I reached Fredville Park from Brighton by train (4 trains: Brighton to Hamden Park, Hamden Park to Ashford International; Ashford International to Dover Priory, Dover Priory to Snowdown); three and half hours journey time. But it was well worth it; this is an outstanding medival deer park now ornamental parkland.

Originally given to Odo, Bishop of Bayeau and warrior knight, by William of Normandy (King William I, The Conqueror); it has been passed from aristocratic family to aristocratic family. It is still in private ownership. The fact that huge parts of England are still owned by the landed gentry, who inhereited or bought it from Norman Barons who were given land that wasn’t theirs, and they still prohibit the public from much of this land, is a national disgrace.

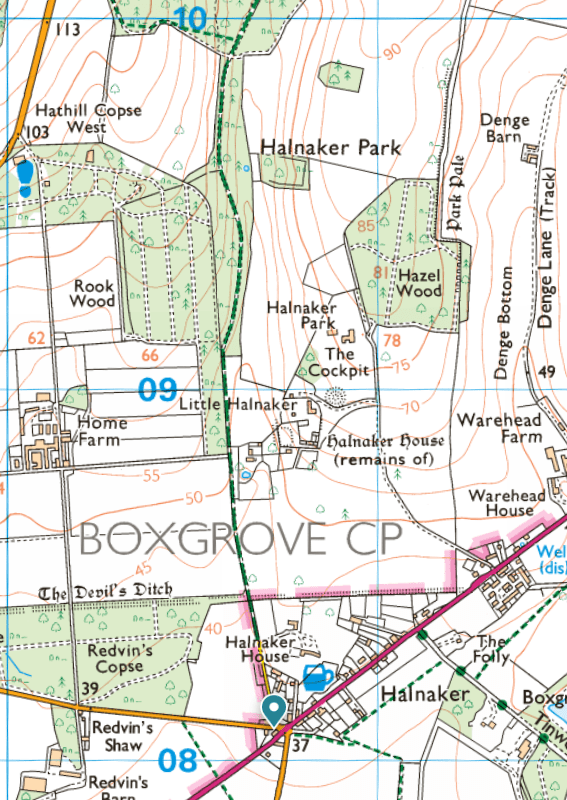

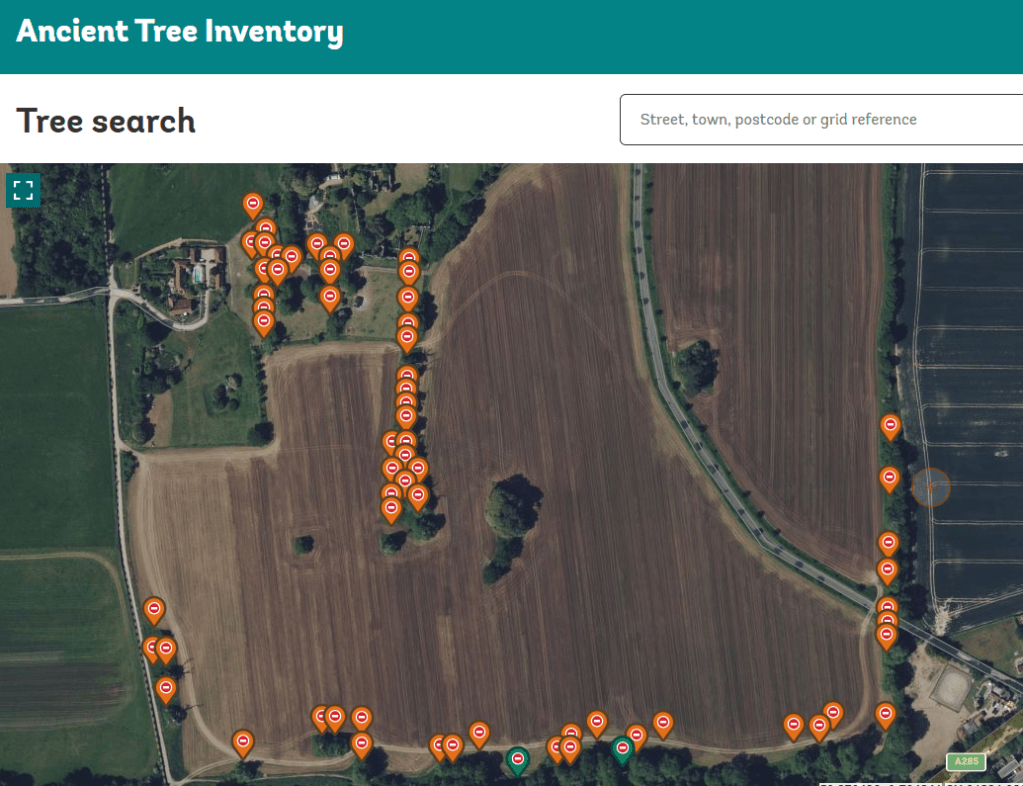

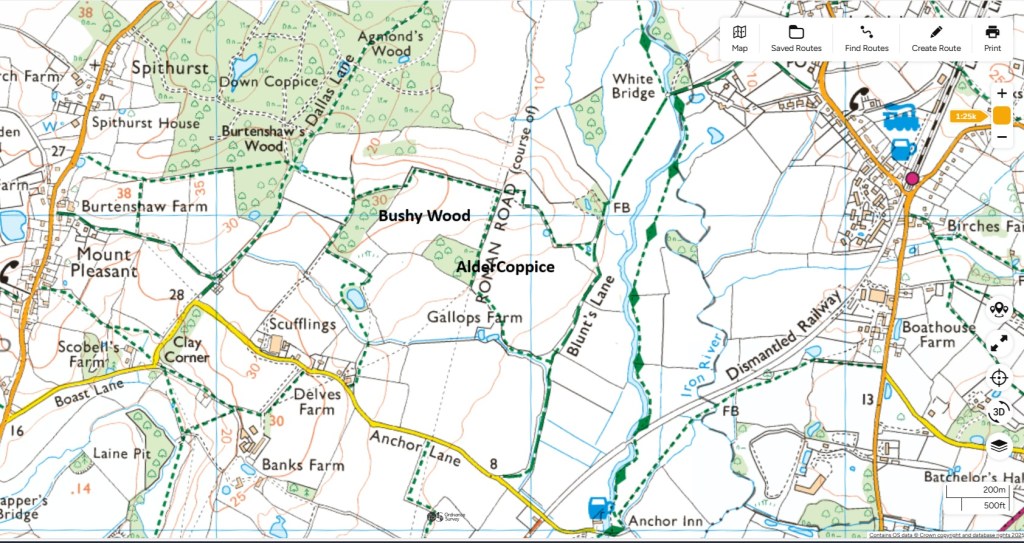

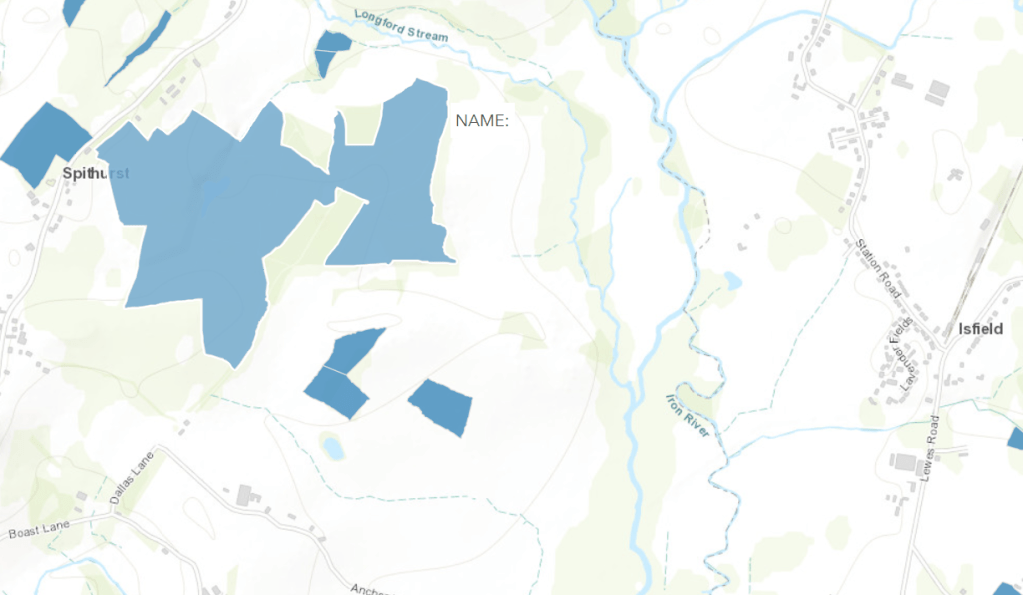

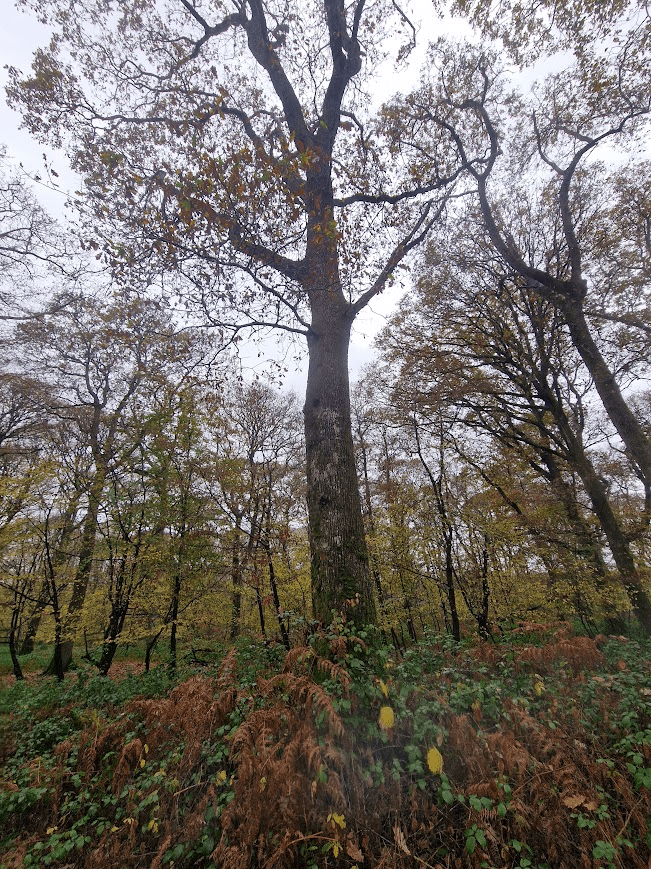

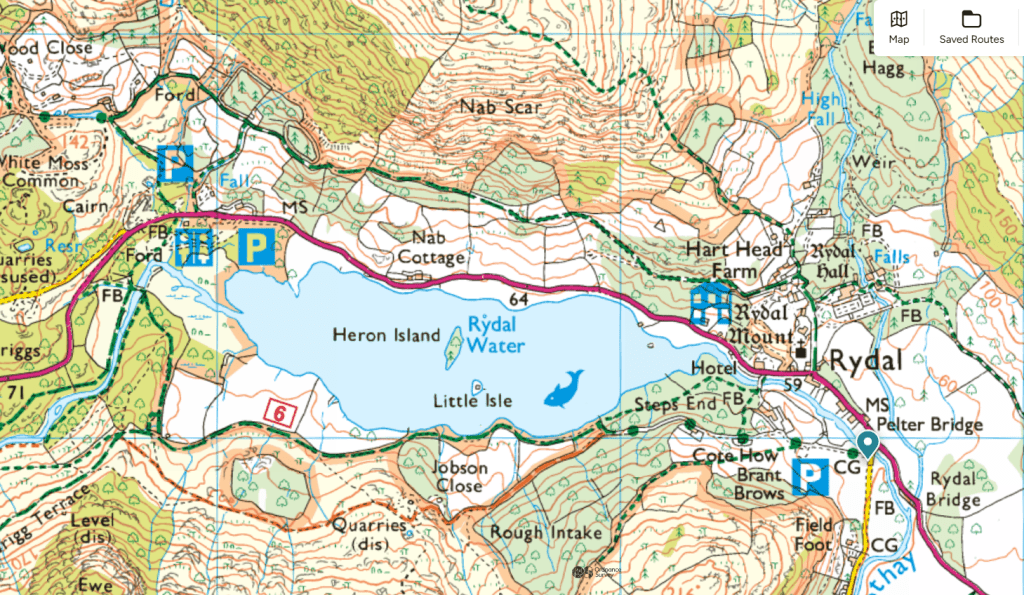

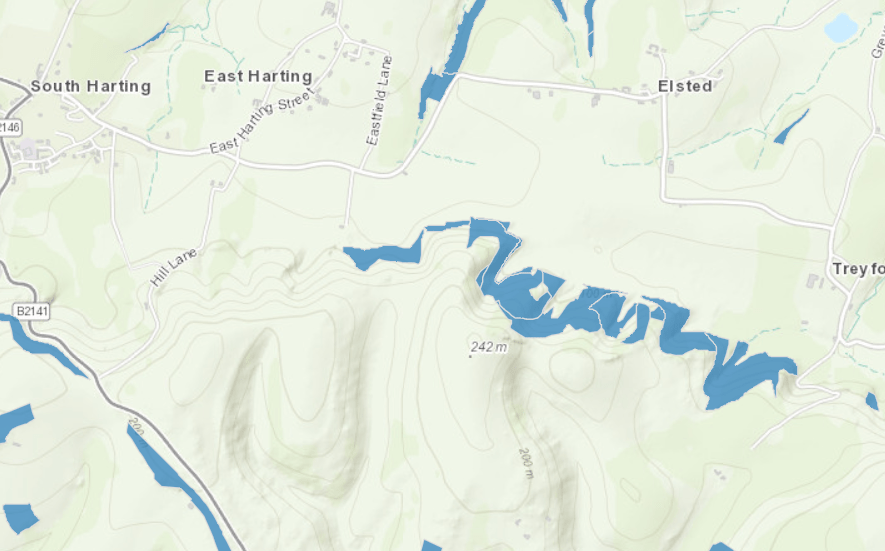

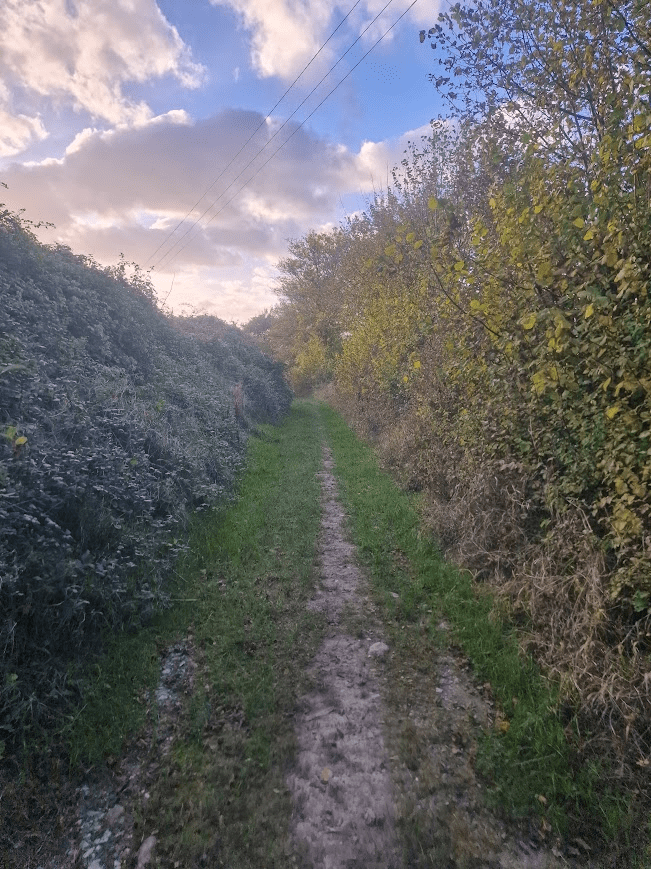

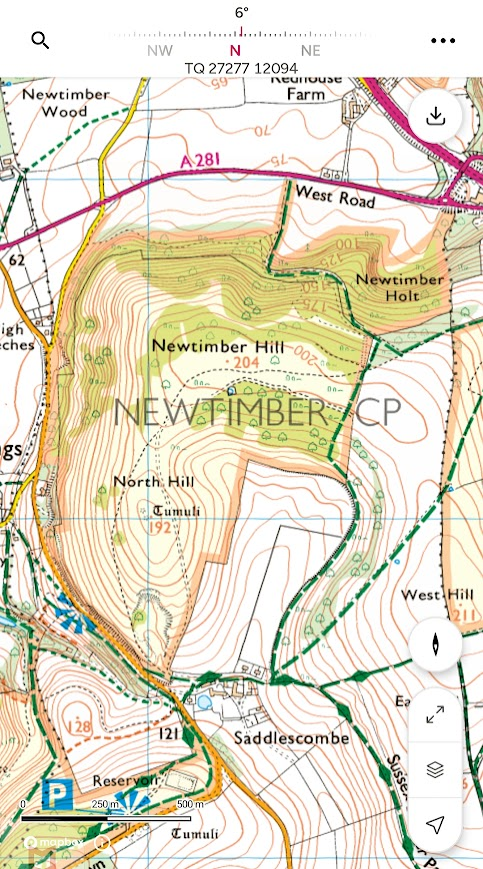

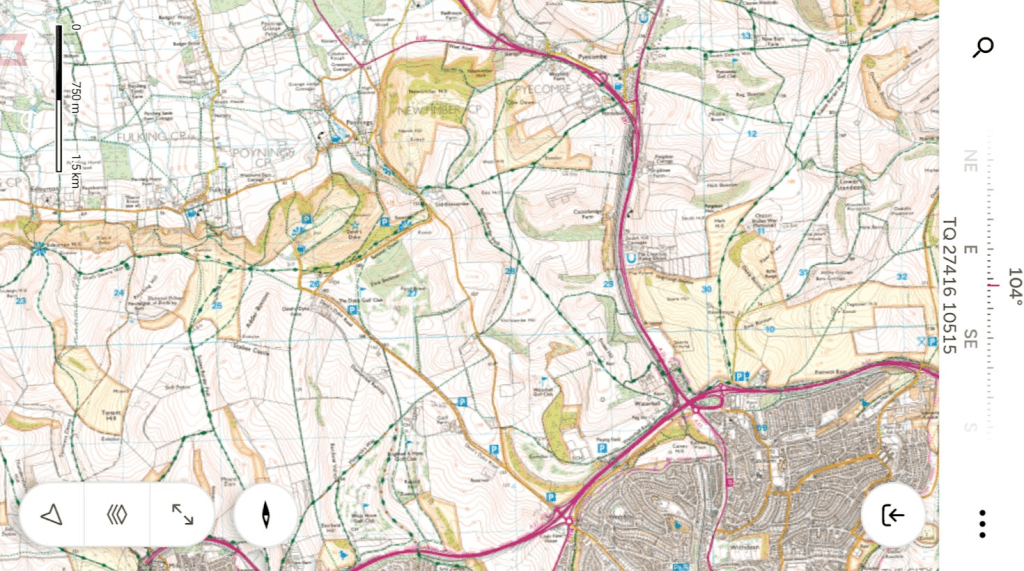

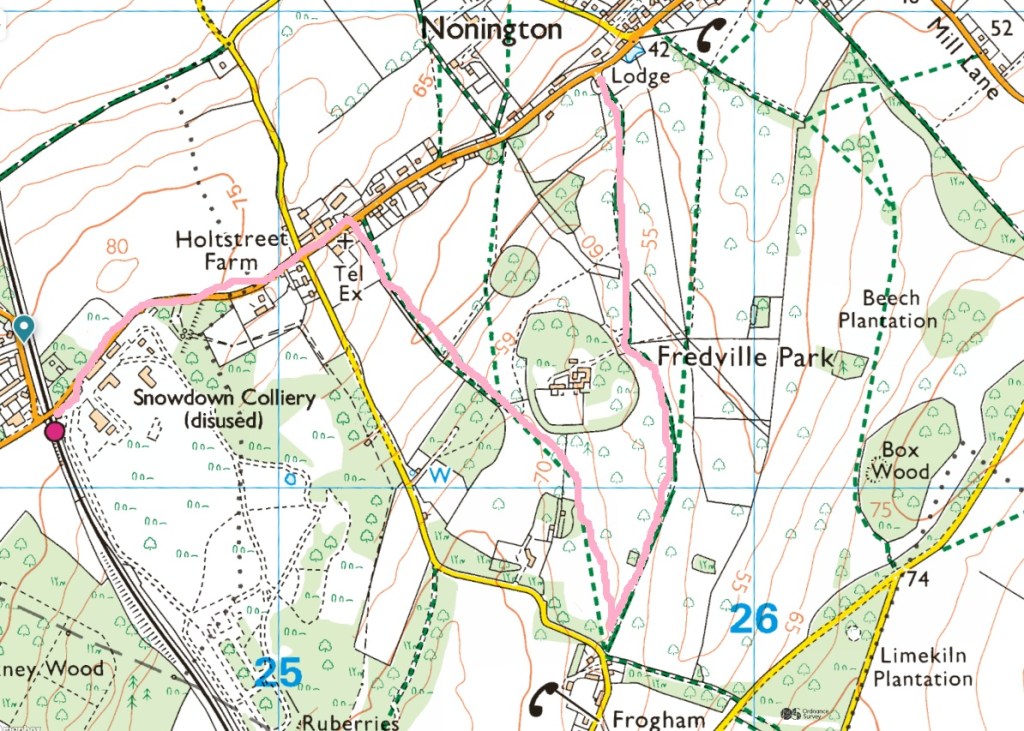

Ordnance Survey Map showing public access to Fredville Park

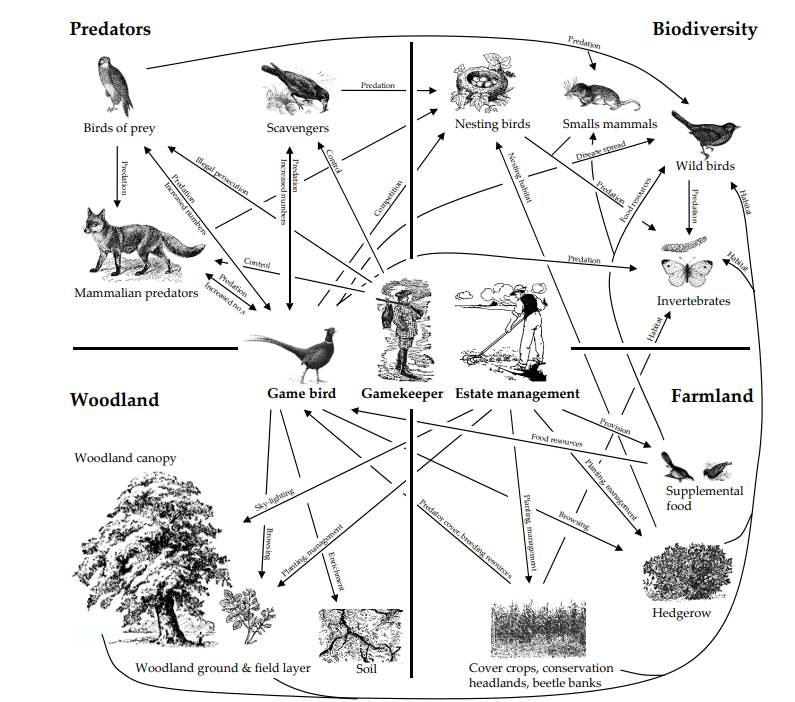

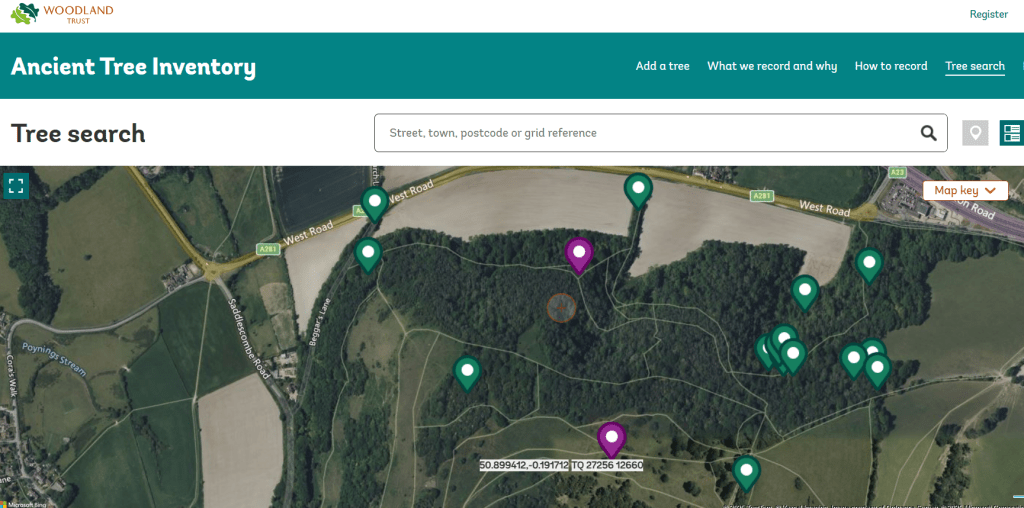

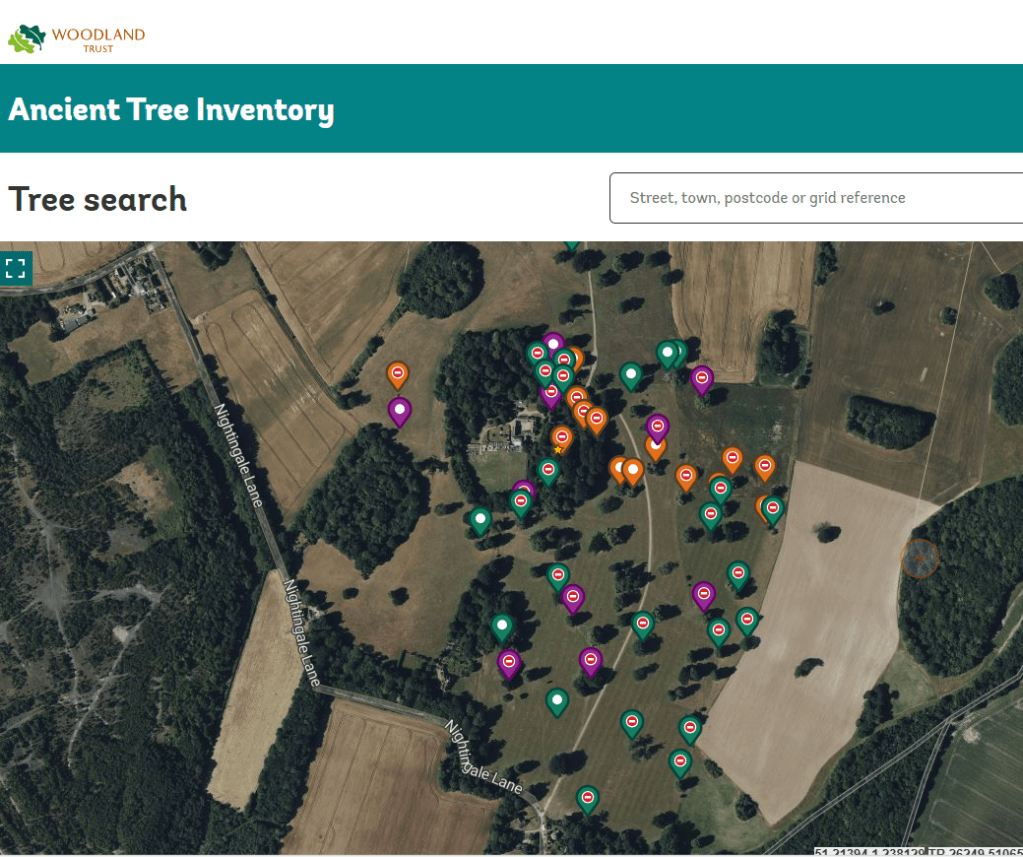

On the Woodland Trust Ancient Tree Inventory map all but the trees next to the footpaths are marked as “no public access” but except for the woodland around Fredville House, which is fenced, I roamed freely off the the paths and got close to many of the trees that the Woodland Trust says has no public access. Toward the end of the afternoon a stream of 4x4s drove up the road into Fredville House. They were a hunting party, of shootists and game keepers (as I had heard shotguns being used all afternoon, close by, but not in Fredville Park); none of them challenged me and I was clearly off the public footpaths.

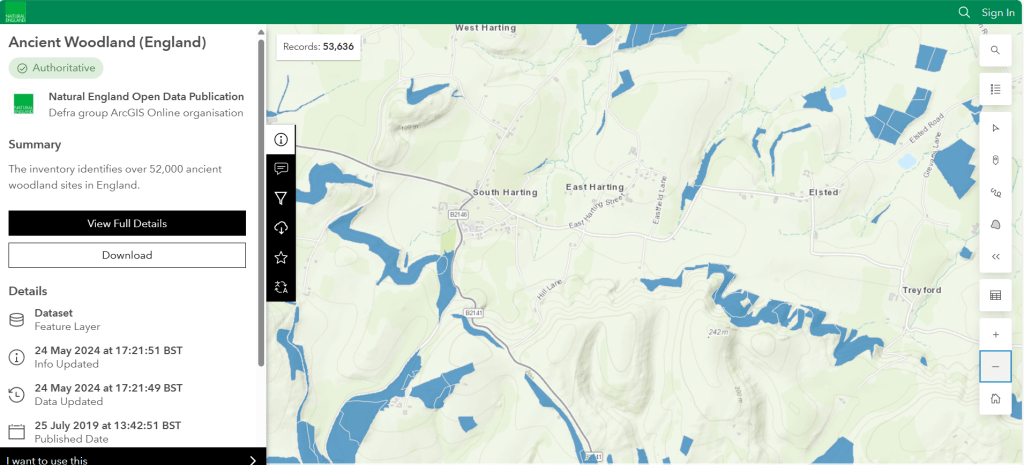

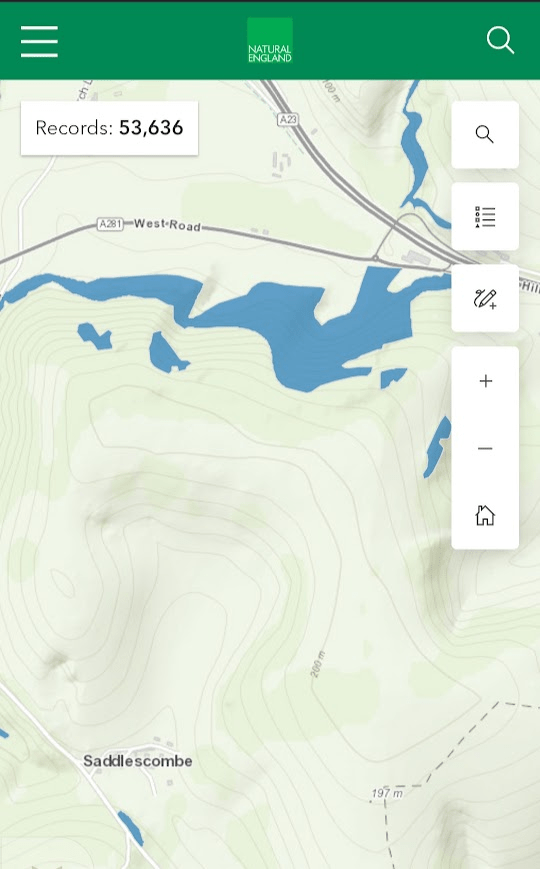

Map from Monumental Trees in Fredville Park

It is not possible to see the three large ancient oak trees, “Majesty”, “Stately”, and ”Beauty”probably 500 years old, including “Majesty” or “The Fredville Oak”, believed to have the largest girth in England, because they are in the fenced of grounds of the former mansion. This is another example of precious natural assets that should be viewable by the public, being shut off to the public.

STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE from The Kent Compendium of Historic Parks and Gardens for Dover Fredville Park (2017) Kent Garden Trust, Dover District Council, and Kent County Council, retrieved 07.12.25 https://www.kentgardenstrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Fredville-Park.pdf

Fredville Park has many parkland trees. ,,, Not far from the former mansion are the remains of a Spanish chestnut avenue, planted at least 250 years ago. Many of these trees are still in very good condition (2017).

The boundary of the C18 pleasure ground enclosure is intact and encompasses

the remaining historic structures including the walled kitchen garden, stables and ice house as well as potential archaeological remains of the mansion. Of particular note, within the immediate grounds of the former mansion, are three large ancient oak trees, probably 500 years old, and a mid-late C19 Wellingtonia. One of these oaks, named “Majesty” or “The Fredville Oak”, is believed to have the largest girth in England.

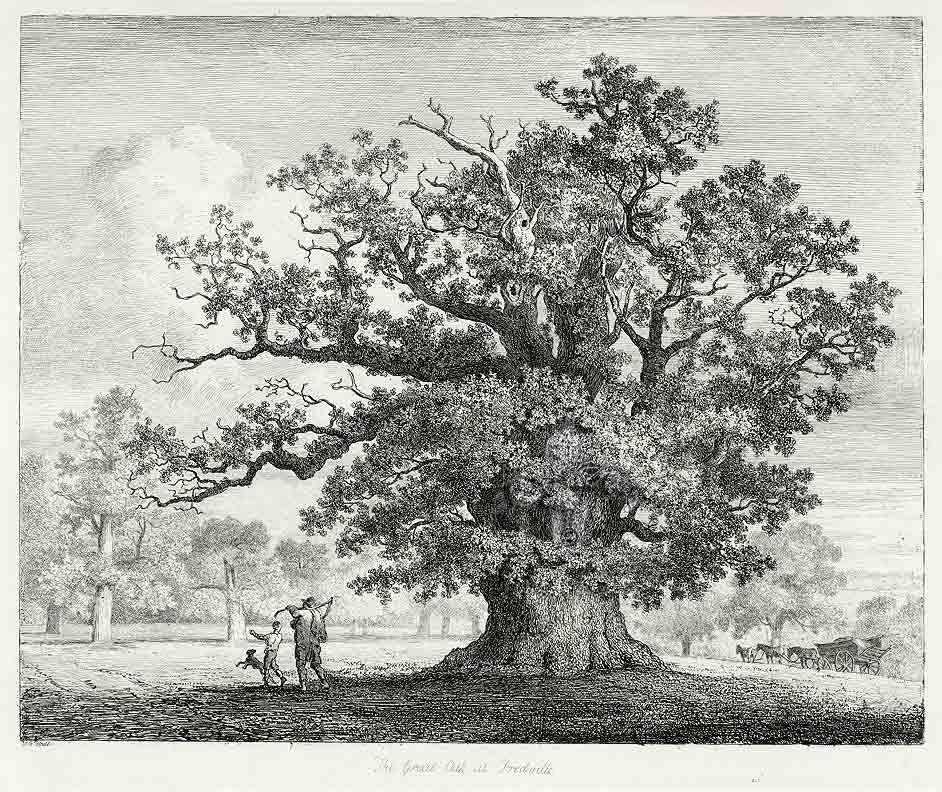

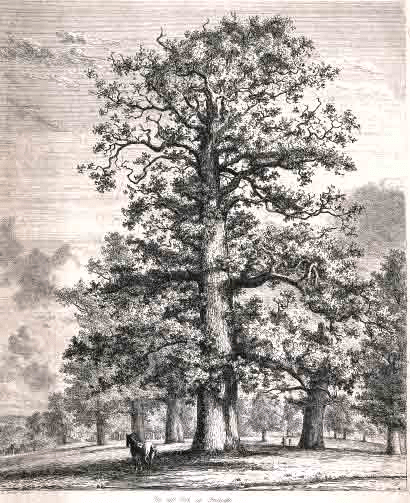

Here are some drawing of these trees from The Old Parish of Nonington – The Fredville Estate – The Trees of Fredville Park. More photos and drawings can be seen atL

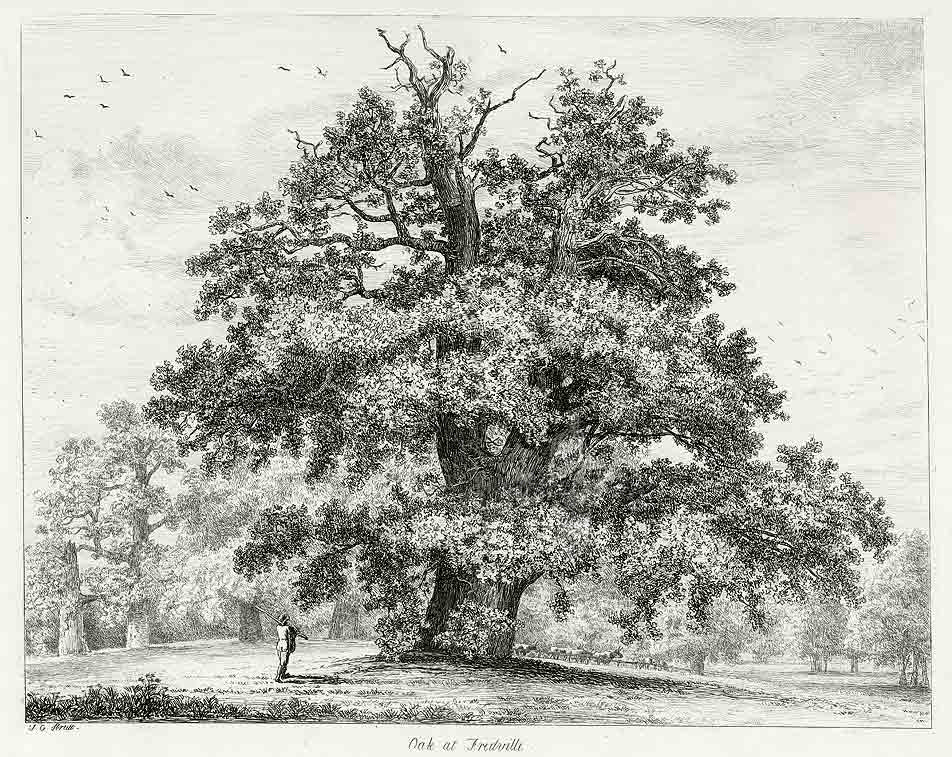

“The Majestie” or Great Oak at Fredville drawn from life by Jacob George Strutt for his Sylva Britannica in 1824 from The Old Parish of Nonington – The Fredville Estate – The Trees of Fredville Park.

A tall oak at Fredville, believed to be “Stately”, drawn from life by Jacob George Strutt for his “Sylva Britannica in 1824 from The Old Parish of Nonington – The Fredville Estate – The Trees of Fredville Park.

Another tall oak at Fredville, believed to be “Beauty”, by Jacob George Strutt for his “Sylva Britannica in 1824 from The Old Parish of Nonington – The Fredville Estate – The Trees of Fredville Park.

The history of the estate:

CHRONOLOGY OF THE HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT from The Kent Compendium of Historic Parks and Gardens for Dover Fredville Park (2017) Kent Garden Trust, Dover District Council, and Kent County Council, retrieved 07.12.25 https://www.kentgardenstrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Fredville-Park.pdf

The origin of the name “Fredville” is not known for certain. Traditionally it is believed to be derived from the Old French: freide ville, meaning a cold place, vecause of its cold, wet, low position. It could, however, be derived from the Old English: frith, meaning the outskirts of a wooded area, plus vill, meaning a manor or settlement, giving “a manor next to the wooded area”.

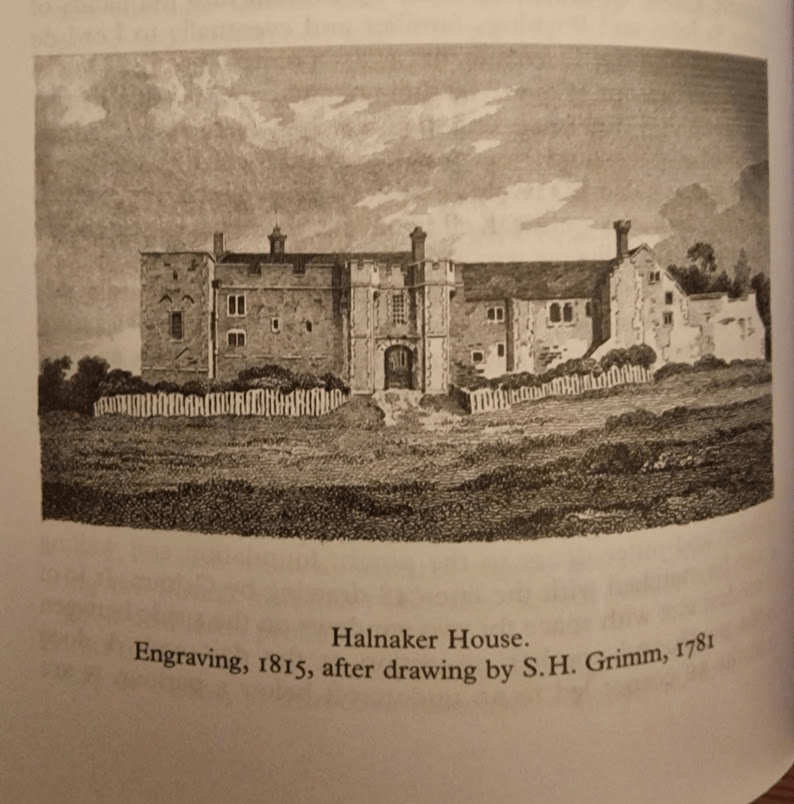

Fredville House and park was originally part of Essewelle Manor. It is recorded in Domesday that in the time of Edward the Confessor it was held by a woman, Molleve, but in 1086 it was held by Ralph de Courbepine from Bishop Odo. De Courbepine’s holdings passed to the Maminot family and in the late 1100’s to the Barony de Saye. By 1250 Essewelle had been divided into Esol and Freydevill. The spelling varied over the centuries: Frydewill (1338), Fredeule (1396),

Fredevyle (1407), Froydevyle (1430), ffredvile (1738).

Hasted lists the families who held Fredville from the Colkins, in the reign of Edward I, to the Boys, in the reign of Richard III. William Boys’ descendant, Major Boys, had many of his estates confiscated for being a Royalist, but Fredville remained in the Boys family until two of his sons sold it to Denzill, Lord Holles in 1673 in order to pay debts. In 1745, Thomas Holles sold it to Margaret, sister of Sir Brook Bridges, baronet of Goodnestone, which is nearby. Margaret Bridges married John Plumptre, a wool merchant of Nottinghamshire, in 1750, but they had no children. The estate passed to John Plumptre through the marriage. Margaret died in 1756 and her husband remarried in 1758 and had a son. John Plumptre rebuilt the manor as a Georgian house. Sir Brook Bridges’ daughter, Elizabeth, married the author Jane Austen’s brother, Edward.

Jane Austen’s letters (1796-1814) show that she was a regular visitor to the Bridges’ estate at Goodnestone and later to Edward’s new home at Godmersham. She was well acquainted with the Plumptres of nearby Fredville (Jane Austen letters to her sister Cassandra, September – October 1813 and March 1814). John Pemberton Plumptre was for a time a suitor of Jane’s niece Fanny. Jane Austen wrote “Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without Affection; and if his deficiencies of Manner &c &c strike you more than all his good qualities, if you continue to think strongly of them, give him up at once.” (Jane Austen letter to Fanny November 1814).

Fanny rejected John Pemberton. In the late 19th century the house was greatly enlarged, its 50 bedrooms accommodating the family of 11 children and the necessary staff. In 1921 Henry Western Plumptre built the much smaller “Little Fredville” nearby in the park as the family home and Fredville mansion was abandoned. It was requisitioned during WWII and occupied by a Canadian tank regiment. A fire destroyed most of the house in 1942 and after the war J H Plumptre, son of Henry Western, decided to demolish the building. Only the clock tower and some converted outbuildings now stand. The site remains in private ownership.

The visible trees of Fredville Park in the order that I saw them:

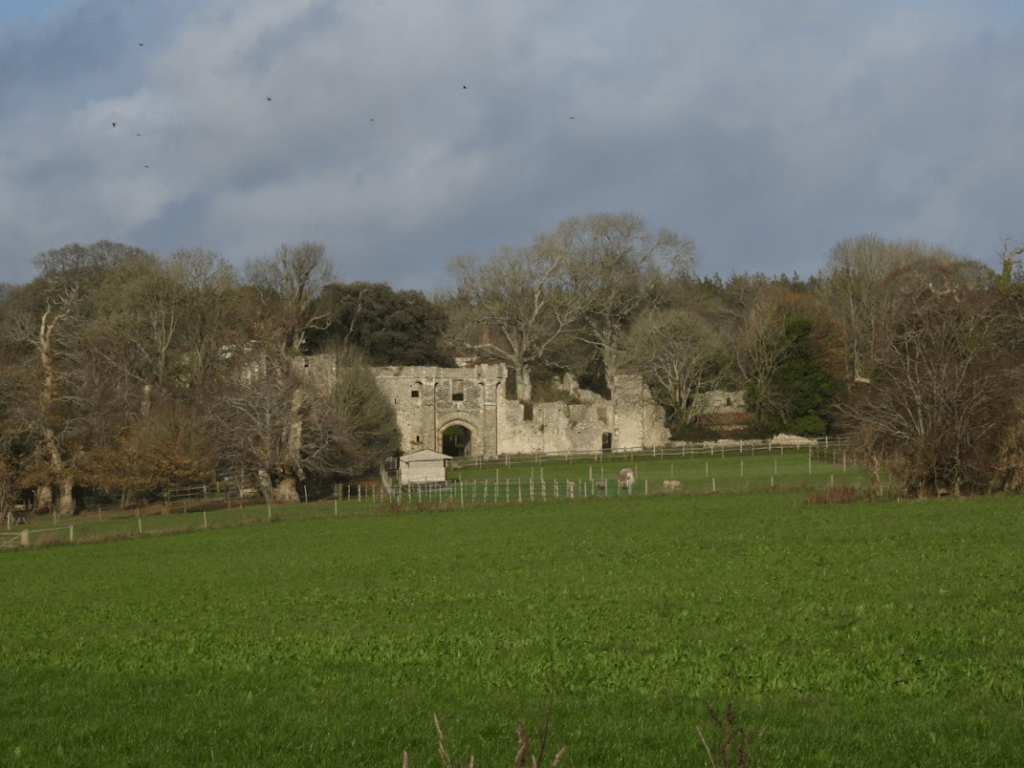

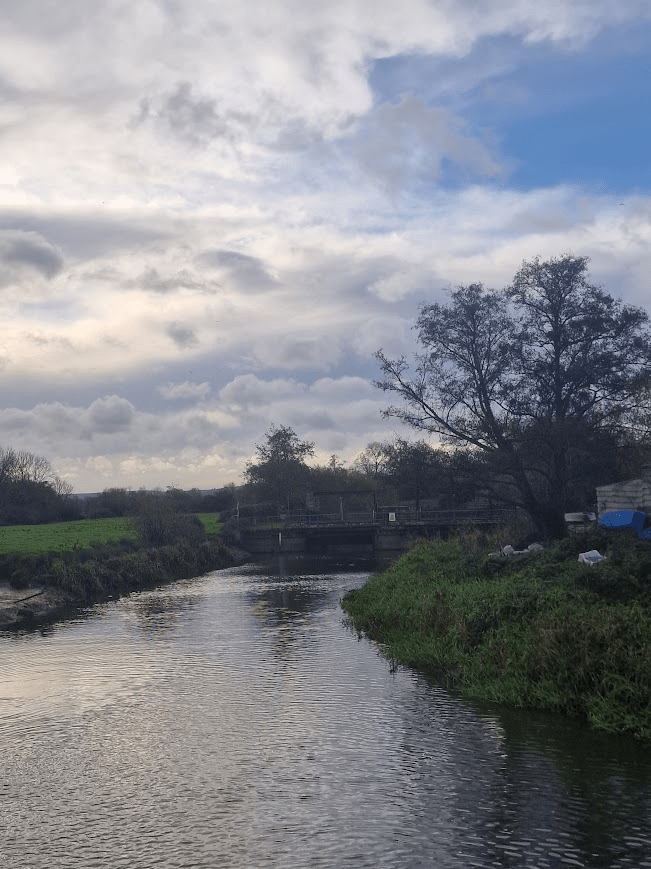

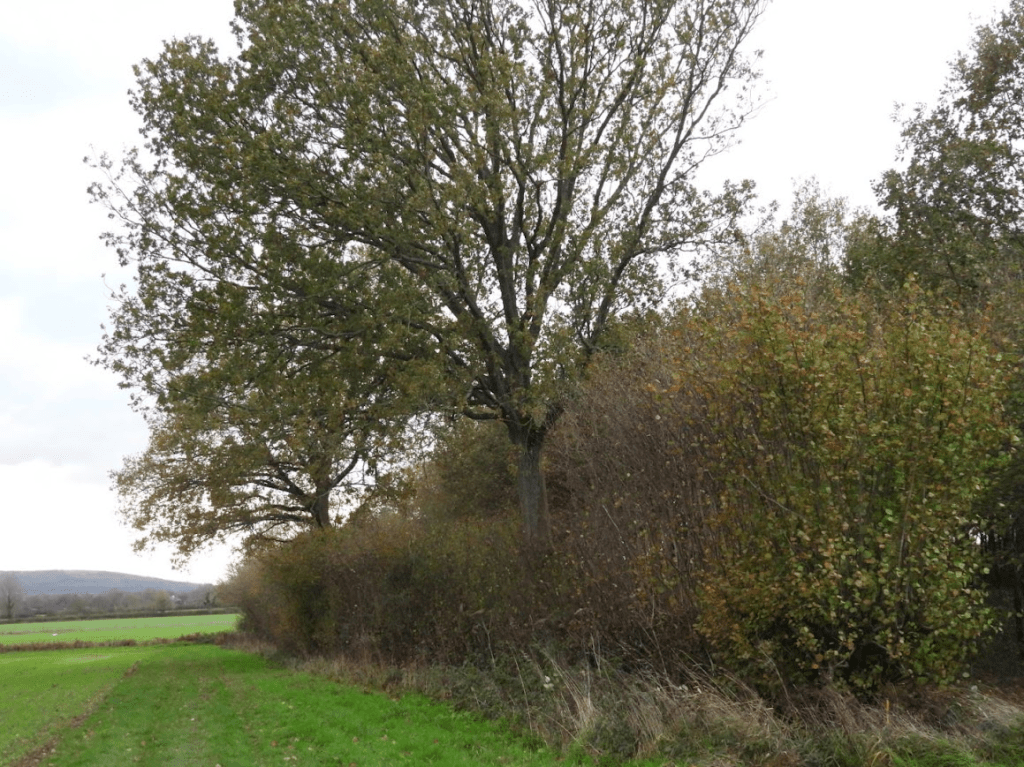

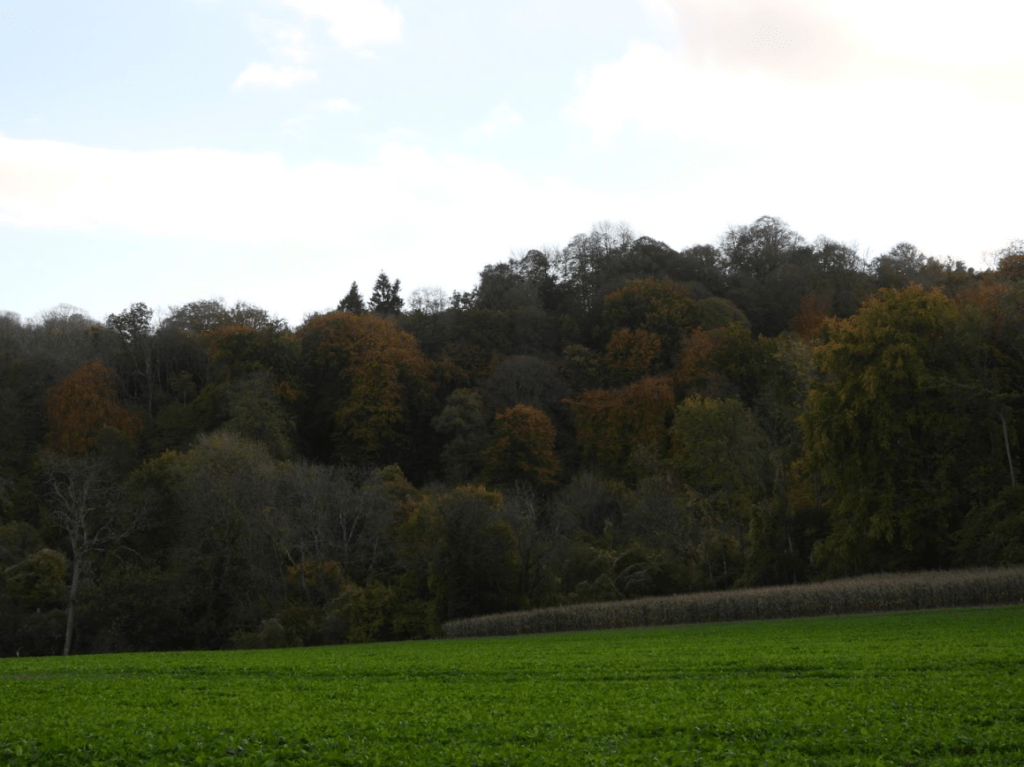

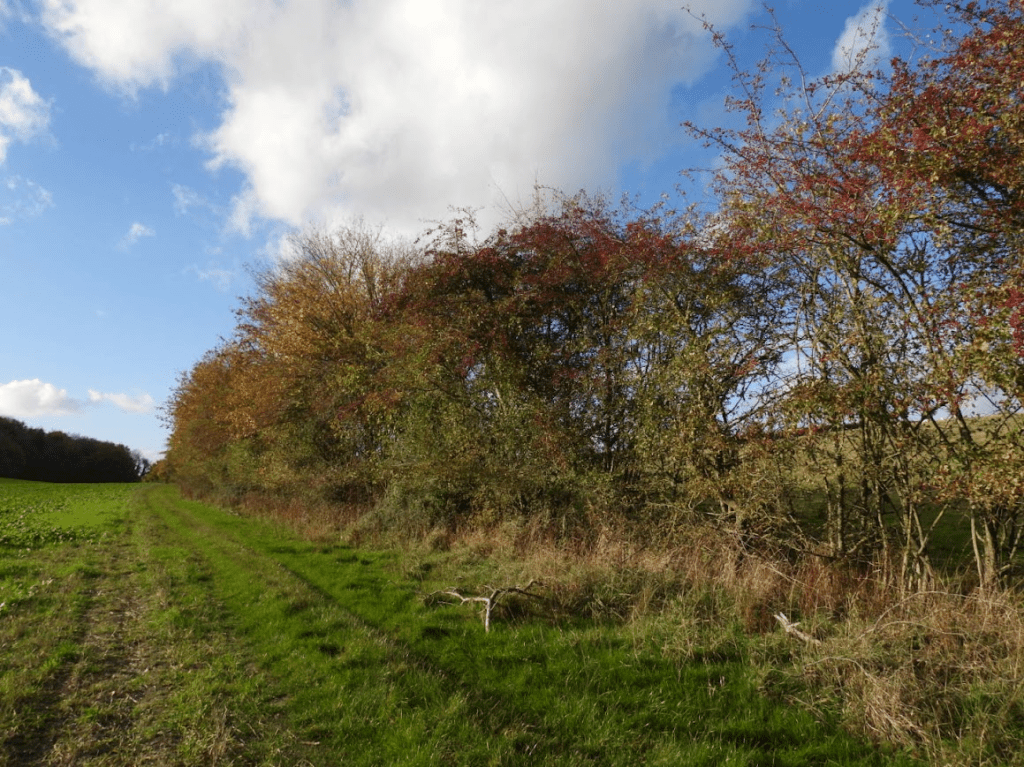

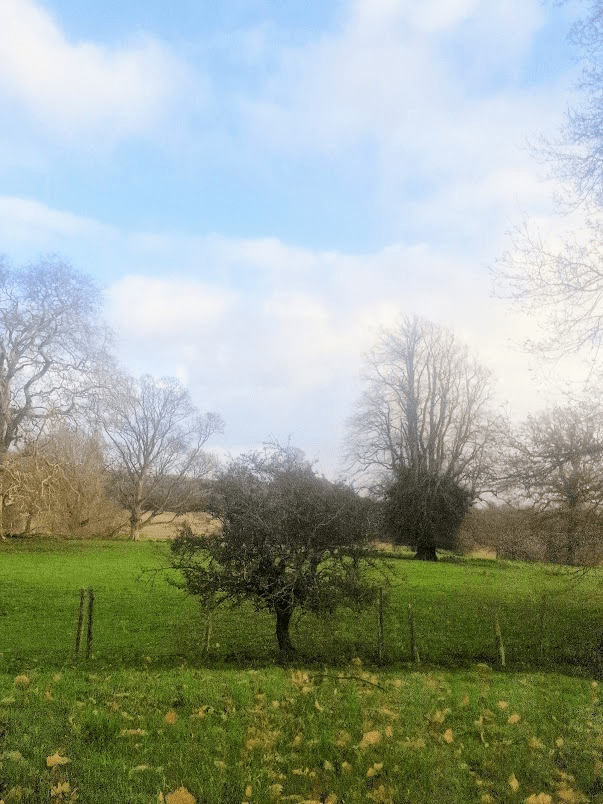

The parkland west of the wood surrounding Fredville House from outside the park

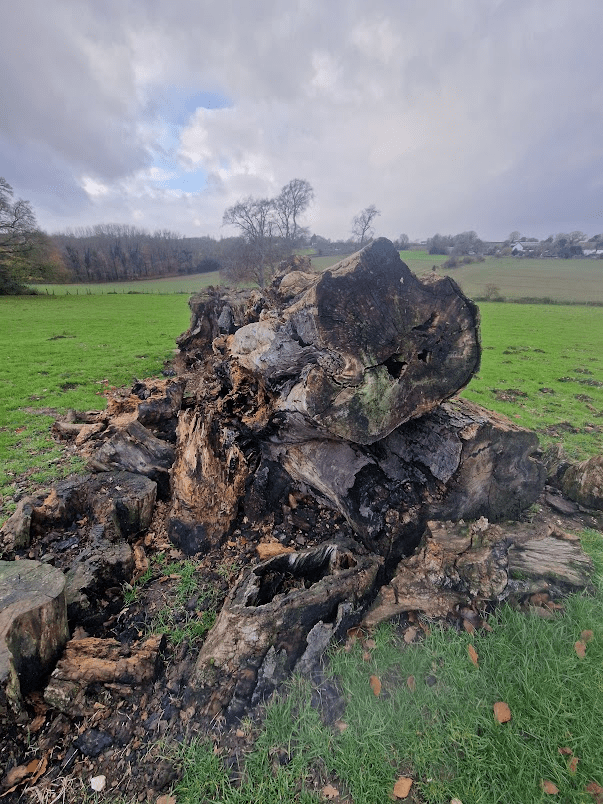

Roots and lower trunk of a felled Pedunculate Oak

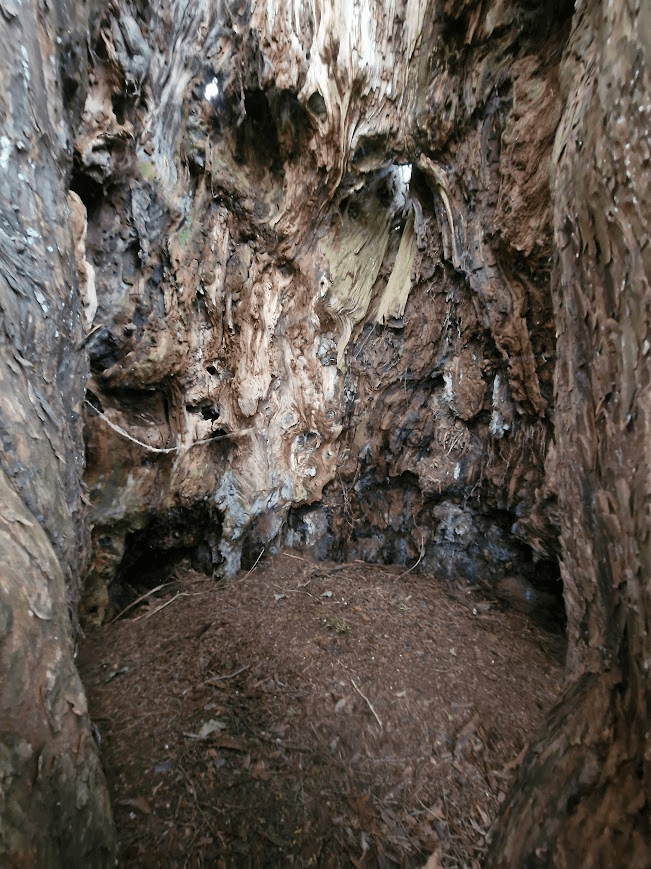

Rotting felled Pedunculate Oak

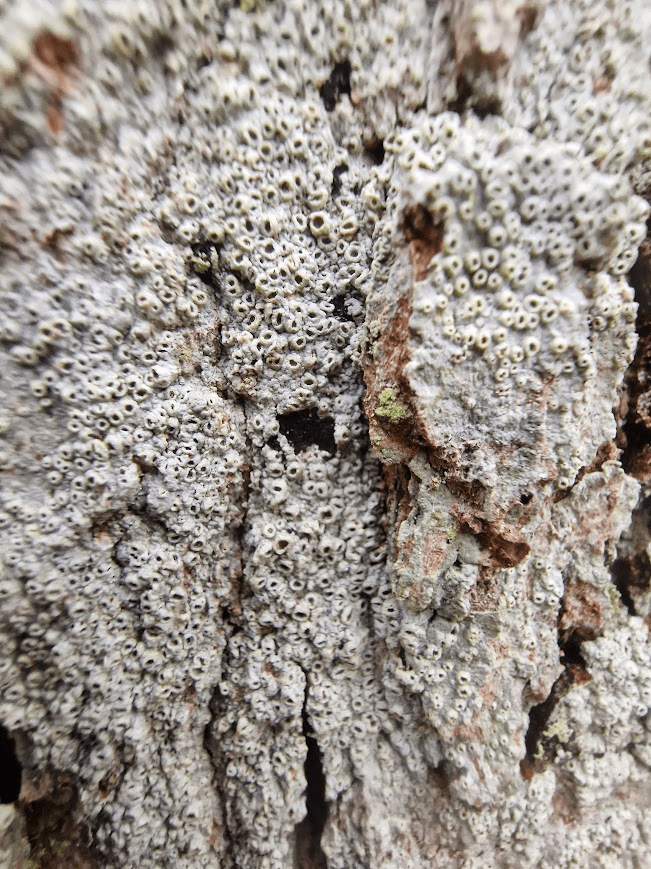

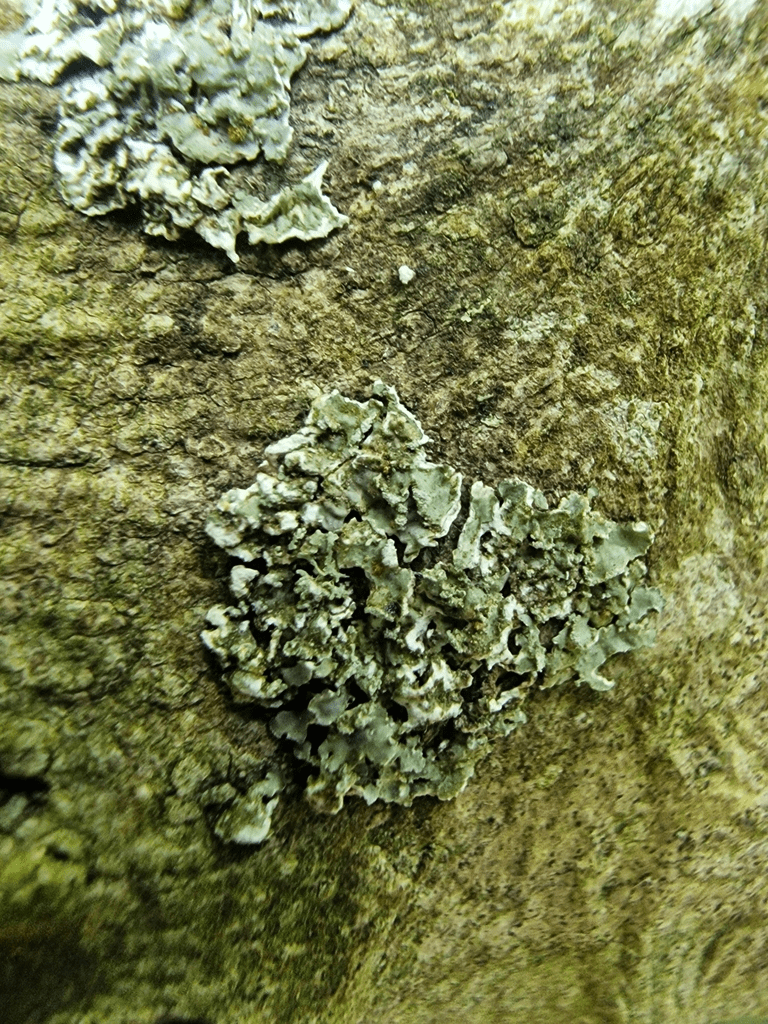

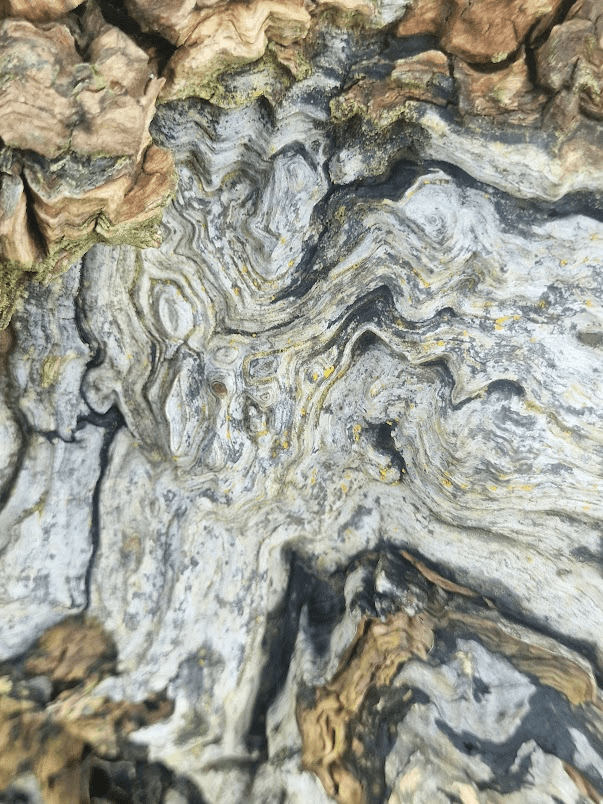

Texture of its bark

Fallen chestnut

With deliquesced Chicken of the Woods, Laetiporous sulphureus

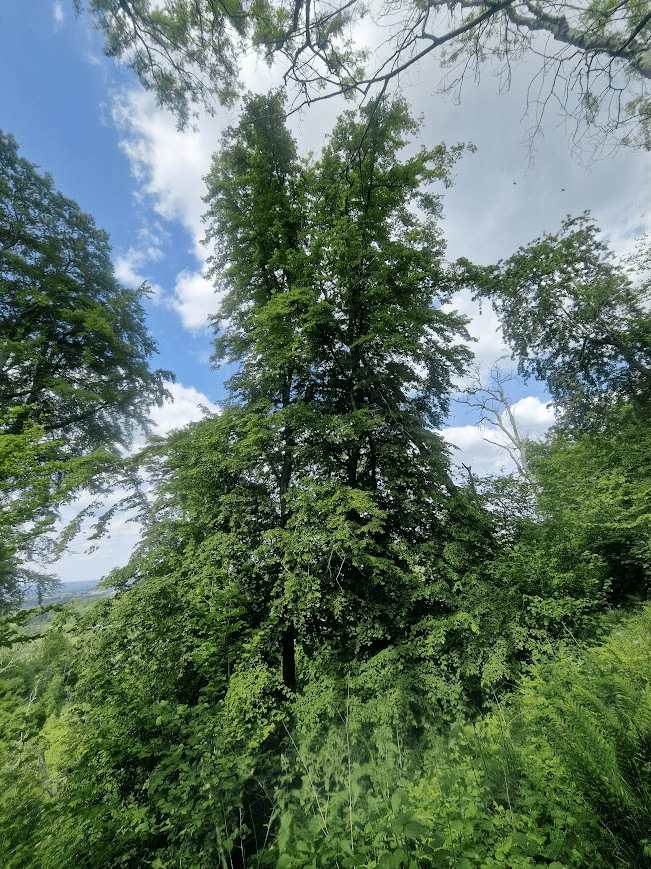

An ancient Beech

Notable Oriental Plane

Fallen Pedunculate Oak

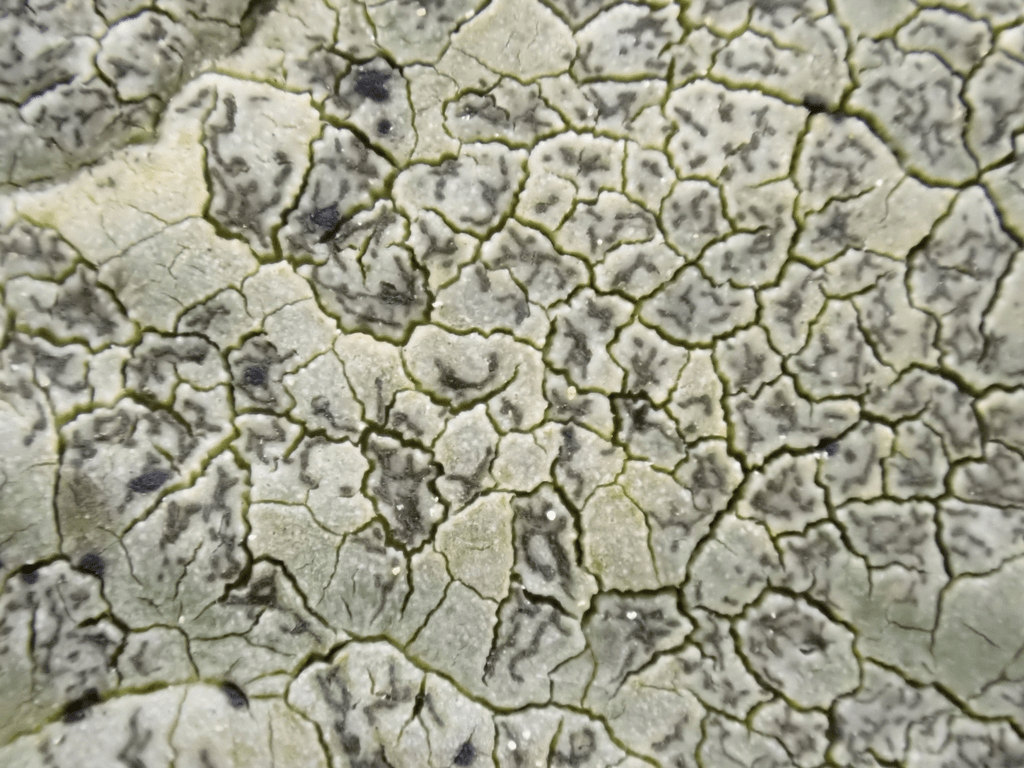

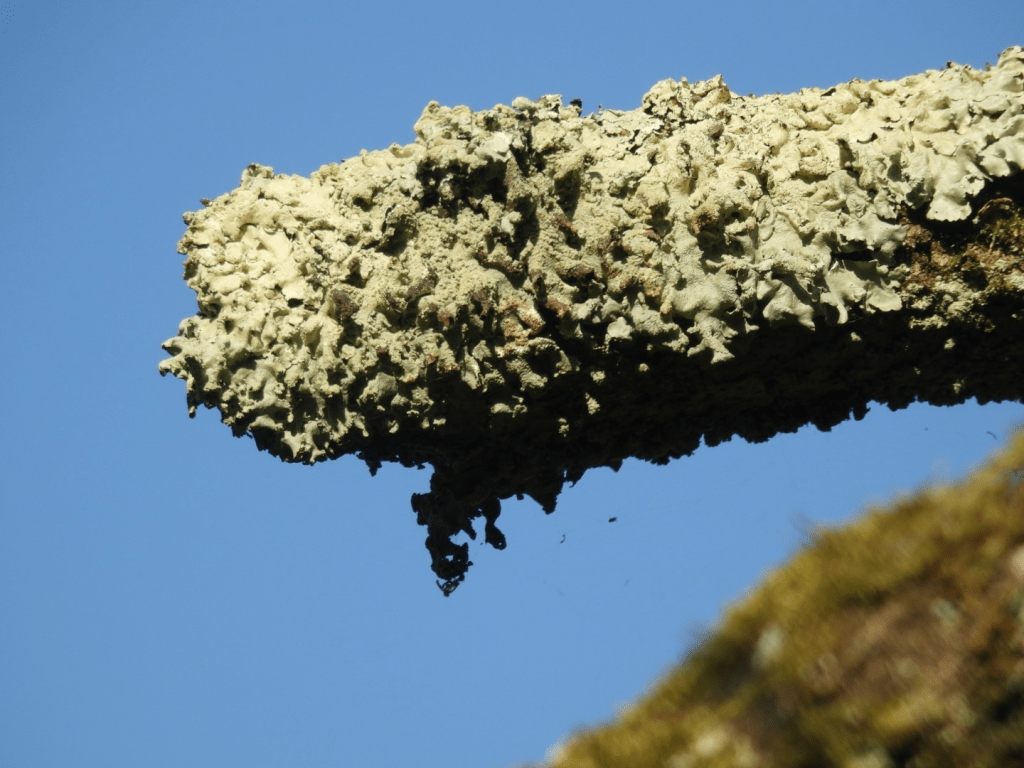

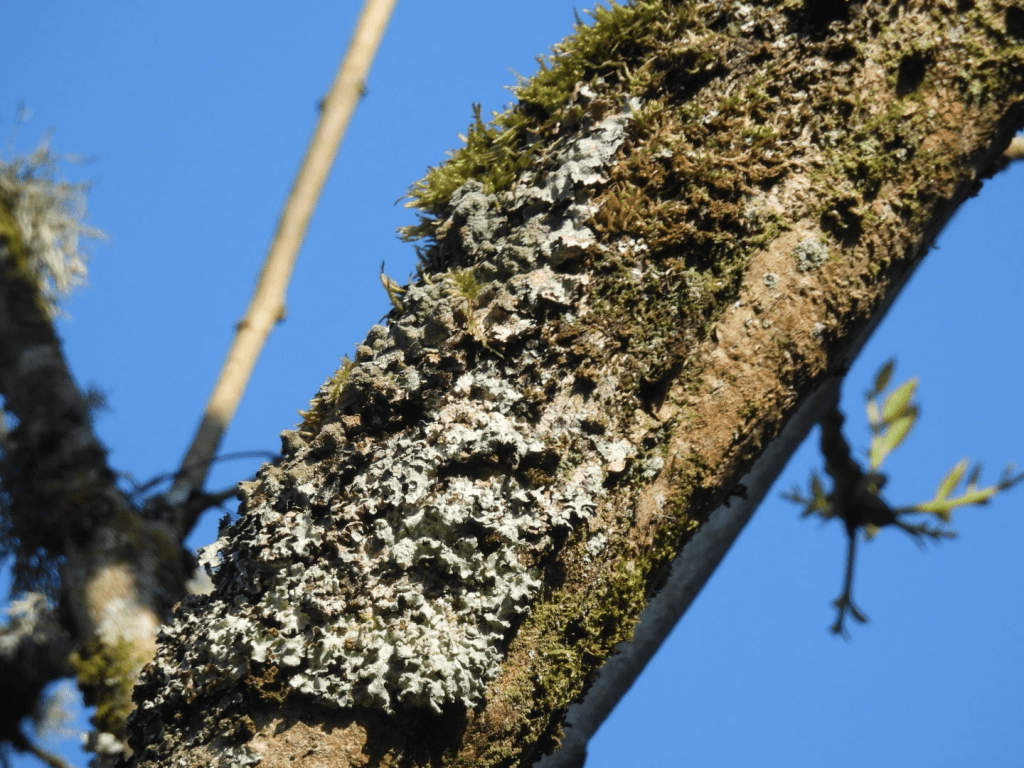

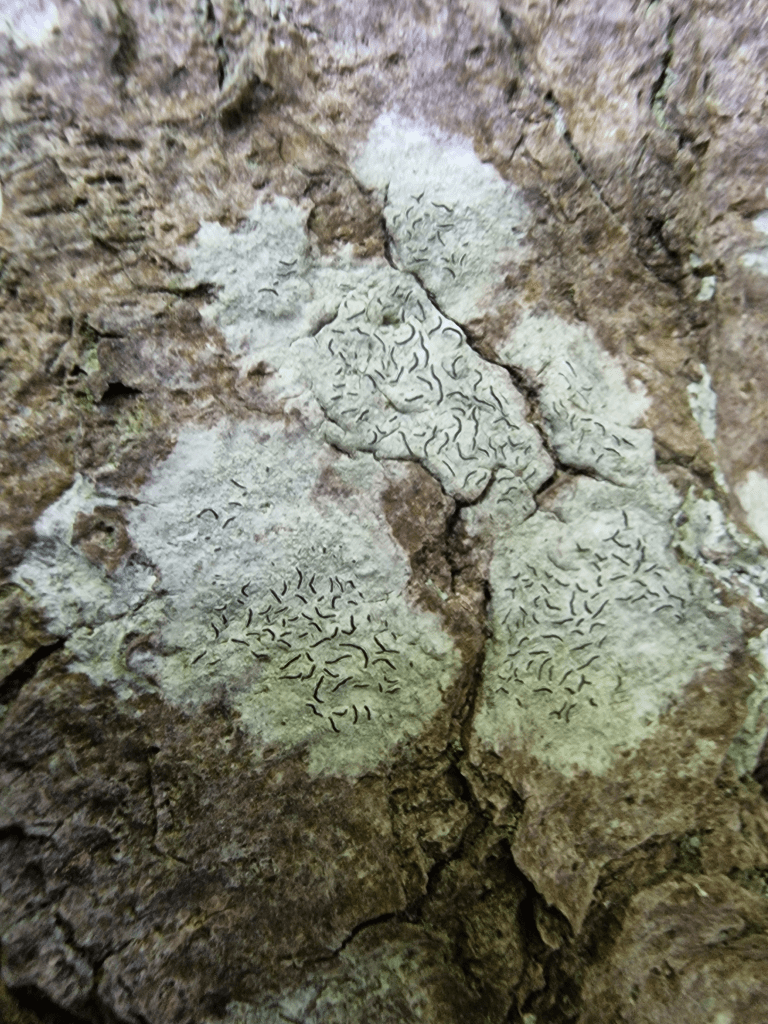

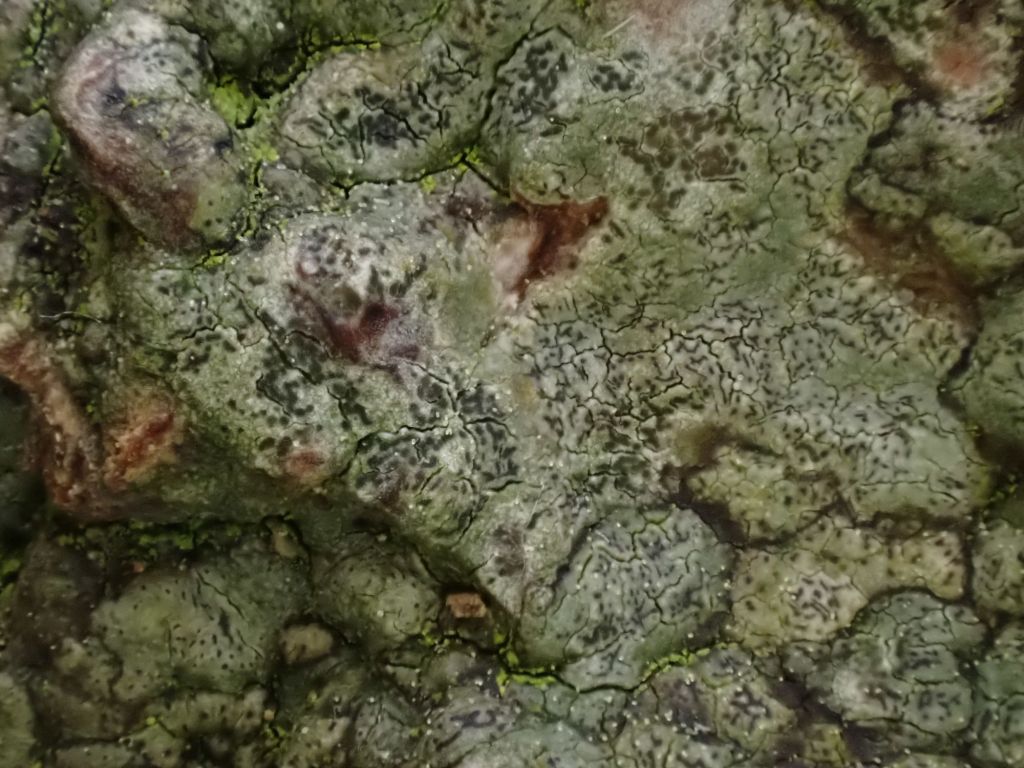

The fungus Hypholoma fasciculare and the mosses Ptychostomum capillare and Grimmia pulvinata, and unidentified lichens, on this tree’s decorticated trunk

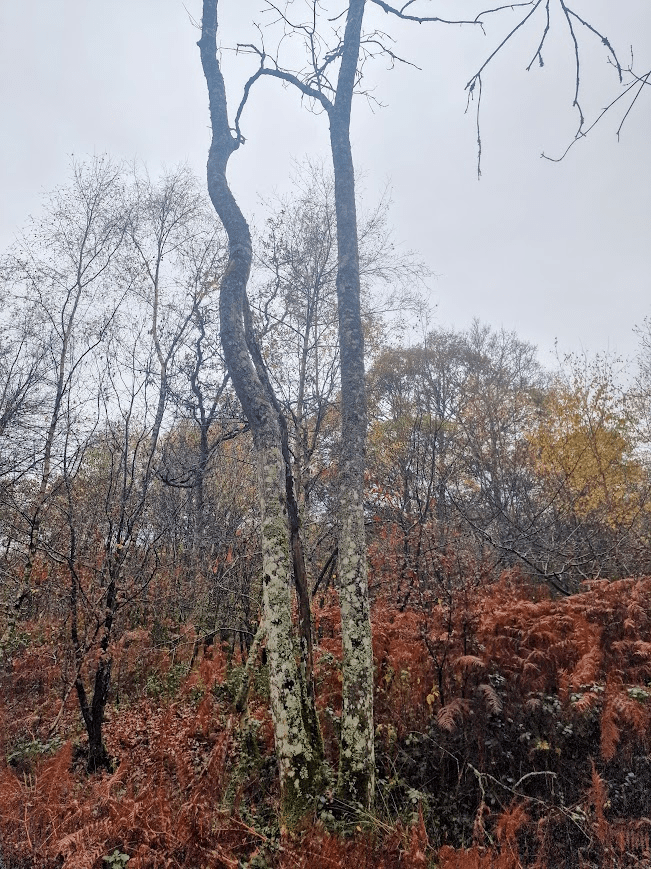

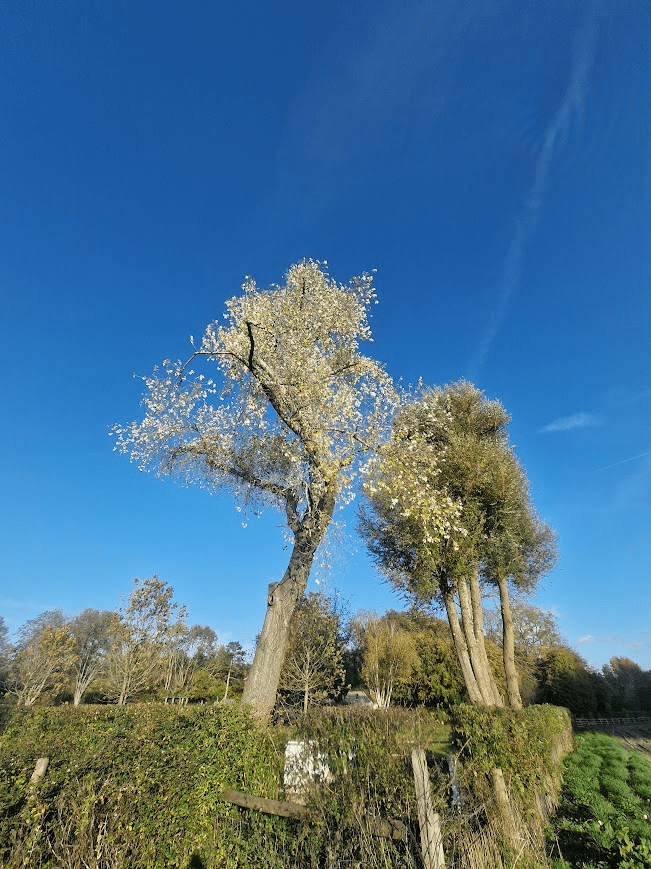

Yew, London Plane and Pedunculate Oak

Oriental Plane

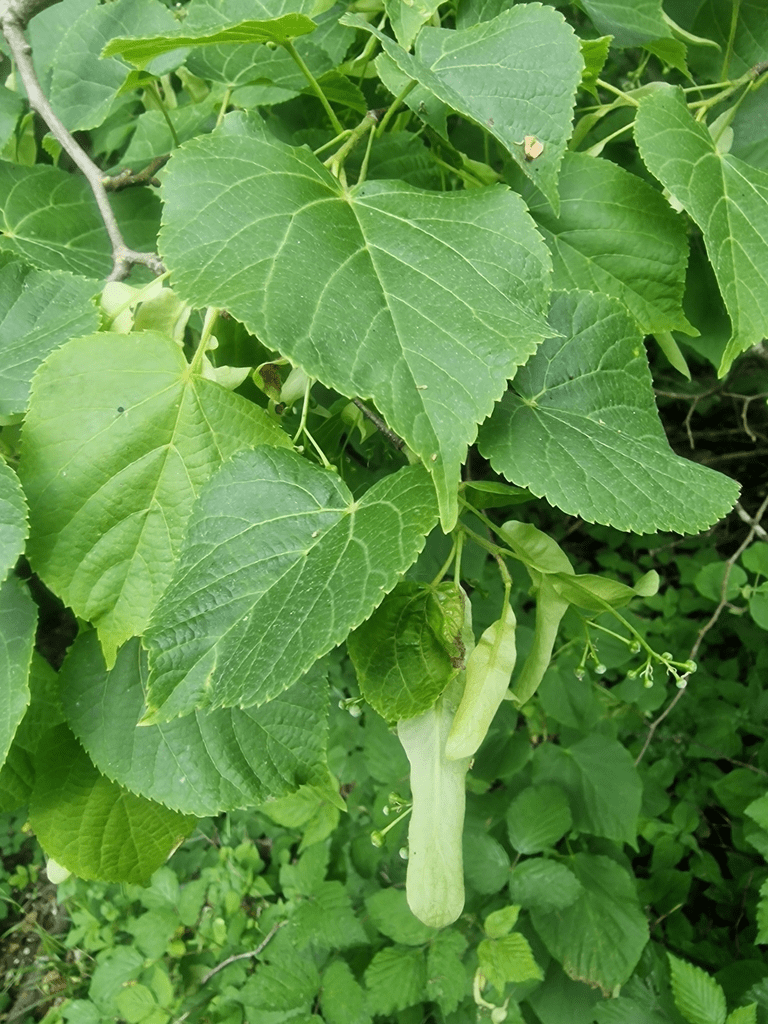

Fruit and leaf of Oriental Plane

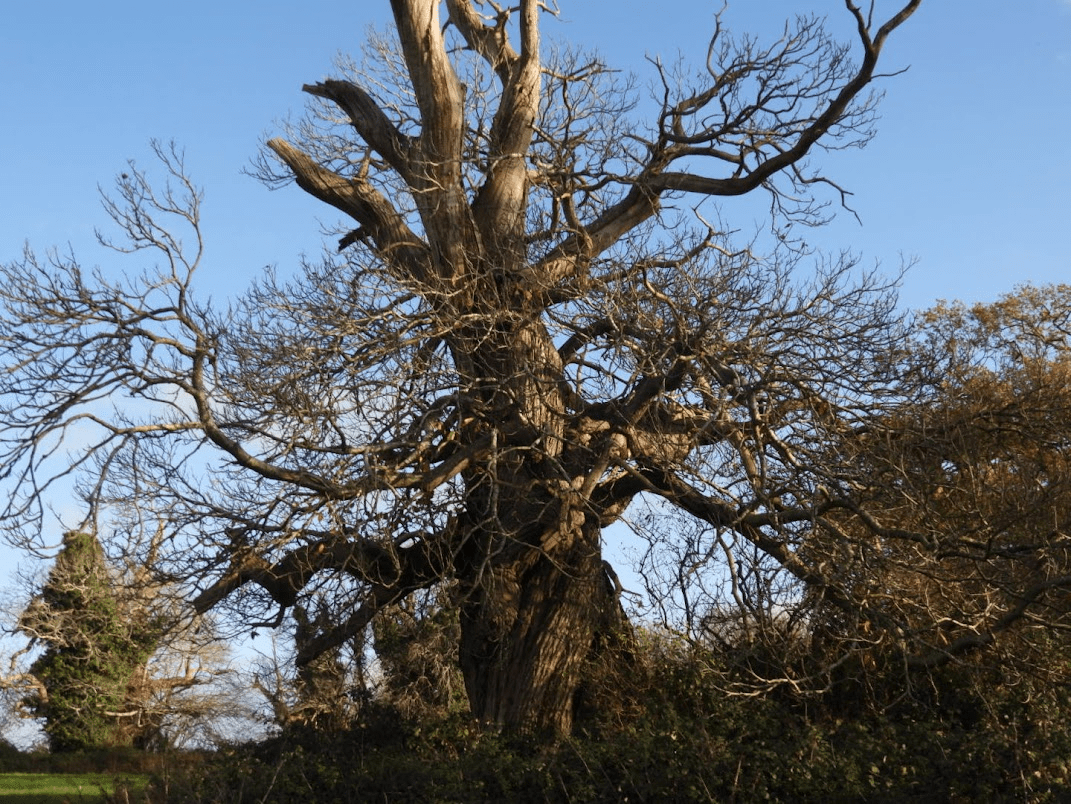

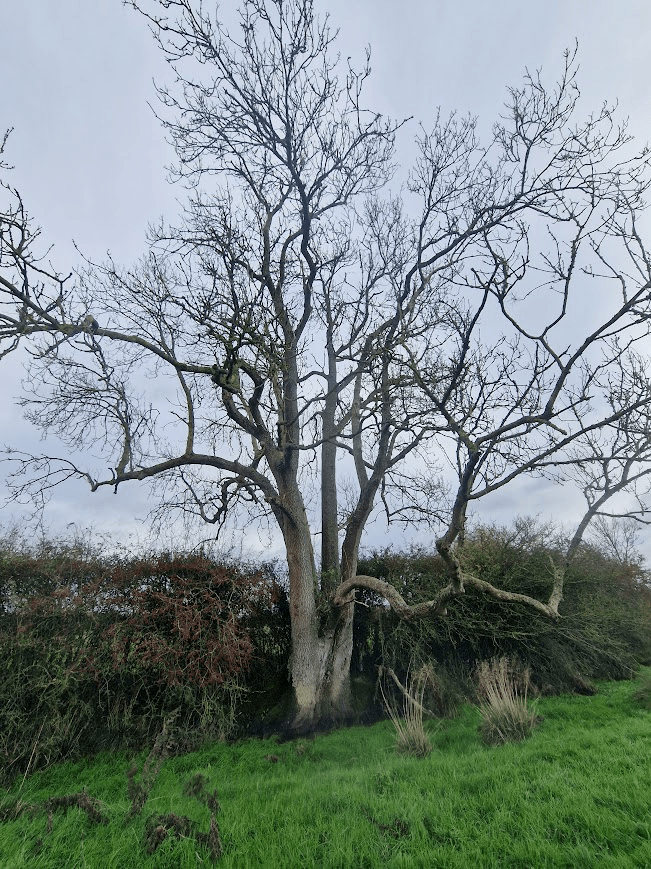

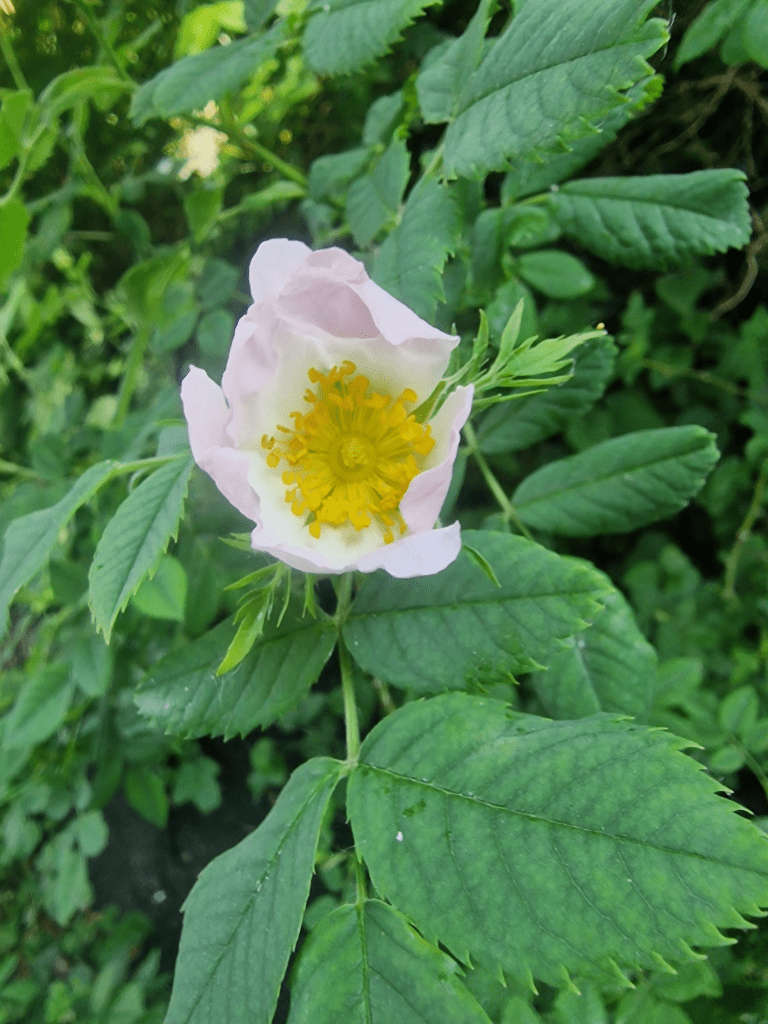

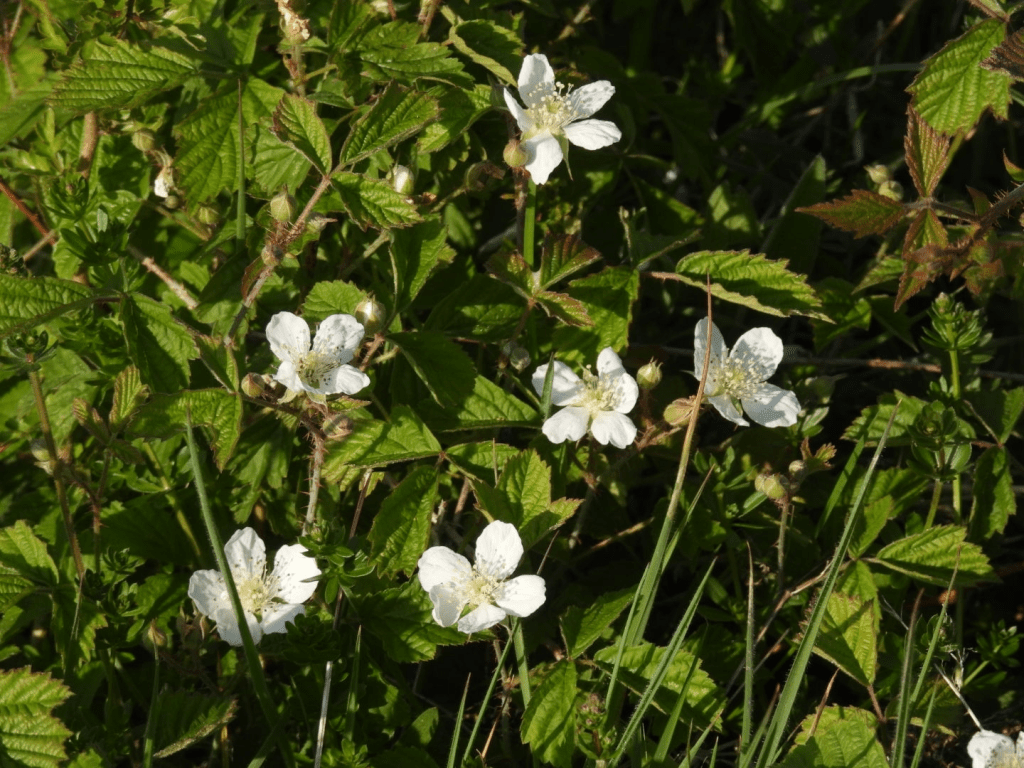

Hawthorn

Pedunculate Oak in front of two Sweet Chestnuts

Ancient Sweet Chestnuts

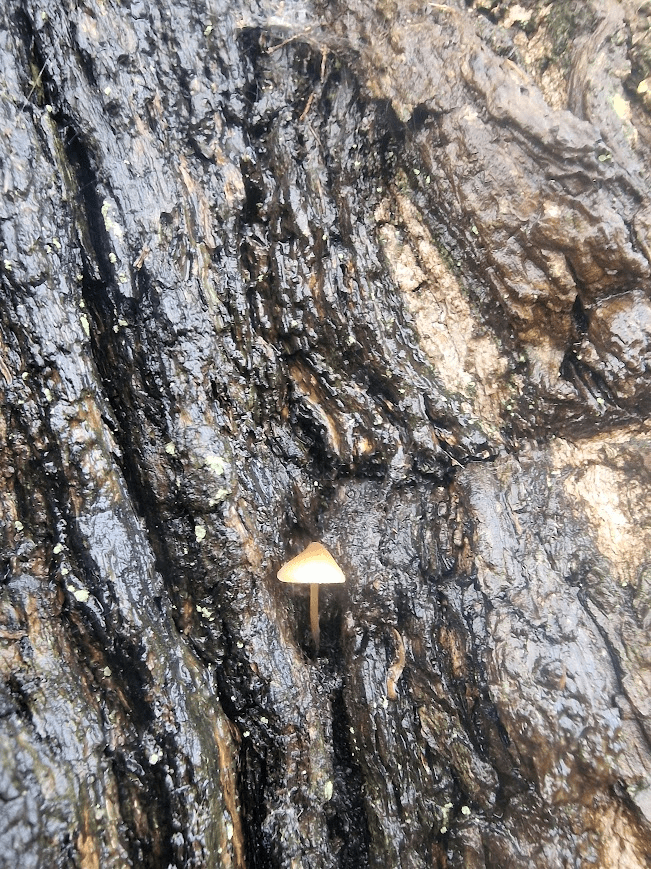

A Mycena sp. mushroom on the bark of one og these chestnuts

Ancient Sweet Chestnut

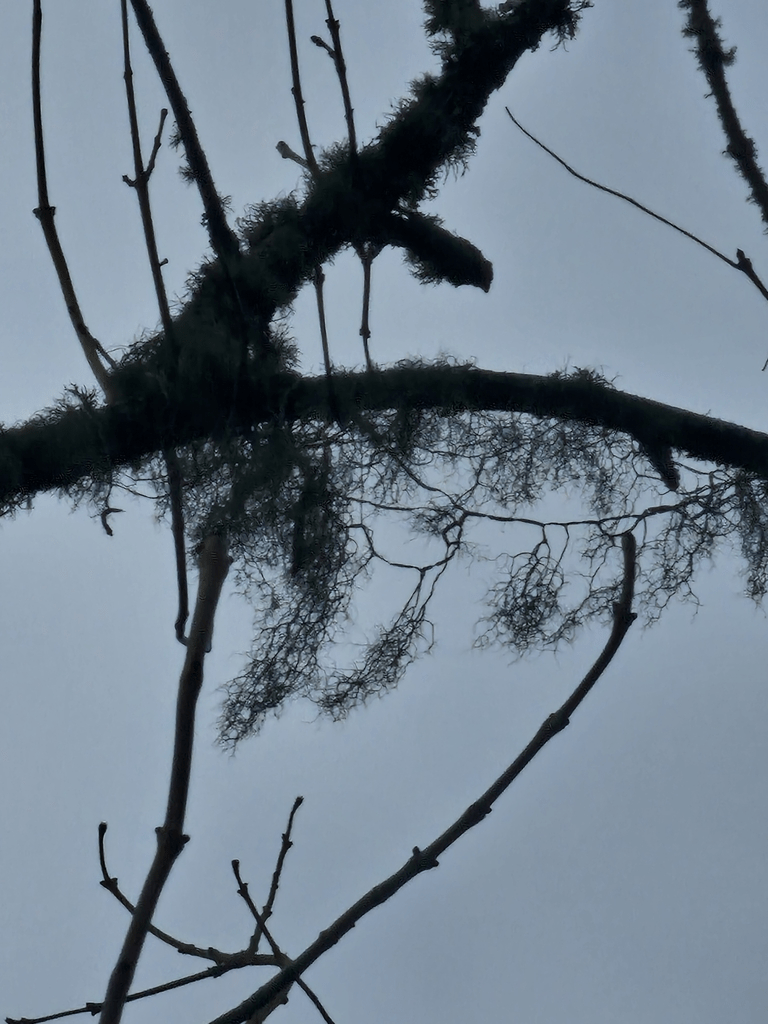

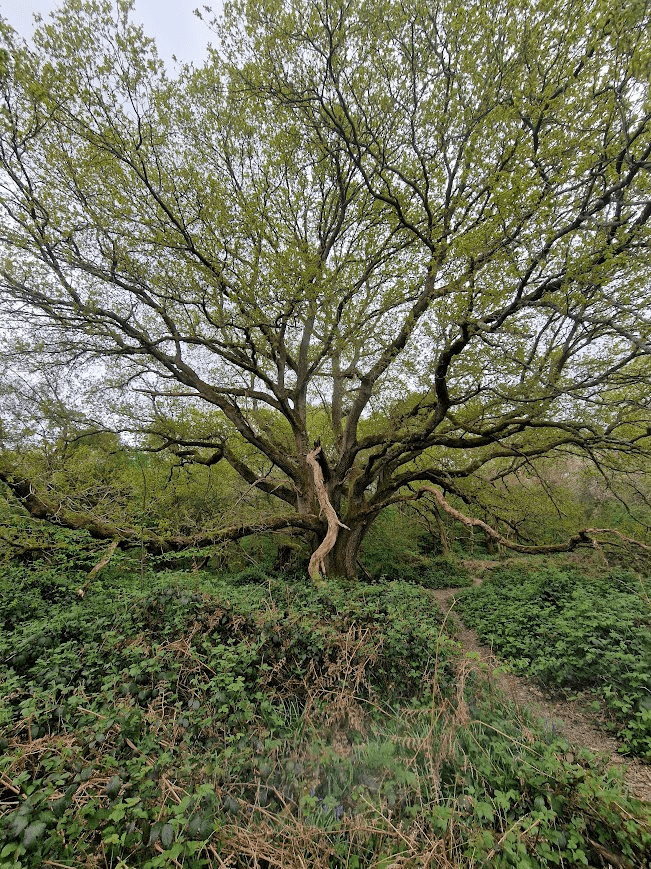

Ancient Yew

Hard to identify this as an ancient Yew, Taxus baccata, at first. It’s shape is nothing like the Yews of its native strongholds: chalk scarp-face woodland. It’s a pasture woodland Yew, sculpted by nibbling deer. Deer can tolerate Yew.

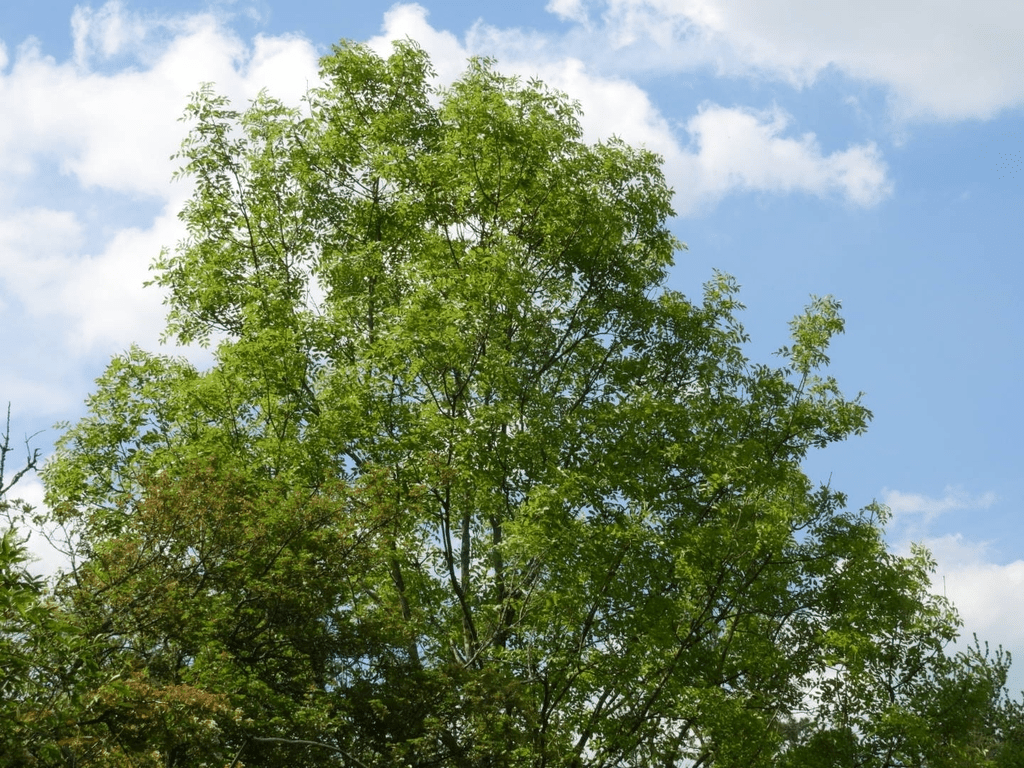

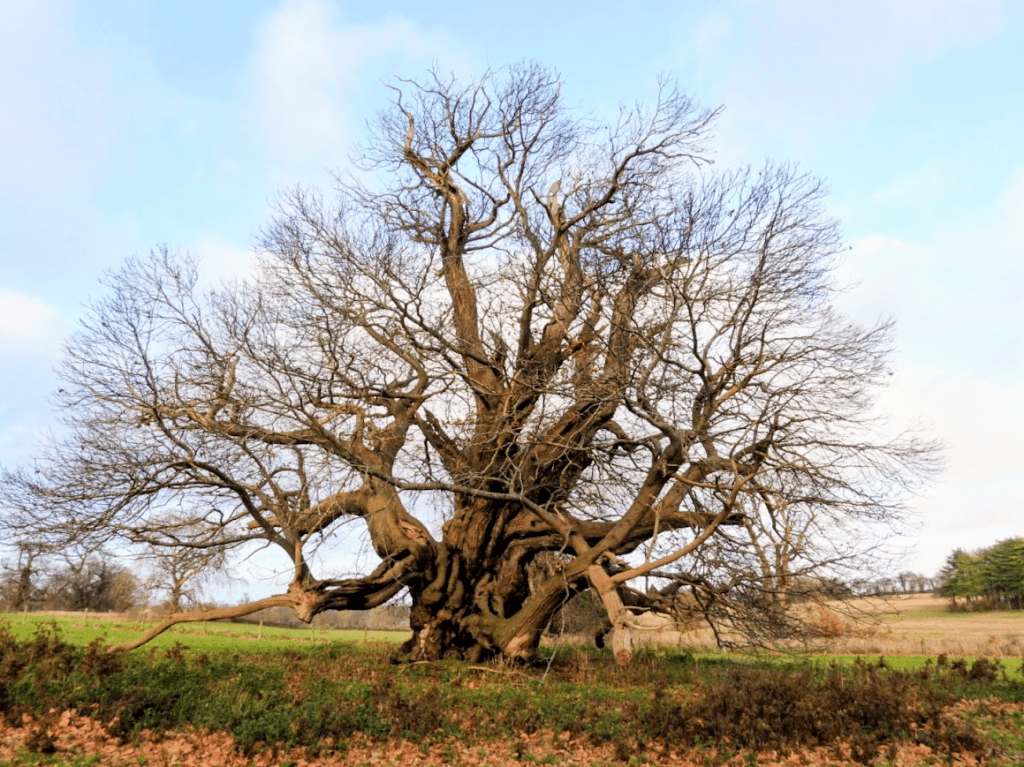

Pedunculate Oak

Lodge to Fredville Park

Historic England listing: Lodge to Fredville Park 11.10.63 II Gate lodge. Early C19. Painted brick with thatched roof. One storey and garret on plinth with dogtooth cornice to half-hipped roof with pierced bargeboards. Central stack with double polygonal flues. Single storey gabled porch with elliptical openings on all 3 sides, that to front with label hood. Arched 2 light wooden casements with label hoods either side of porch, with central four centred arched door with Gothick tracery. Canted bay with Gothick windows on left return front

A postscript

Right next to Fredville Park is the remains of the closed Snowdown Colliery.

The miners were on strike in 1984-85 and I remember well Brighton Trades unions collected food outside supermarkets to send to them. The strikers knew, as did we, that they were fighting the ruling class under Thatcher who wanted to close the pit. Forty years later, in 2025, a merchant banker has persuaded many working people in Kent that their enemy is migrants; but its the Tory ruling class that has impoverished them. The decline in class awareness and the ability of the ruling class to spin false narratives that are believed I find very sassy. Wake up people.