These organisms were found on a British Bryological Society South East Group (Sussex Bryophytes) field meeting. I would really recommend attending these meetings; they are very friendly and very accommodating of beginner bryologists (like me!). With us yesterday was pan-species listing guru Graeme Lyons. The bryologists Ben Bennat, Sue Rubinstein and Brad Scott made all the bryophyte identifications. My specific interests in natural history are birds and lichens; but I am trying to take a pan-species listing approach. No one can be an expert in everything so taking a pan-species listing approach is also an opportunity for social natural history; learning from others who know much more about specific areas of biology than you. My interest in pan-species listing is not the opportunity it provides for listing large numbers of species, but the opportunity it provides to learn more about your own patch and thus travel less, and thus minimise your carbon omissions. Local pan-species listing in your own patch means there will always be more things to find without having travel miles.

Lichens of southerly downland churches: Sullington St Mary’s Church

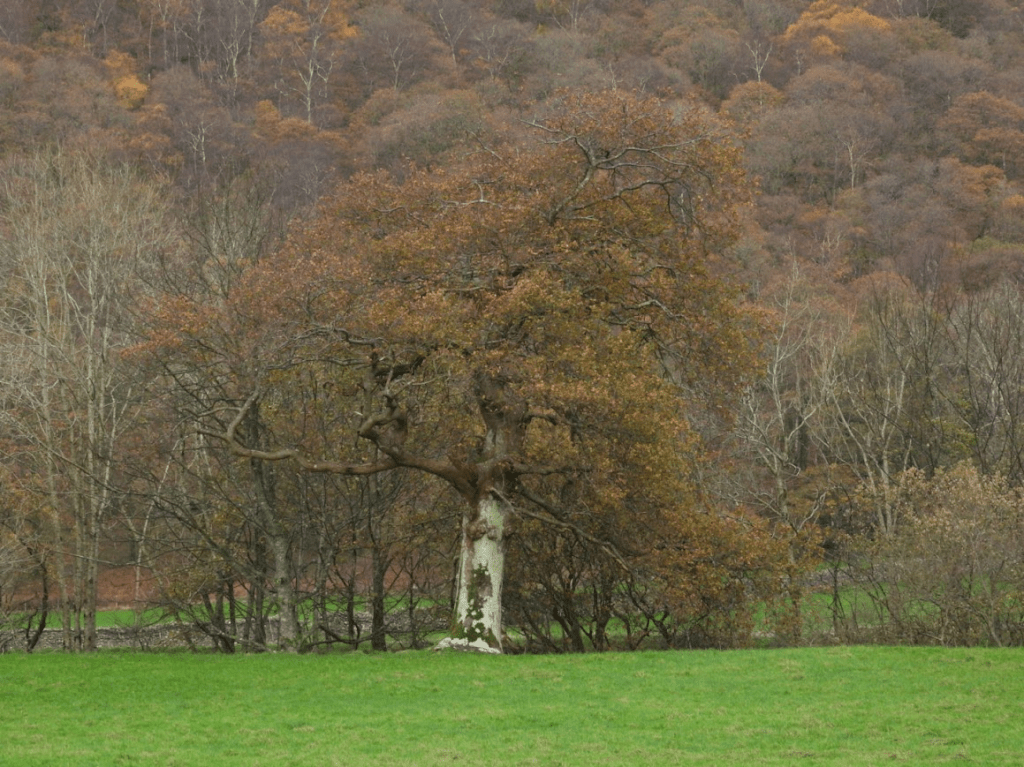

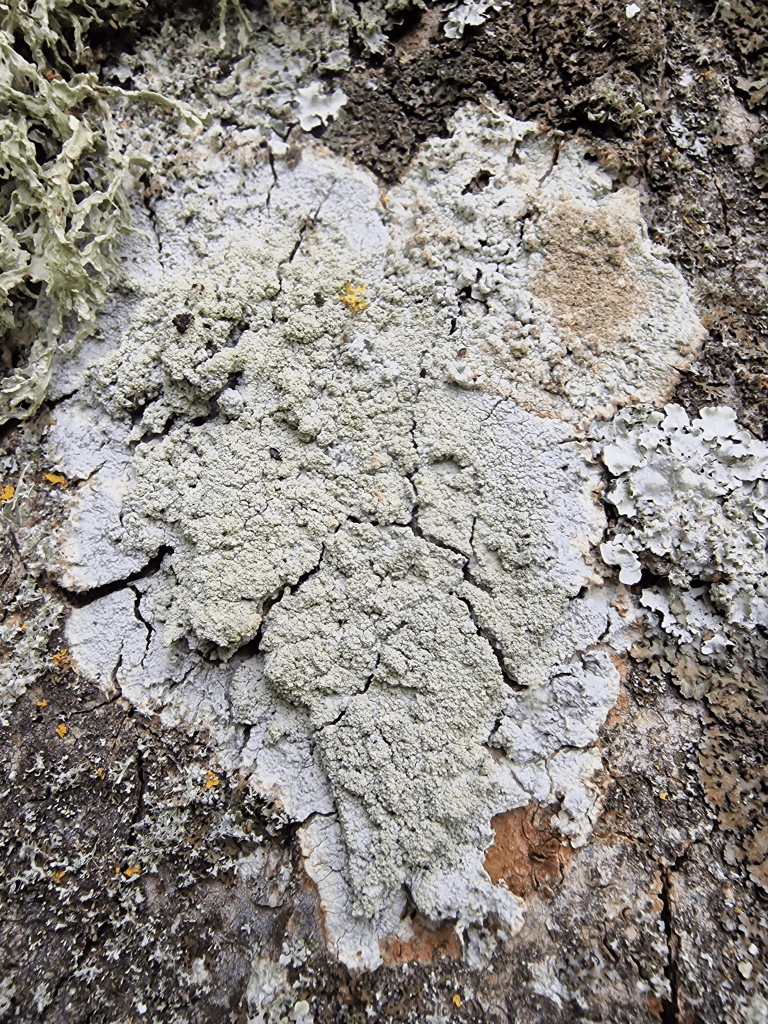

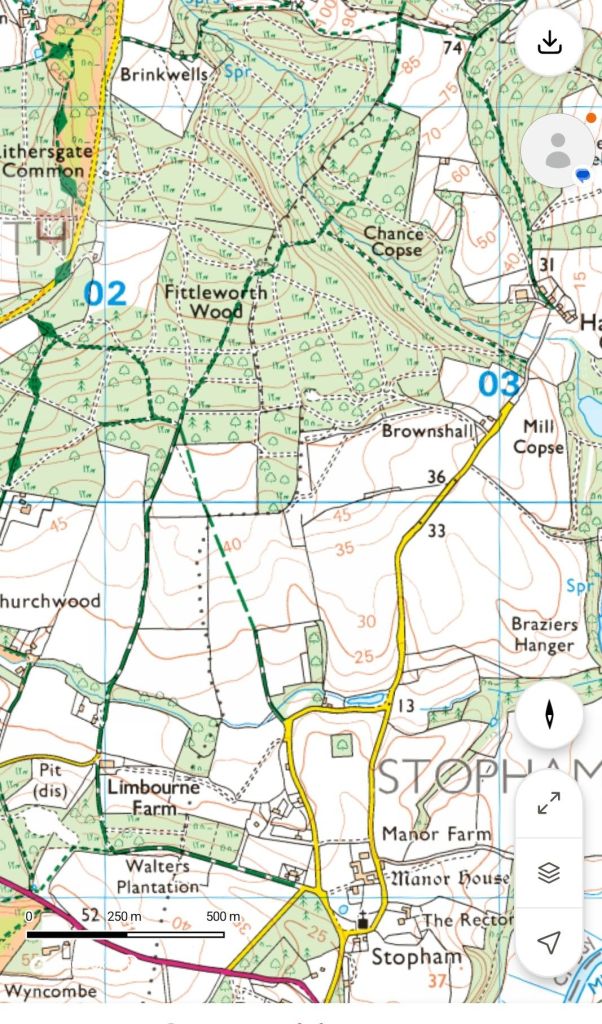

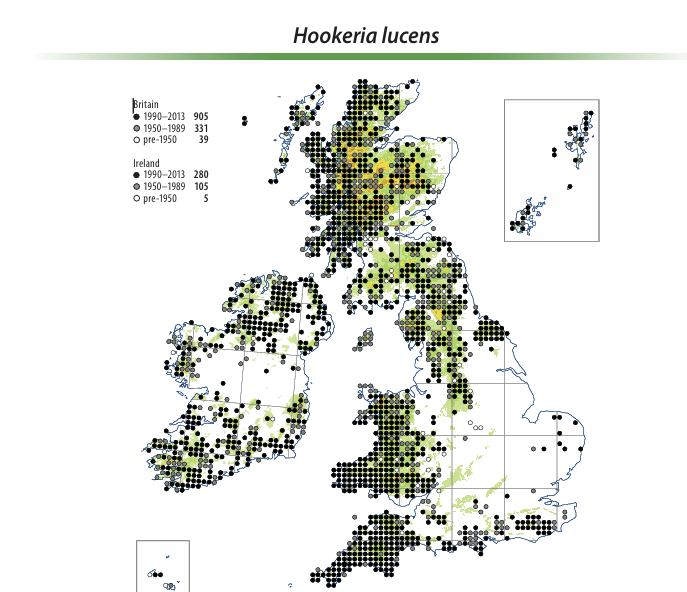

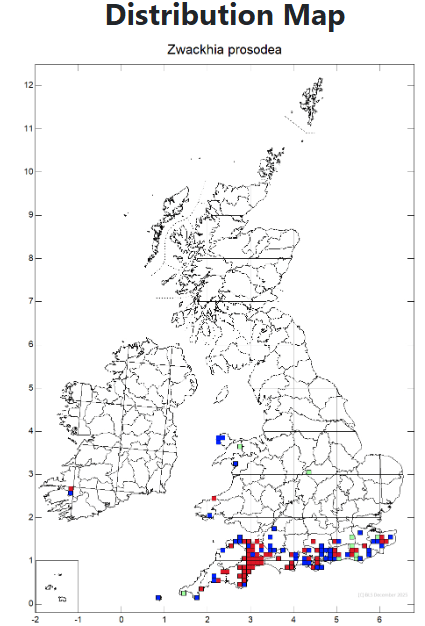

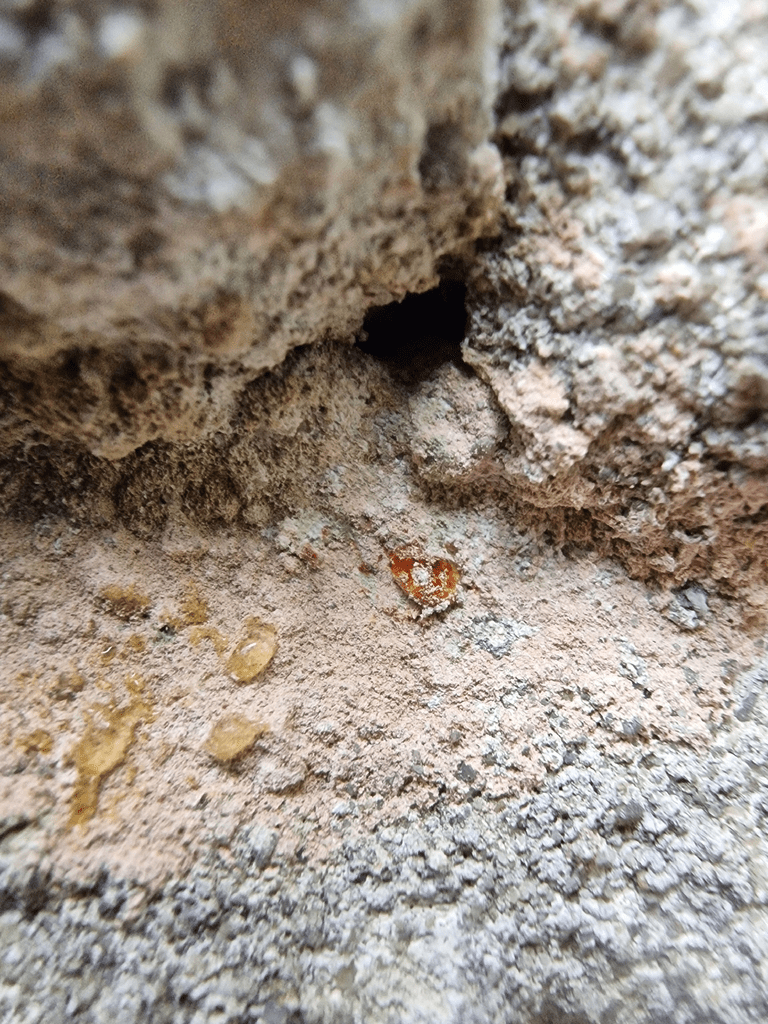

Zwachhia prosodea on ancient yew. A Near Threatened (Red List) Nationally Scarce lichen. This is not a species specifically of chalk but it is very much a species of the south. It grows on ancient trees – mostly Pedunculate Oak and Yew; but I have only seen in on Yew, all in church yards – East Chiltington, Coldwalhtam and Sullington. It is a Graphidaceae family lichen. Typically this family of lichens can only be identified by spore microscopy; but Z. prosodea has such distinct lirellate apothecia (writing-like fruiting bodies) it can be identified morphologically.

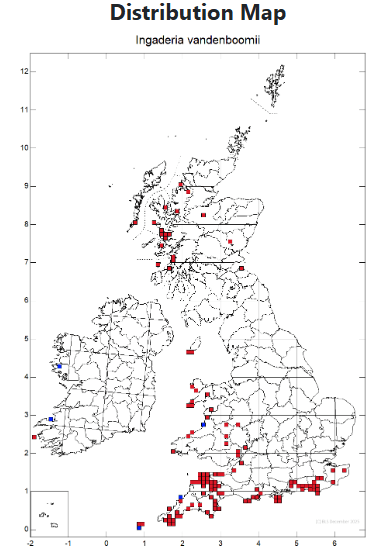

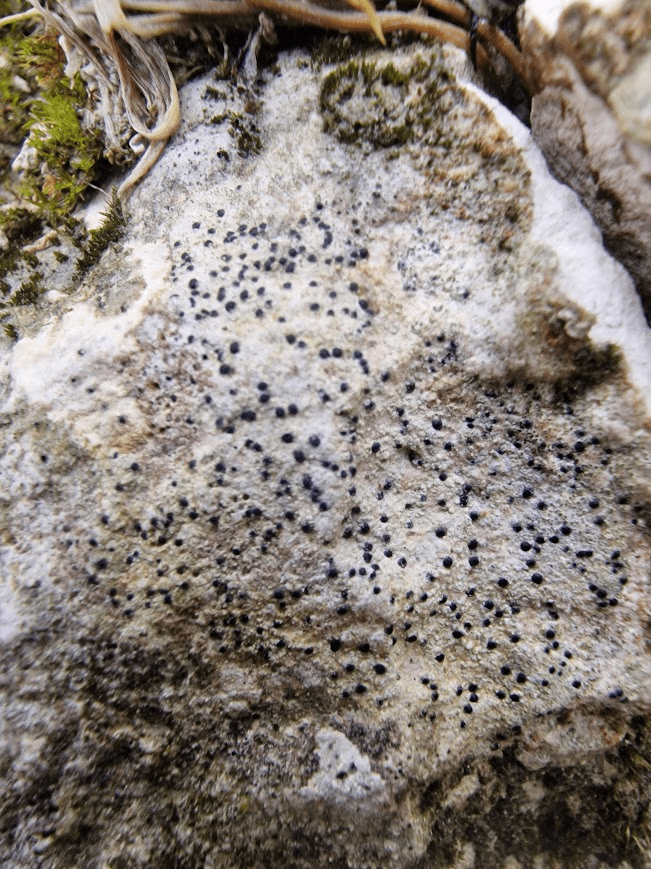

Ingaderia vandenboomii on north wall of church. Again not a species of chalk but a species of the far south. A Nationally Scare lichen but I find it quite often on the north walls of Sussex flint and mortar churches near the coast; I have seen it on the north walls of St Peter’s, Southease; St Thomas à Becket’s, Pagham; St Nicholas Church, Bramber; and St Mary the Virgin, Stopham. Identification of this lichen is by spot reagent chemical tests. It doesn’t react to potassium hydroxide (left drops on photo); but turns red immediately to sodium hypochlorite (centre drop on photo)

Lichens of Chalk Downland

Cladonia furcata. Not a species specifically of chalk, but one of the few Cladonia species found on chalk grassland.

Enchylium tenax Distributed throughout the British and Ireland but more common in the south. Not a lichen specific to chalk; but one of the few jelly lichens that grow on chalk

Verrucaria muralis Very widely distributed. Not a lichen specific to chalk; but one of the few lichens that grow on chalk pebbles, and is abundant on chalk pebbles. Oliver L. Gilbert (1993). The Lichens Of Chalk Grassland Lichenologist 25(4): 379-414 is one of the very few articles on lichens of chalk. This is a provisional identification as spore microscopy is required to confirm the identification; but its morphology and its abundance on chalk pebbles according to Gilbert make it highly likely that this is V. muralis

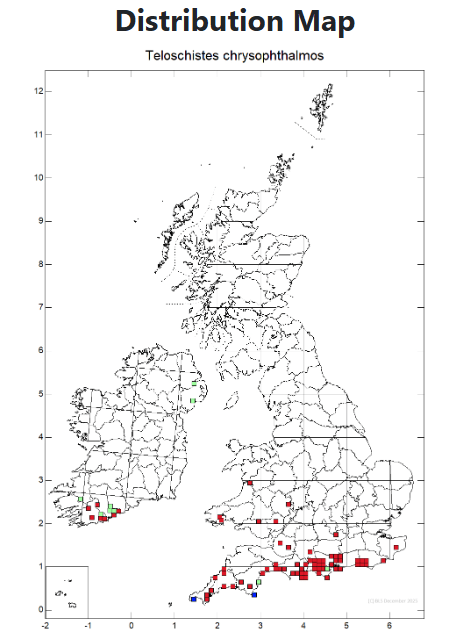

Teloschistes chrysophthalmus Golden-eye Lichen on Hawthorn. I see Golden-Eye frequently on Hawthorns of the South Downs, particularly on the downs north of Brighton and Lewes

Confined mostly to Chalk Downland Hawthorns in the south. See my blog post of two years ago 12 Golden-Eye Lichens on one Hawthorn. The resurgence of the once-thought-extinct Teloschistes chrysophthalmus on the South Downs. 06.04.24 This is from my blog: Sim Elliott: Nature in Sussex: nature journeys made by public transport 2020-2024. Whilst I do not publish new posts to this blog the blog posts are still available; to act as a compendium of nature sites that can be visited in Sussex by public transport

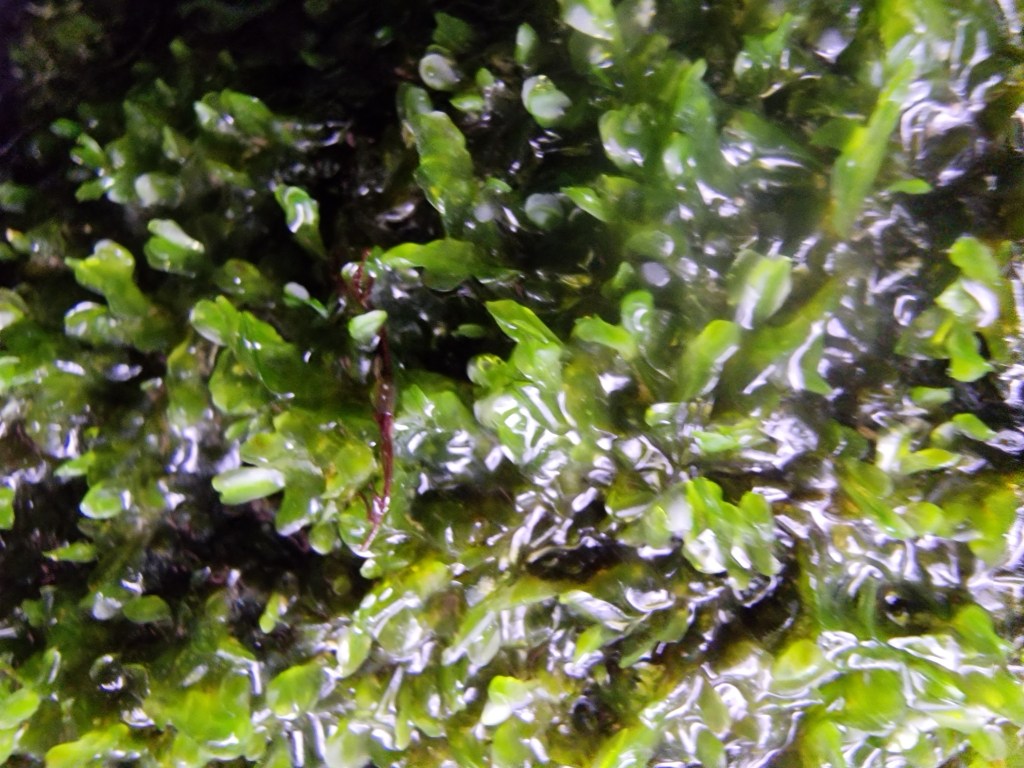

Chalkland bryophytes

None of these identifications were made by me; they were all made by Ben Bennat, Sue Rubinstein and/ Brad Scott

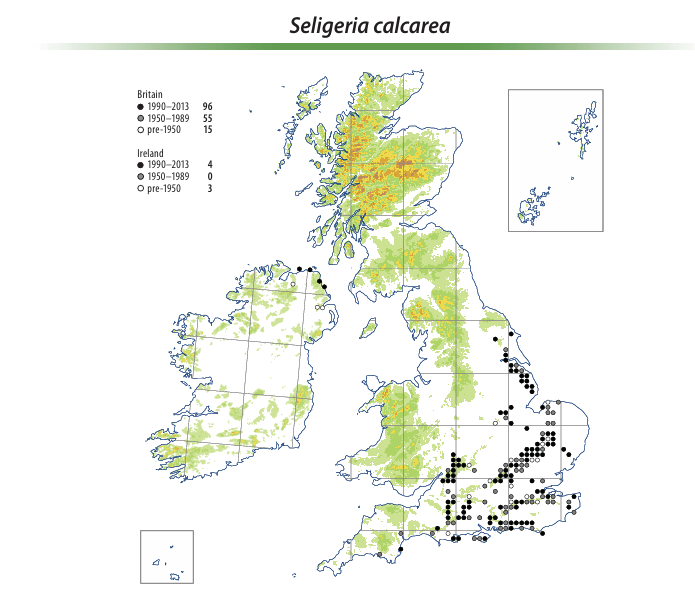

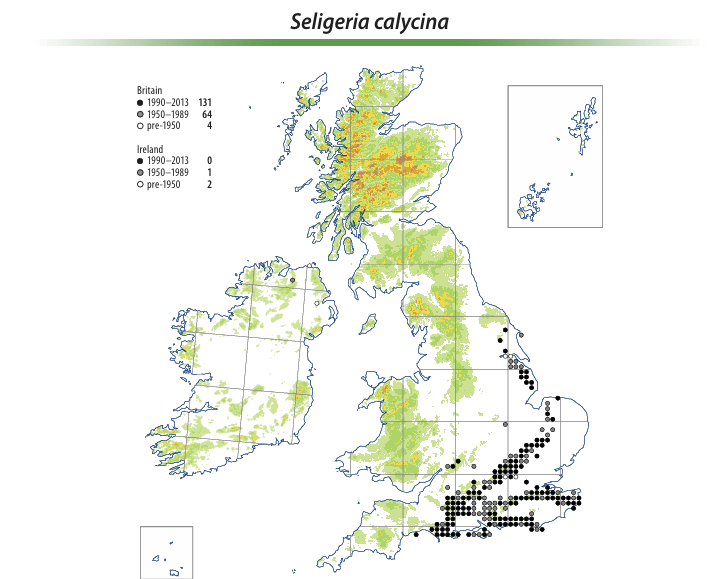

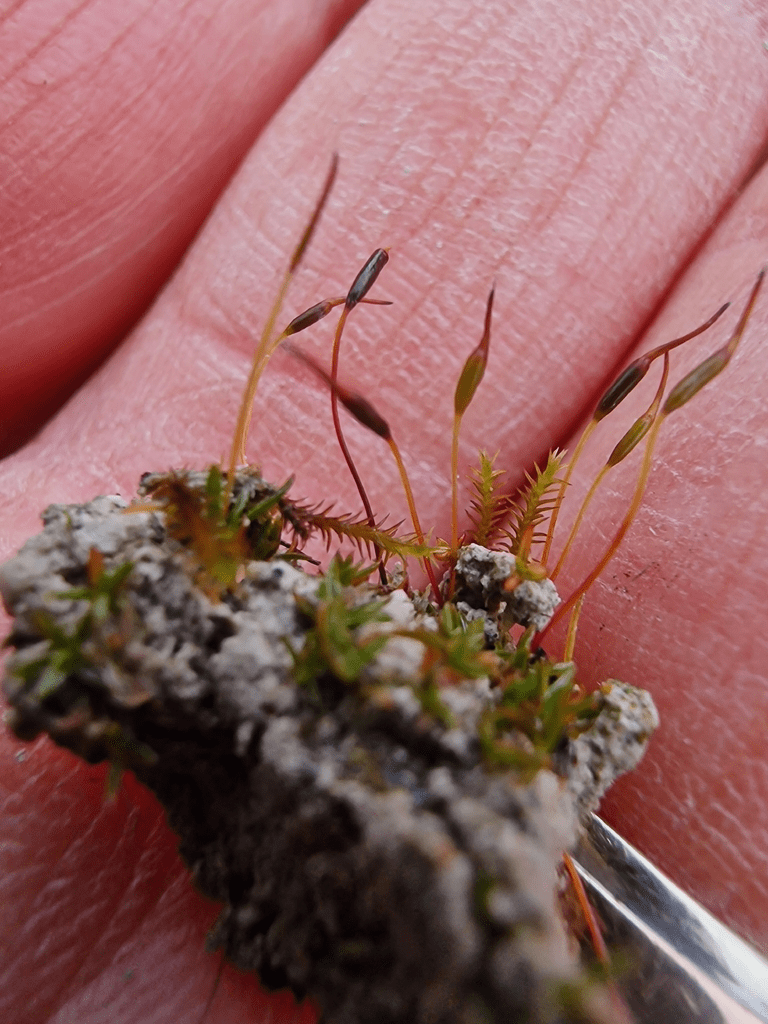

Seligeria calcarea Chalk Rock-Bristle or S. calycina English Rock-bristle – to be confirmed. on a shaded chalk bank in a holloway bostal

A Seligeria on chalk fragments in a sheltered place, such as a north-facing holloway bank or a woodland floor, is almost certainly going to be either this species or S. calycina. Because the plants are so small, this species pair is not always easy to separate in the field, unless dehisced capsules are present (usually March to April). Then you will easily see that the capsule of S. calcarea is widest at the mouth. Capsules of S. calycina characteristically narrow a little at the mouth when mature. Beware though – like many mosses, capsule shape does not develop fully until the spores are ripe. British Bryological Society Seligeria calcarea

Aloina aloides Common Aloe-Moss

Not solely chalk but A species of bare but not regularly disturbed ground and

soil in a variety of situations, usually base-rich, but occasionally on ground that appears to be circumneutral. The most characteristic habitat is in old pits and quarries on chalk and limestone, growing on the floor or on earthy rock ledges, but it is also frequent in some districts on old or weathered mortar on walls and ruined buildings. .. It is occasionally found on bare patches in calcareous grassland and on soil on natural rock outcrops; other habitats include chalky and earthy banks by lanes, coastal slopes and cliffs, clay in brick pits, calcareous dune sand and gravel, and path edges and earthy rubble (here often only as a temporary colonist). British Bryological Society Aloina aloides

Pleurochaete squarrosa Side-fruited Crisp-moss

Grows loosely tufted or scattered and mixed with other plants on sandy or calcareous ground. Usually found in unshaded habitats in sand dunes, maritime grassland on cliffs, chalk and limestone grassland, and in chalk and limestone quarries. British Bryology Society Pleurochaete squarrosa

Orthotrichum anomalum Anomalous Bristle-Moss

OK! Not a chalk moss; but what a beauty; on a tomb stone in Sullington churchyard. more or less ubiquitous on concrete, gravestones, wall tops and other man made structures except in the most polluted parts of Britain. Also common on exposed limestone, but absent from chalk. British Bryology Society Orthotrichum anomalum

Invertebrates

All identified by Graeme Lyons

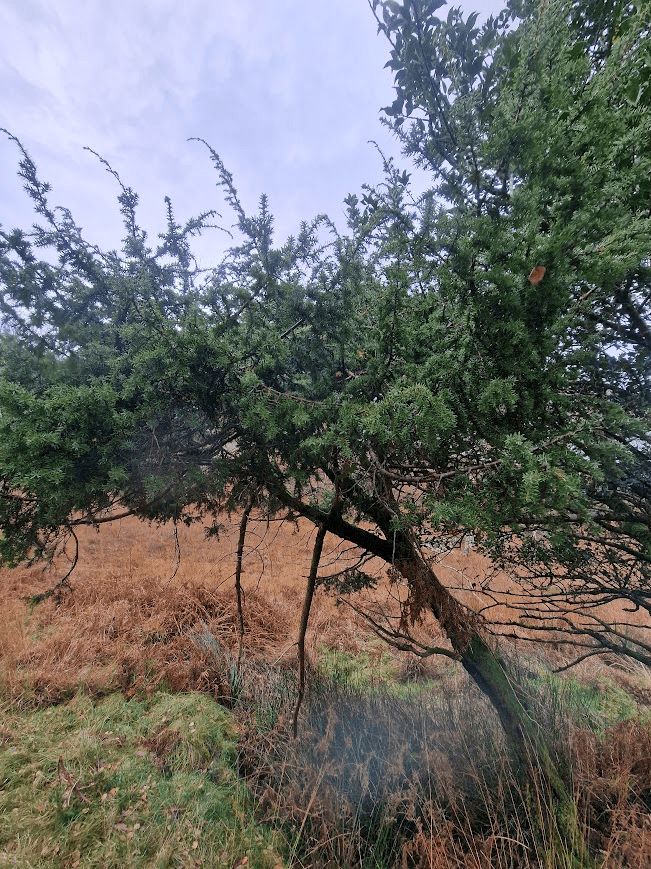

Cyphostethus tristriatus Junipers Shield Bug.

Formerly a southern shieldbug but has had a significant range extension of late. Formerly restricted to Juniper woods in southern England, the Juniper Shieldbug (Cyphostethus tristriatus) is now common across southern and central England, having colonised planted Junipers and Cypresses in gardens. It has also been recorded on native Juniper in northern England and Scotland. North West Invertebrates, Juniper Shieldbug

Distribution map from National Biodiversity Network Atlas

Corizus hyoscyami Cinnamon Bug

Although historically confined to the coasts of southern Britain, this species is now found inland throughout England and Wales as far north as Yorkshire. It is associated with a range of plants, and overwinters as an adult, the new generation appearing in August-September. Nymphs are yellow/red-brown in colour and also rather hairy. British Bugs Corizus hyoscyami

and Graeme made this extraordinary find

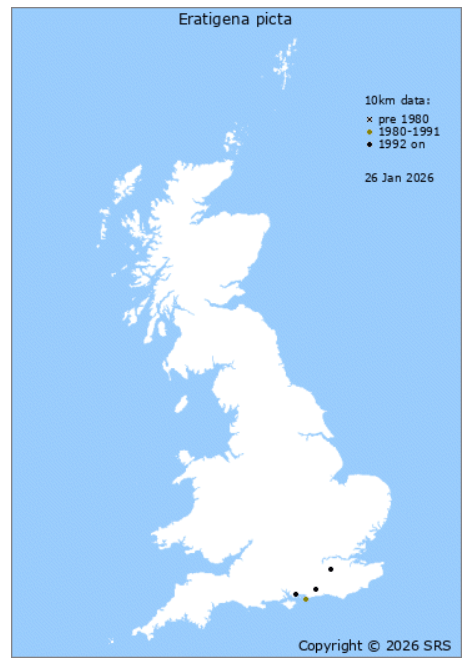

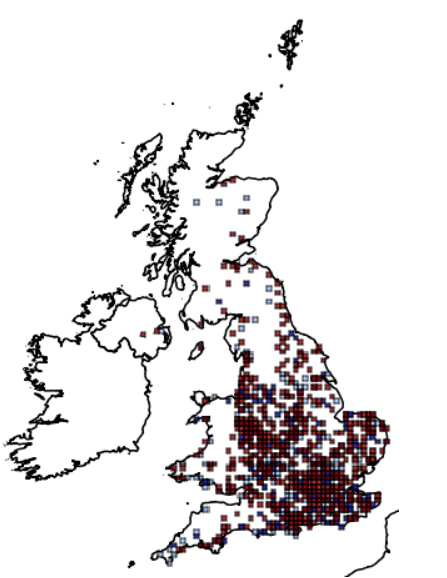

Eratigena picta

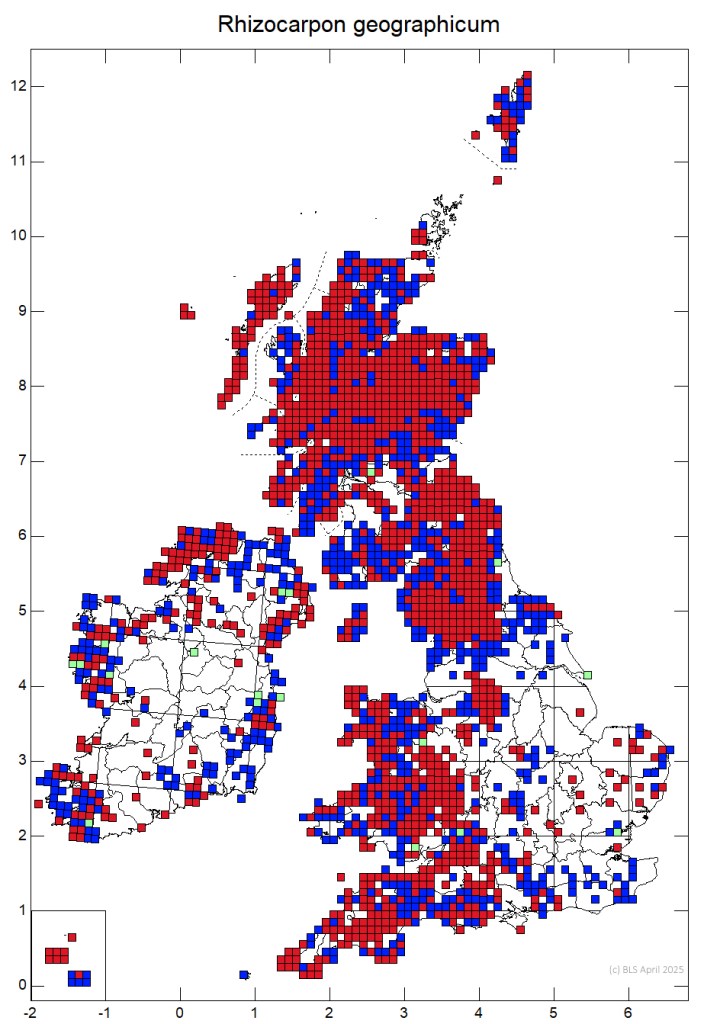

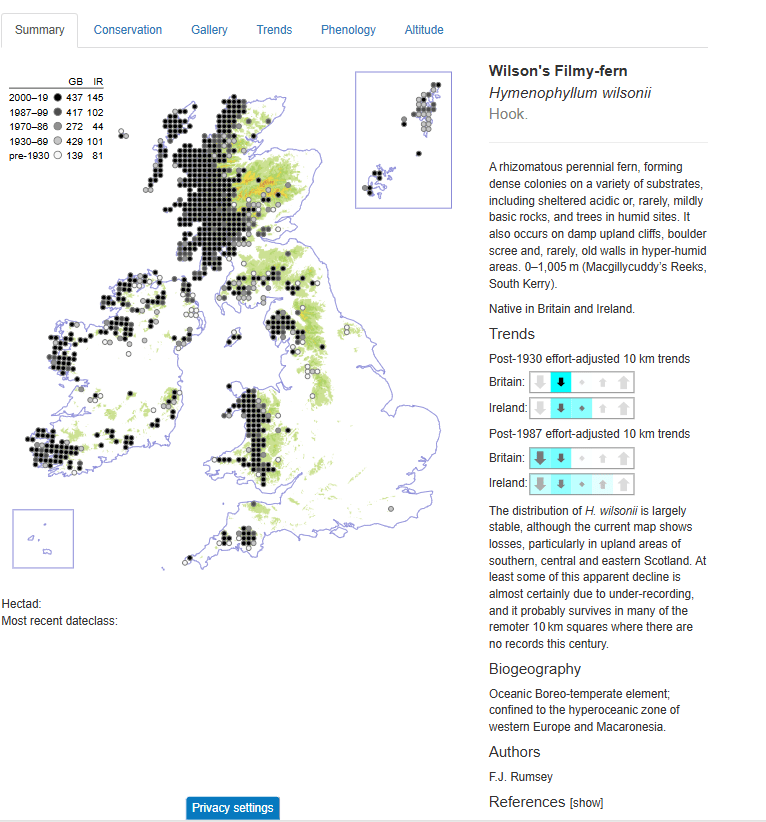

Distribution map from Spider and Harvestman Recording Scheme website

IUCN Red List status Vulnerable (VU)