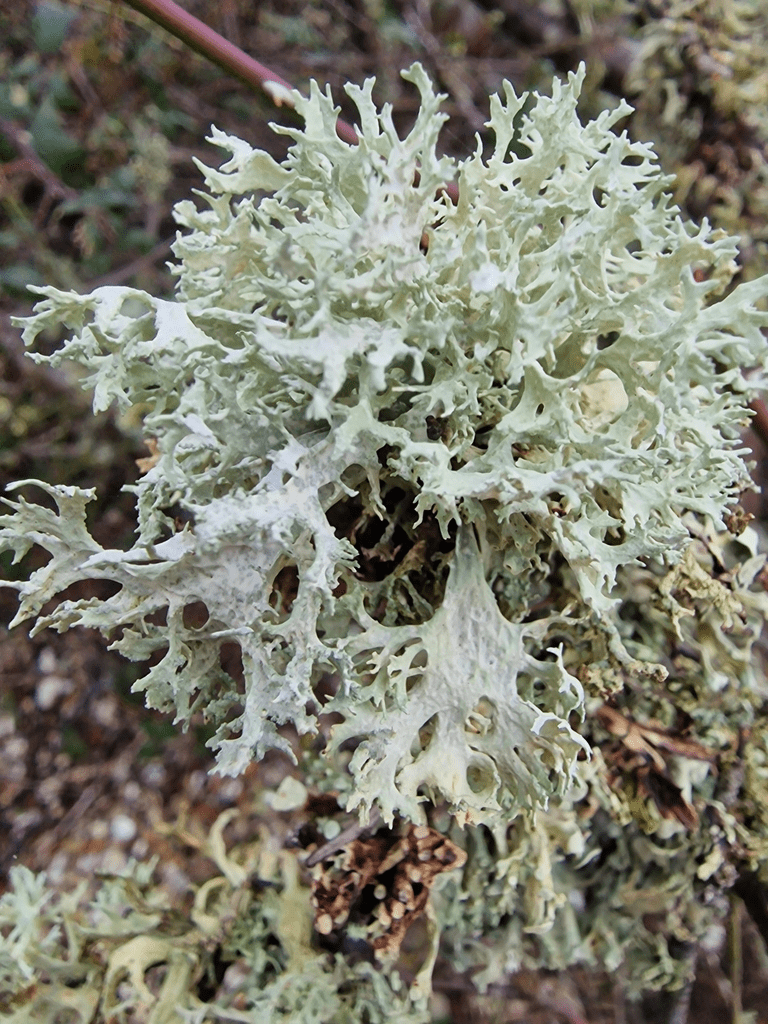

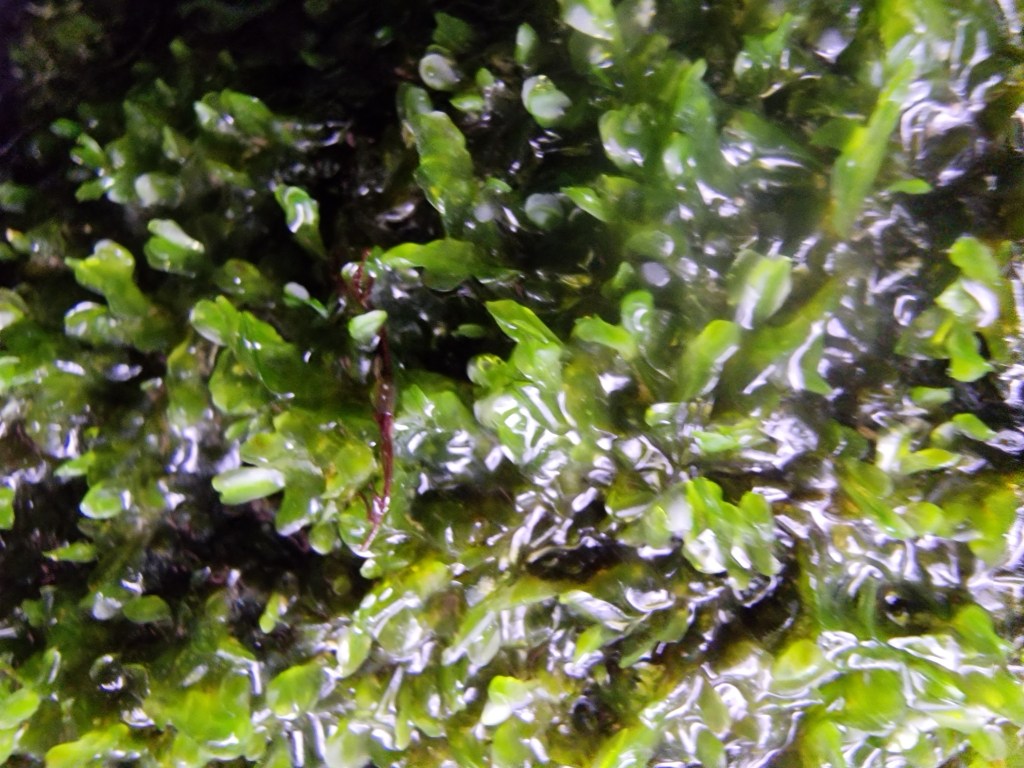

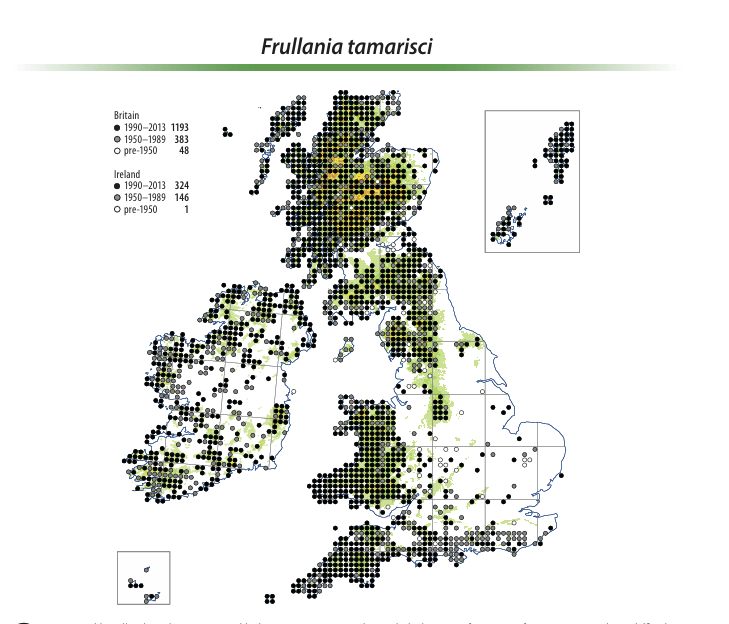

Frullania tamarisci Tamarisk Scalewort

Growing on an Oak.

Frullania dilitata, Dilated Scalewort, is very common epiphytic liverwort in Sussex, and can bee seen on may trees in most landscape types in Sussex.

F tamarisci; it is primarily a liverwort of western Atlantic woodland, and is rare in Sussex. F tamarisci has more “body” and grows slight “out” of the tree; whereas F. dilitata grows flat and is adpressed to the tree trunk.

It is a humidity-demanding species and sheltered valley or ravine woodlands in western areas will often have a substantial population on trees and boulders. It’s usually easily picked out from F. dilatata by its glossiness (when dry) and by the way the shoots grow away from the substrate. BBS Frullania tamarisci

Lophocolea bidentata Bifid Crestwort

This is likely to be the first leafy liverwort you will encounter as a beginner, since it is very common and occurs in almost any habitat. Look at it closely, the first few times you find it as it is very beautiful and has some interesting features. All of the leaves are conspicuously bilobed and of a pale green, translucent hue. The underleaves are large, bilobed and with each lobe itself bearing a side-tooth. BBS Lophocolea bidentata

Lophozia ventricosa Tumid Notchwort

Common in Sussex in High Weald ghylls, but not anywhere else in Sussex

Aery common species wherever acid soil or peaty ground is found, so rare only in the more calcareous lowlands of England and Ireland. BBS Lophozia ventricosa

Male Metzgeria furcata Forked Veilwort

Forked Veilwort is an extremely common epiphytic liverwort in Sussex, and can bee seen on many trees in most landscape types in Sussex.

Metzgeria furcata is dioicous and so plants will either be male or female but not both. Reproductive structures are found in bud-like, highly modified branches that more or less enclose the archegonia (female) or antheridia (male) on the underside of the thallus. Male branches have a costa, which gives them a stripy appearance.

Scapania undulata Water Earwort

Solenostoma gracillimum Crenulated Flapwort

Thalloid Liverworts

Conocephalum conicum sensu lato, Great Scented Liverwort

This, along with Pellia epiphylla, Common Pellia and Pellia endiviifolia, Endive Pellia, are extremely common in Sussex often on the banks of ghylls and streams in the low or high weald

The cone shaped structures are the female archegonia, multicellular structure or organ of the gametophyte phase liverworts of certain producing and containing the ovum (female gamete) The corresponding male organ is called the antheridium. . Archegonia are typically located on the surface of the plant thallus. Conocephalum conicum is complex (aggregate) of various similar species.

Pellia epiphylla, Common Pellia

This is hard to distinguish from Pellia endiviifolia, Endive Pellia; it is easier to distinguish between the two in winter when Endive Pellia had “frilly” edges to its thalli.

Pellia endiviifolia, Endive Pellia

This is a picture of Endive Pellia from Tilgate Forest, not the location visited on 23.03.24; because it clearly shows the frilly thalli.

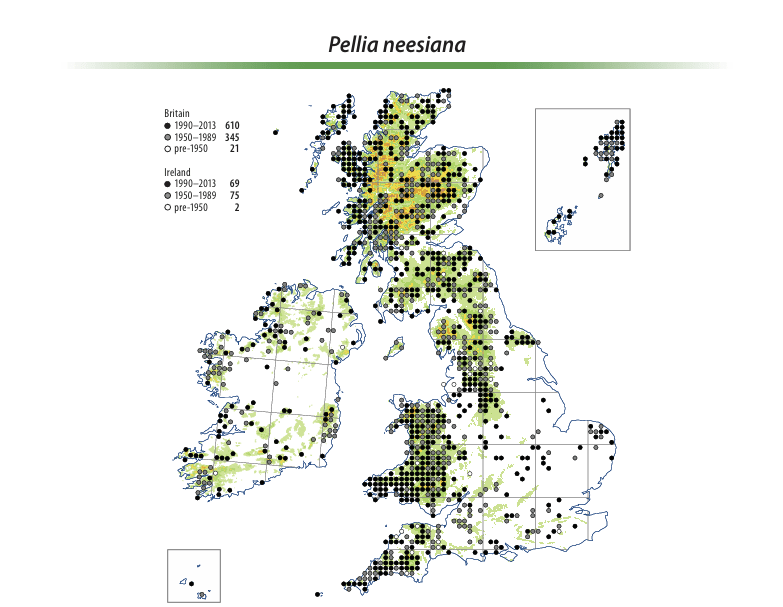

Pellia neesiana Ring Pellia

One of two dioicous species of Pellia – the other is P. endiviifolia – and there is no problem identifying it with confidence when female thalli with more or less untoothed involucral flaps are present, usually in spring.

Male plants are a little more challenging. If antheridial pits extend nearly to the apex of the thallus and there is no involucral flap [after fertilization, the capsule starts to develop and is protected by an involucre] then it is unlikely to be P. epiphylla, our only monoicous species . But how to separate from male P. endiviifolia if the thalli are unbranched? There are two good ways. Firstly, the antheridial pits [antheridia are haploid structure or organ producing and containing male gametes (sperm)] of P. neesiana always look very conspicuous because there are raised, papilliform cells surrounding the pit aperture (see Claire’s excellent close-up images of this feature below). P. endiviifolia does not have these conspicuous cells and so its antheridial pits are less obvious. BBS Pellia neesiana

N.B. Monoecious bryophytes (and other plants) have have both male and female sex organs. Dioecious species have only one (either male or female) sex organ.

Pellia neesiana is much rarer in Sussex that the other Pellia spp. and is predominantly a liverwort of Western Atlantic woodland; it is only found in Sussex in the high weald.