The church of Mary de Haura [de havre; of the harbour] was built built between ca. 1125 to ca. 1219, with funds from the 2nd Baron of Bramber, when he returned from the First Crusade Sussex: West, Pevsner Architectural Guides, The Building of England revised (2019) by Williamson, Hudson, Musson & Nairns. The de Broase were the Barons of Briouze in Normany, made Barons of the Norman Rape of Bramber by William the Conqueror. The port fees from Shoreham harbour, built by the First Baron of Bramber also funded the long building of St Mary de Haura

The exterior of the church:

The port was of great importance to the new Norman rulers as Shoreham was one of the main ports for Normandy. As a consequence, the Adur valley is aid to have been one of the three most densely populated parts of England (G Standing p93). …, the river silted up and a new port was built on the coast, protected by the de Braoses of Bramber. Its church … was granted to Saumur in 1096 (VCH 6(1) p168) to which the de Braoses had links through their foundation of Sele priory at Upper Beeding.

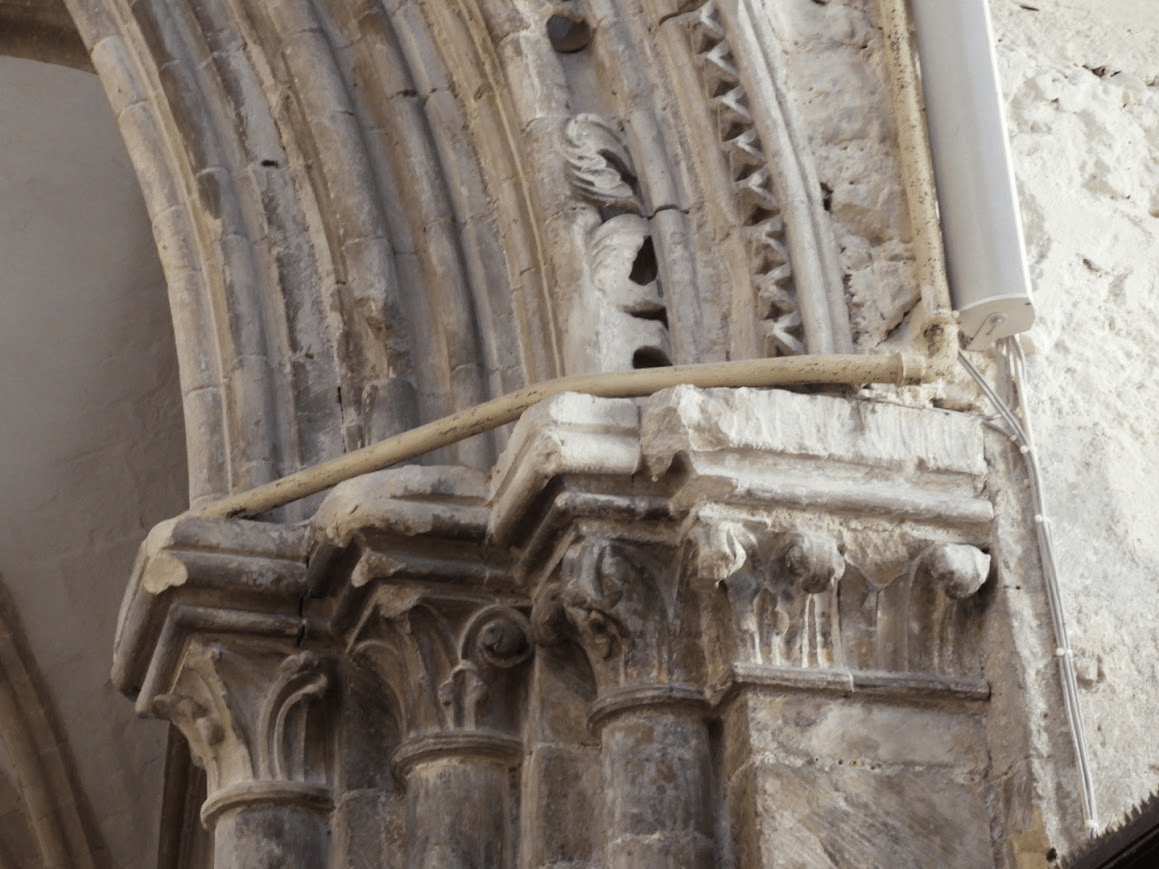

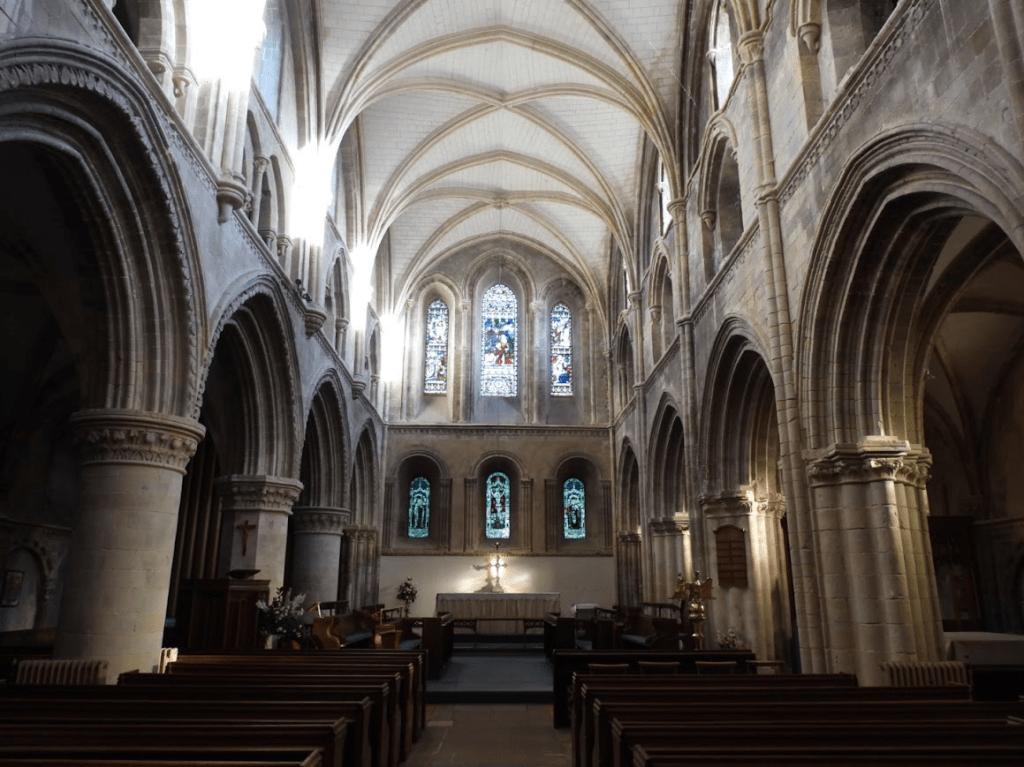

The transepts, crossing and lower tower were built between about 1125 and 1140, followed by a mid-C12 nave of which less than a bay remains [most of the nave was demolished]. The upper tower followed shortly after and the choir was rebuilt, probably between 1180 and 1210. Despite many puzzles, it contains some of the finest work of the period in England. Shoreham Sussex Parish Churches Mary de Haura, New Shoreham, retrieved 02.12.26.

The sculptured foliage which this post focusses on, are mainly in the choir. When I revisited St Mary de Haura in December 2025 (I have visited the church many times) what really struck me, was the sheer abundance of carved foliage in the choir.

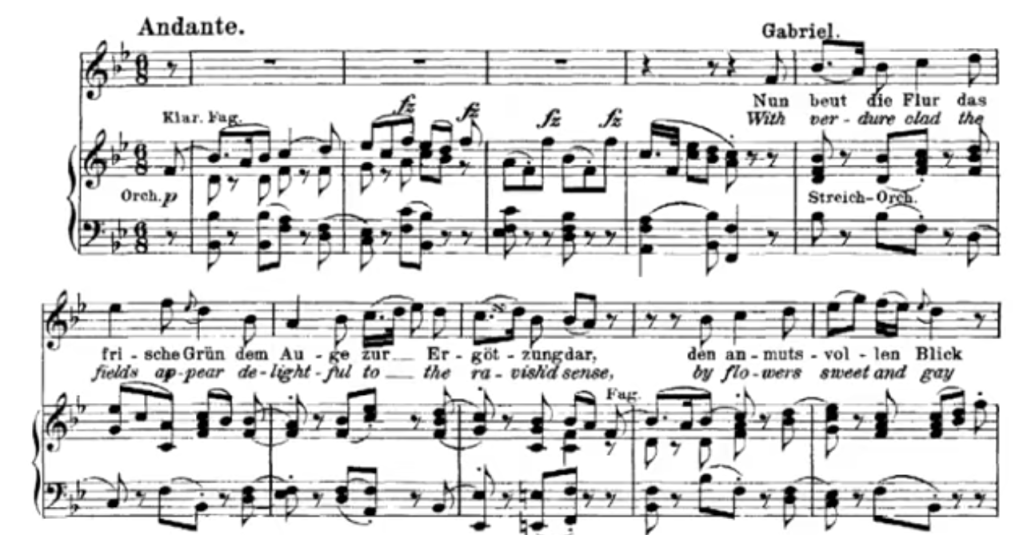

The lyric with verdure clad from Haydn’s oratorio The Creation, popped into my head. The availability of that lyric to my memory was probably because discussion of the origins of the lyrics of The Creation formed a large part of my A level music lessons (1978-80) at Brighton and Hove VIth Form College as The Creation was one of the set compositions for the examination. The Creation was written between 1796 and 1798 and celebrates the creation of the world. The original English libretto by Johann Peter Salomon was given to Haydn in 1795. It is derived from the Book of Genesis (King James Version) and Milton’s Paradise Lost. The original English libretto was translated into German by Baron Gottfried van Swieten for Haydn. But the common English version sung today is a re-translation from that German translation, which leads to some clunky language e.g. with verdure clad the fields appear and straight opening her fertile womb, the earth obeys the word, and teems with creatures numberless, in perfect forms and fully grown. Cheerfully roaring, stands the tawny lion. With sudden leaps the flexible tiger appears.

The aria With verdure clad the fields appear is sung by the archangel Gabriel (typically by a woman a soprano soloist). It describes the creation of plant life on the third day, celebrating the beauty and abundance of nature, including fragrant herbs, healing plants, and fruit-laden boughs

With verdure clad the fields appear

delightful to the ravish’d sense;

by flowers sweet and gay

enhanced is the charming sight.

Here vent their fumes the fragrant herbs;

here shoots the healing plant.

By load of fruits th’expanded boughs are press’d;

To shady vaults are bent the tufty groves;

The mountain’s brow is crown’d with closed wood. Retrieved from The Choral Art Alliance of Missouri. Haydn’s Creation Lyrics 03.01.26. You can listen to Emma Kirby’s performance of the aria with The Academy of Ancient Music conducted by Christopher Hogwood at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IqKGFtTGUXY&t=16s

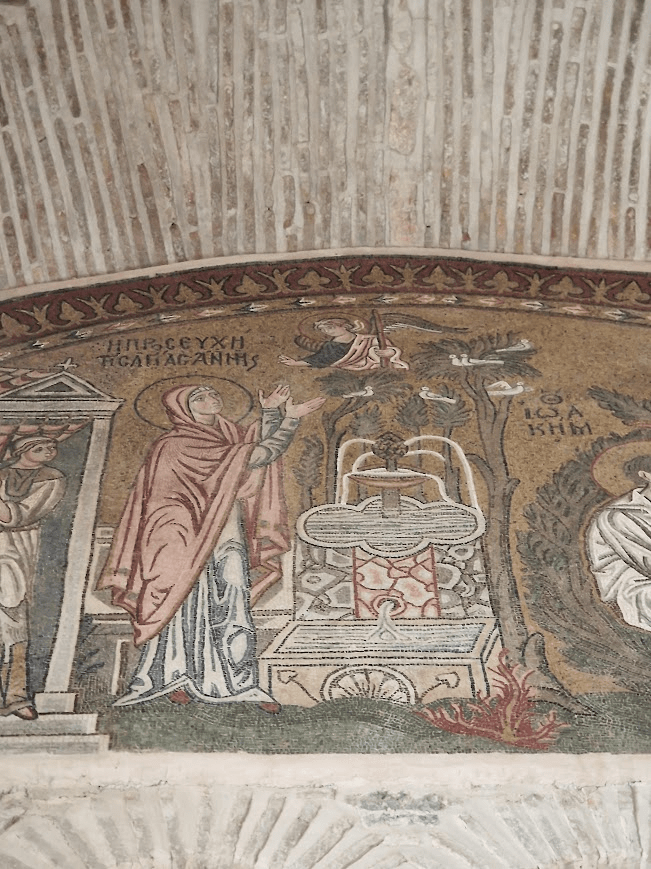

My interest in how landscape and botany are represented in medieval churches was engendered by taking a module on Byzantine art during studying for an MA in History of Art at the University of Sussex, 2003-2005. This module was not about landscape or botany; it was about the iconology of Byzantine art and production techniques, particularly mosaics, but because I was always always interested in landscape (I did A levels in Geology and Geography as well as Music, and spent a lot of time walking round the countryside of Sussex on A level field trips, and walking on the Downs at weekends with my Grandfather, an agricultural labourer on a farm in Rottingdean). I ploughed a lonely furrow researching the representation of gardens and wildernesses in the 1316-1321 mosaics of the Annunciations to St Anna and St Joachim in the narthex (entrance area) in the Church of the Chora Monastery, as when I took my MA, little research on landscape in Byzantine mosaics has been undertaken. The Chora Monastery is in Constantinople (now Istanbul). The Annunciation to St Anna and St Joachim is part of the cycle of representations of the life of the Theotokos (mother of god) and life of Christ that appears in all Byzantine (Greek Orthodox) churches. This scene is not typically depicted in western art, as its story derives from the apocryphal Protoevangelion of James, i.e. a text not accepted as canonical in western Christianity. In Byzantine iconology, Joachim is always presented in a wilderness (dessert) and Anna is shown in walled garden (a symbols of virginity in Medieval art).

The Church of the Chora Monastery is renowned … for its well-preserved mosaics and frescoes. It presents important and beautiful examples of East Roman painting [and mosaics] in its last period [the Palaiologoi dynasty, 1259 to 1453]. … The name “Kariye” (Turkish …: village) originated from an ancient Greek word “Chora“ (χώρα) [which] means “in the fields” or “in the countryside” because the old church and monastery remained outside the walls of Constantinople. [The] Theodosian walls [were] built in 408-450. [T]he fact that the word Chora is written along with the names of both of them on the mosaics depicting Jesus and Mary inside the church shows that it has a mystical meaning too. [The] Chora Church was originally built in the early 4th century as part of a monastery complex … during the reign of Emperor Iustinianos [Justinian] in the 5th century. Kariye Mosque retrieved 03.01.26.

The Annunciation of Mary’s Birth to Anne, The Greek inscription in the scene reads “Saint Anne is praying in the garden”

Photo from my visit to the Chora Monastery in Istanbul in 2014

I looked hard at how plants were represented in this mosaic version of the Annunciation, but I was unable to demonstrate any connection between plants in the Chora’s countryside location and the nature of the flora depicted; although The Protoevangelium of James sates that Anna went down to the garden to walk. And she saw a laurel, and sat under it, New Advent, retrieved 03.01.26. There also appears to be no connection between the carved foliage in St Mary de Haura and “real” flowers around Shoreham or anywhere. Flora in medieval religious art are not a representations of particular botanical species; flora, instead, symbolically represents core aspects of Christian belief; e.g. God’s creation, purity, resurrection, and eternal life. Some specific species did have set significations, e.g. Lilies of the Valley represented the Virgin and virginity. Although specific species were only rarely depicted in the medieval period; they become common in Western religious art in the Early Modern period of the Renaissance e.g. by Van Eyck, see Paul Van den Bremt (2011) translated by Lindsay Edwards A Garden Full of Symbols. Flora in the Paintings of Van Eyck retrieved 03.22.26

I am an atheist and do not believe in a creation of nature by god nor do I believe that plants have any religious meaning. However, I am very interested in how people construe nature in art. Symbolic religious interpretations of nature are part of the history of ideas in the religious art of both Western and Eastern Christianity. Christian symbolic motifs are very important to understanding the decoration of Medieval churches, in the eyes of those who designed and built them and worshiped in them.

Before Christmas, I went holiday to Athens with my husband; our first holiday abroad for 11 years. We went to the Monastery of Daphni, whose mosaics were created ca. 1100 during the Byzantine Komnenoi dynasty

Again the plants in this mosaic are not identifiable as specific botanical species. The trees look a bit like Allepo Pines, Pinus halepensis, common in Athens suburb, more than Laurel, as mentioned Protoevangelion of James. The birds, Sparrows, are named as Sparrows in Protoevangelion: And gazing towards the heaven, she saw a sparrow’s nest in the laurel New Advent, retrieved 03.01.26. They do indeed look like sparrows; but it is impossible to determine whether they are House Sparrows, Passer domesticus or Tree Sparrows, Passer montanus; both common in Greece and the Levants; but when the Protoevangelion was written (mid-2nd century AD) a distinction between Domestic and Tree Sparrows may not have been known

Joachim’s wilderness bush:

could be Olive trees, Olea europaea, which are a ubiquitous feature of the landscape of the eastern Mediterranean

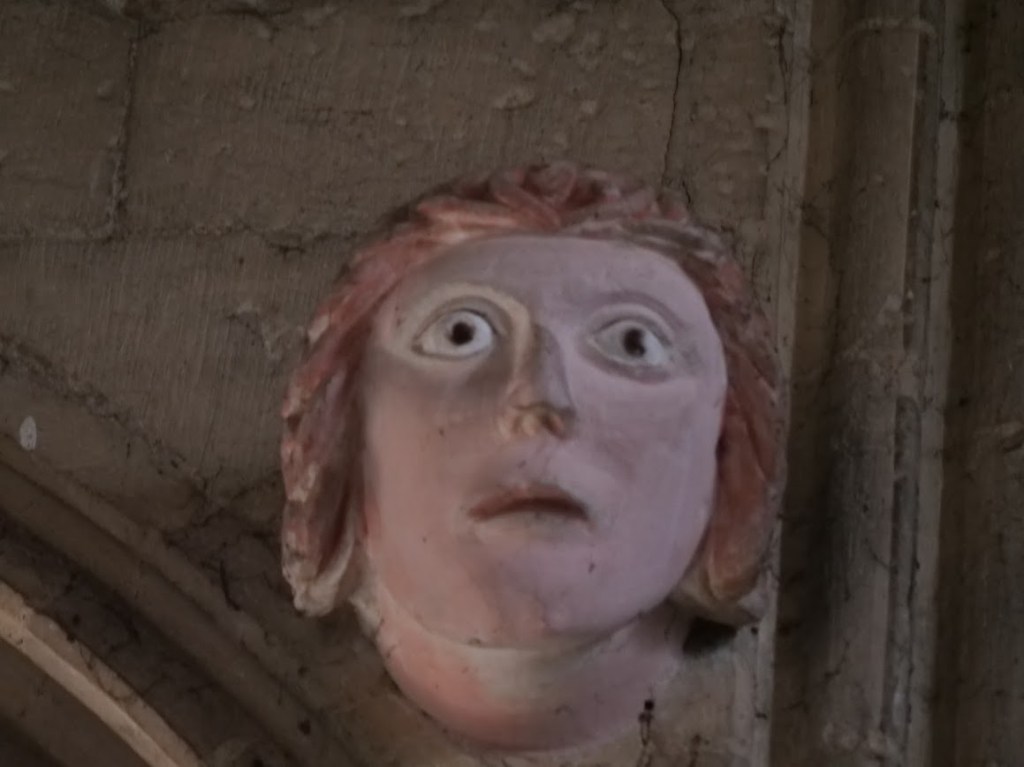

Sussex carved stone representations of foliage in C12 and early C13 Shoreham seem quite primitive compared with Byzantine mosaics of foliage in C12 Athens; but this is not an entirely fair judgement; mosaics partially look more sophisticated because they are made of brightly coloured glass and carved stone is grey; but it is only grey now because its original painting has been lost. In C12 and C13 churches, sculptures would have been painted in bright colours, see Tysoe Heritage Research Group. The recently repainted corbel heads in Boxgrove Priory Church, West Sussex nr. Chichester, give an impression of how colourful Sussex churches may have looked in Norman, Plantagenet and Tudor times, before Henry VIII’s reformation

However, to some degree Byzantine C12 mosaic foliage is more sophisticated than English sculpted foliage; as Byzantine mosaics attempt to represent specific plants (and specific people) figuratively (even if what they represent is mythical rather than real); whereas Norman masons crafted mostly decorative generic foliage patterns in English C12 not representation of specific plants, although they did produce foliate heads (Green Men), which attempt to represented mythic figures. However, both the generic foliage of the west and specific plants in the east signify ,same theological concept: purity, resurrection, the beauty of “Gods creation”.

James Kellaway Colling asserted in 1874 that Early English Foliage [in churches] probably culminated about the middle of the thirteenth century, but many excellent examples are as early as the end of the 12th century. It was evidently progressively developed from the foliage of the Norman era. … By the Perpendicular period [C14-C16 the final period of English Gothic Architecture]greater scope was given to sculpture than foliage, especially in large works. Shields and heraldic emblems were commonly used, and grotesque animals often took the place of foliage, but seldom, as heretofore, mixed with foliage. The beautiful richness of foliated surfaces, so charmingly begun in the Norman, was completely lost.

However closely we endeavour to trace the origin of Decorative Art, we find that it constantly originated in forms taken from Natural Foliage. No doubt simple cutting, or notching with a knife or other sharp tool, preceded the imitation of natural form, and for this reason the zigzag and its simple combinations were the earliest forms of ornamentation invented by man. The zigzag is found in the primitive work of nearly all nations — shewing that it was the first natural step in the attempt at ornamentation although no people ever developed its capabilities so much, or adhered to it so long, as the Normans. As soon as tools improved, and primitive workmen felt they were able to go beyond simple notches, they began to imitate natural objects ; and consequently the most simple leaves and flowers which were growing around them, as well as the forms of the animals with which they were familiar, were soon rendered by them and adapted to the decoration of their works. Now as this facility of imitation varied among different people, so their renderings from nature varied; and as early artists also copied from one another, these diverse manners of following nature became more confirmed and stereotyped as time advanced. Thus arose that highly conventional treatment of natural forms which appears so conspicuously in early works, giving great distinctness of character, and shewing marked difference in the manner of rendering even the same natural objects by various nations at different periods in the world’s history. p. 24

….in the transitional piers at New Shoreham church the abacus is round, and the foliage begins to assume the Early English type p.55 James Kellaway Colling F.R.LB.A., (1874) Examples of English Medieval Foliage and Coloured Decoration, Taken From Buildings Of The Twelfth To The Fifteenth Century: With Descriptive Letterpress. B. T. Downloadable at https://archive.org/details/examplesofenglis00coll, retrieved 10.12.25

The choir of St Mary de Haura is a riot of vegetation; a paradigmatic example of the importance of vegetation in Romanesque (C11-C12) churches; before vegetation was replaced by other imagery in the Perpendicular period.

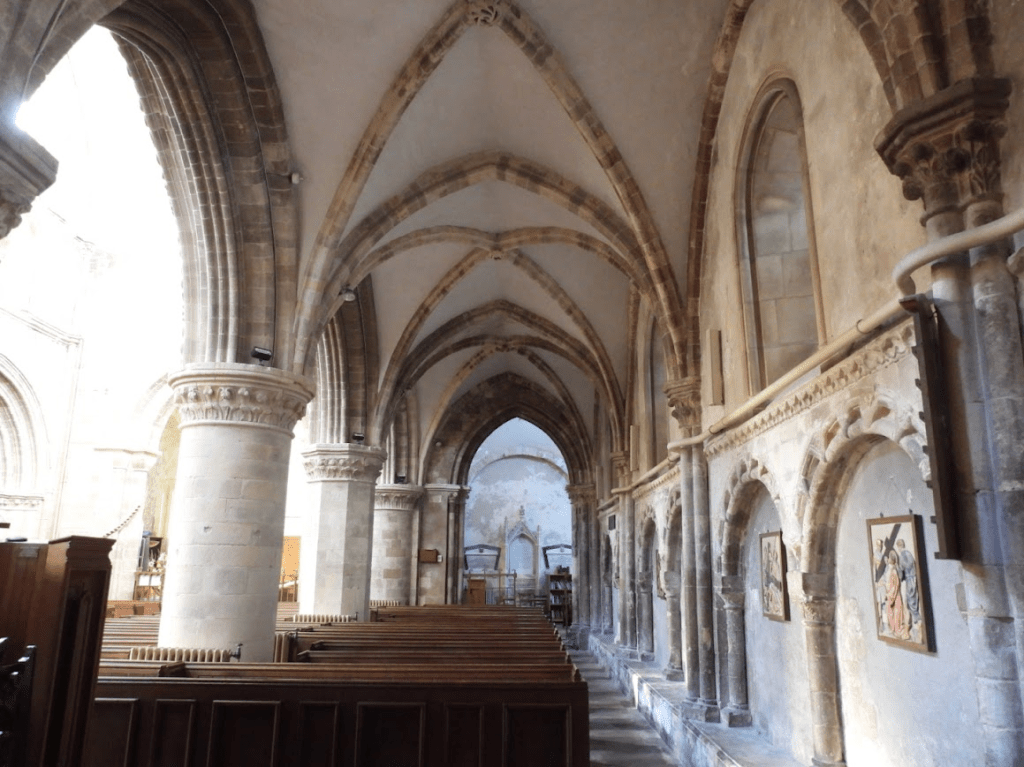

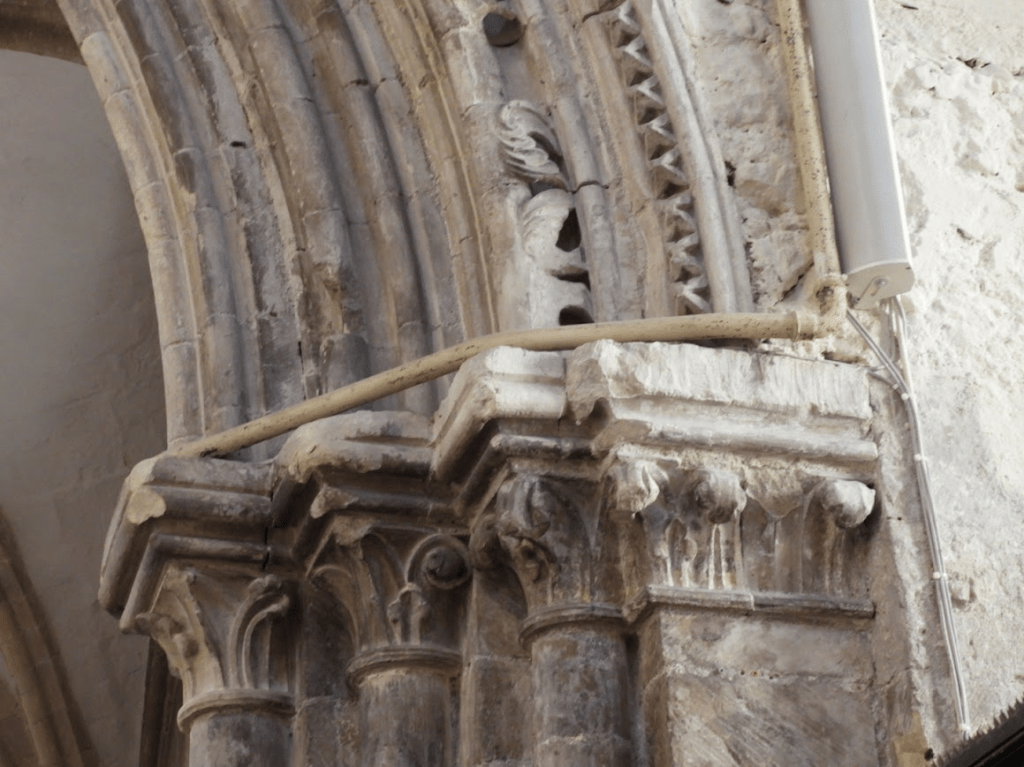

The quadripartite aisle vaults, with roll-moulded ribs and small foliage-bosses (including three with a green man in the south aisle), may have been complete before the upper parts [of the church] were started. … The triple shafts on the outer walls, with stiff leaf capitals, also look late C12 and are closest to the lower parts of the arcades. The stiff leaf capitals on the alternating round and octagonal piers of the north arcade, with an outer order of foliage, recall Canterbury. Either they were the work of masons from there or there was influence from Chichester, where Canterbury masons are known to have worked… The mouldings of the pointed arches are finer than those of the south arcade, where the piers have clustered shafts, each with a stiff leaf capital. The innermost ones rise to the vault and, as the date differs little from the north arcade, despite the differences, are further confirmation that a vault was intended from the start.

The variation of forms characteristic of New Shoreham is most evident in the gallery, beneath which is a continuous band of quatrefoils that does not vary. Earliest are the single eastern bays on the north side, which have moulded trefoiled heads and shafts with more stiff leaf. The remaining three bays have double openings. Like the openings of the south side, they have hook-corbels at the outer corners. These are a New Shoreham characteristic; not perhaps the happiest of designs, it is commoner in Normandy than England. Here, they contrast with the inner capitals, which have foliage, and there are two more at the springing of the vaulting shafts on the north side. Sussex Parish Churches Mary de Haura, New Shoreham, retrieved 02.12.26

A quatrefoil is a symmetrical design with four overlapping, leaf-like lobes, resembling a four-leaf clover or a four-petal flower, derived from Latin for “four leaves”. Popular in Gothic architecture for windows and tracery, it symbolizes good luck, harmony, and the four Gospels in Christianity, appearing in art, heraldry, and luxury goods globally, from ancient Islamic art to modern fashion. In Christianity, the symbol was adopted to represent the four gospels of the bible: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, as well as also seen as a representation of the cross. In Native America, the quatrefoil is a representation of their ‘Holy four corners of the Earth- North, East, South and West’ Quatrefoils: A Closer Look at this Superb Architectural Element accessed 04.01.26

The leaf capitals of the componde columns of the choir

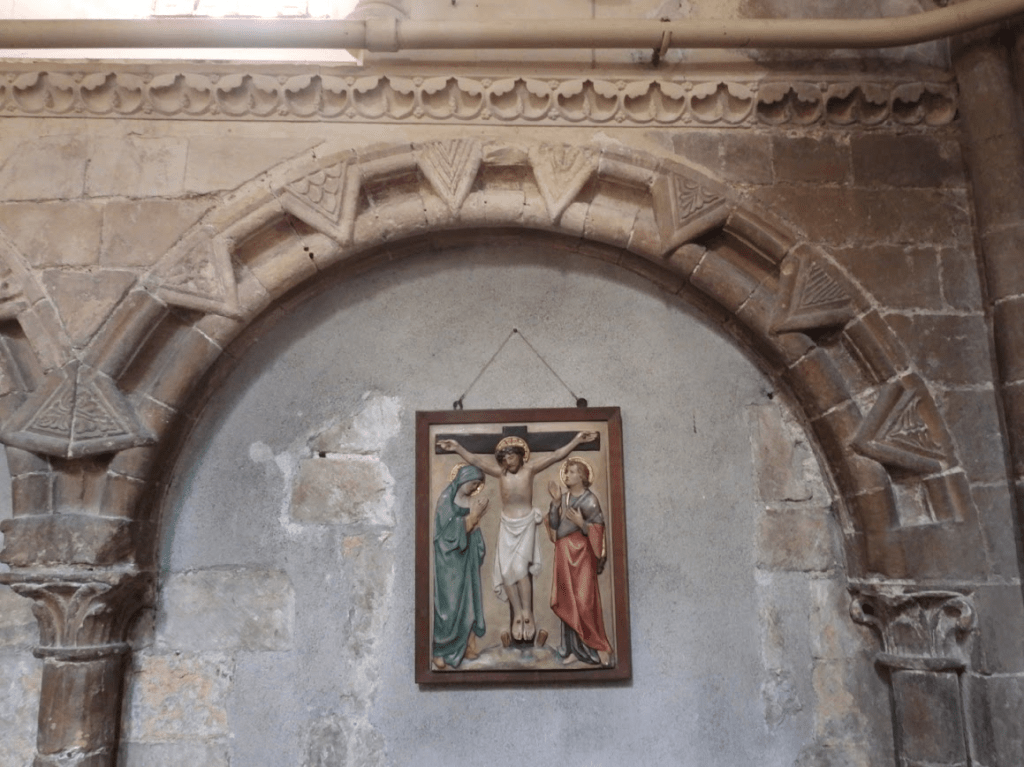

The blind arcade of arches (arches against a wall – decorative rather than structural) decorating the south wall of the choir (a typical feature of Romanesque architecture).

The voussoirs (wedge-shaped stones) of the blind arches are decorated with leaves – but each one leaf is different; showing remarkable creativity by the

Examples of leaf vosiers

The frieze across the blind arcade of the choir is also foliate

The capitals of piers of north arcade some round, some hexagonal, show a rich variety of geometrical foliage, as do the arches that the piers support.

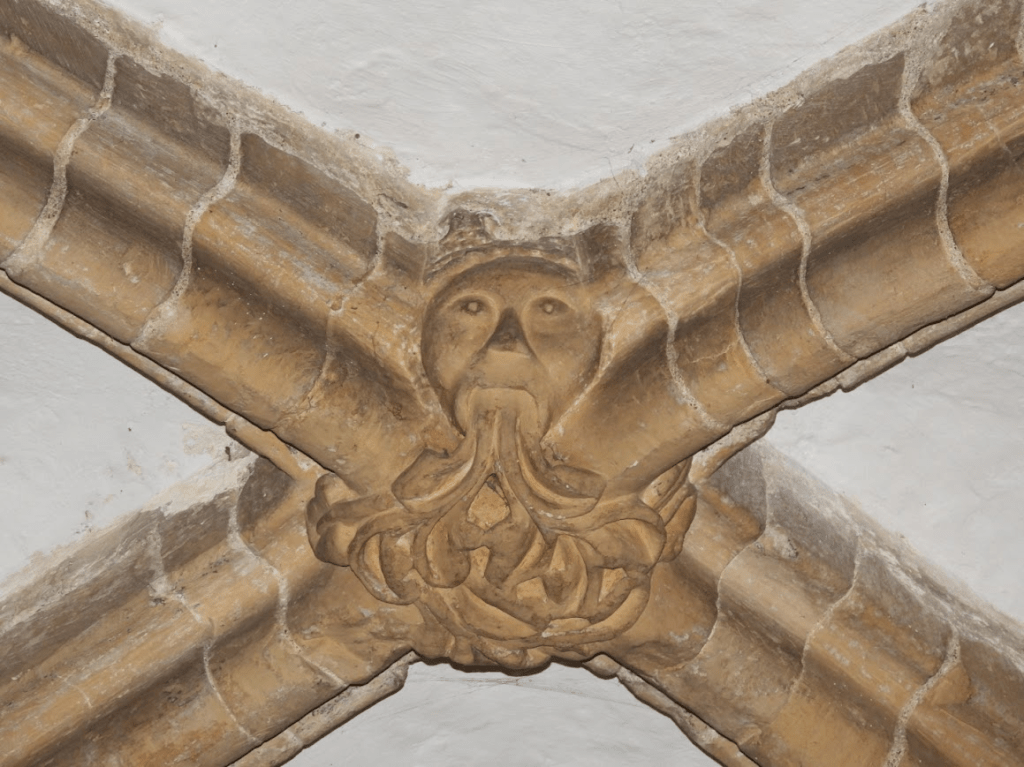

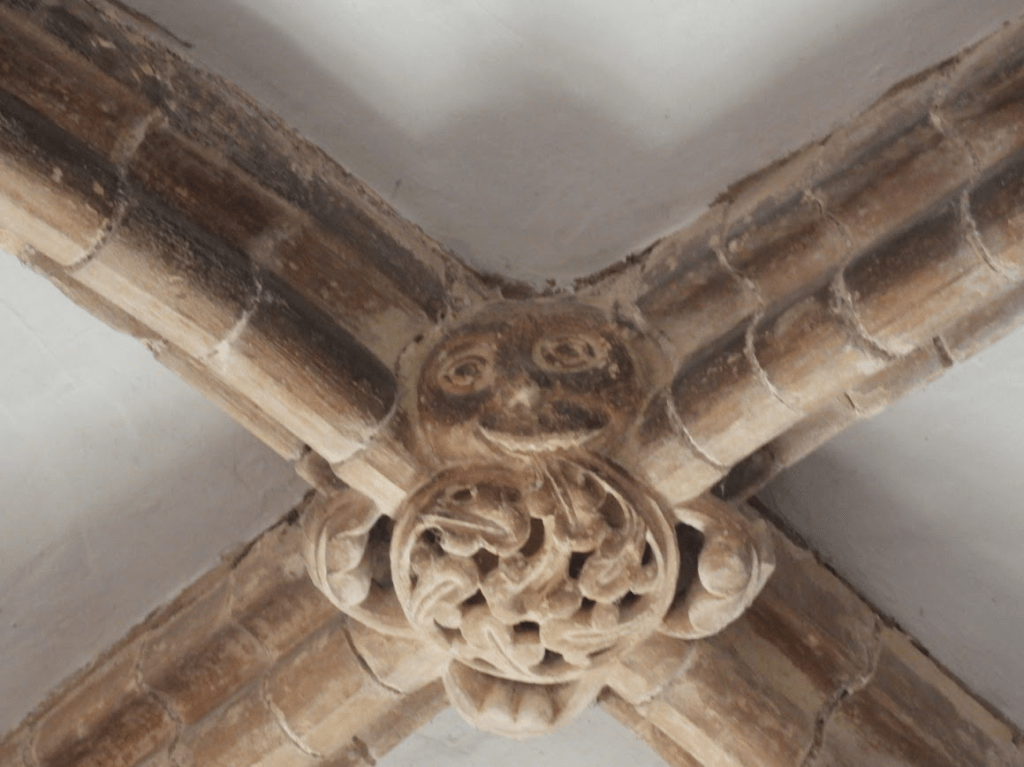

Two of the bosses of the ribbed vault of the south aisle of the nave are decorated with foliated head (often called Green Men)

Green Men stir deep associations with the land and pre-Christian pagan worship of nature, but to use the phrase Gredn Men to describe these bosses is historically anachronistic as the label was coined by the folklorist Lady Raglan, Julian Somerset, in her 1939 article, “The ‘Green Man’ in Church Architecture.” Folklore, vol. 50, no. 1, 1939, pp. 45–57. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1257090. Accessed 4 Jan. 2026.

Whilst I would love to believe that foliate heads demonstrated a persistence of pagan beliefs (fertility cults etc.) in Christian spaces; I think it is much more likely that masons thought of foliate heads as Christian symbols. Kathleen Basford, a botanist and folklore historian, in 1978 book, The Green Man – the first academic monograph of Green Men – suggests that foliate heads had previous pagan symbolic significance; but when used in churches it is likely that foliate heads symbolize Christian themes. They represent a sort of vernacular Christianity according to Stephen Winick, a folklorist at the American Folklife Center of the Library of Congress, who suggests, in The Green Man, Vernacular Christianity, and the Folk Saint (Library of Congress blog 2022) accessed 04.01.23 that foliate heads symbolize the rebirth of Christ and the promise of eternal life; connection to the Tree of Life growing from Adam’s mouth and life’s cycle: the continuous cycle of nature, death, and renewal. Winick notes that more general sense, the idea of greenness, verdure, or viriditas has been part of Christian philosophy at least since the writings of Gregory the Great, specifically his treatise Moralia in Job, circa 580-595 CE. As Jeanette Jones has shown, Gregory posits greenness (viriditas) and plant growth in the book of Job to be a metaphor for the coming of Christ. It is probably this notion that underpins the use of green foliate ornamentation in Norman churches.

Foliate capitals of the quadripartite pillars supporting the cross of the choir, aisle and transects; thick so they can old up the tower above. Highly complex foliate forms made possible by the function of pillars: weight bearing.

The south side of the Norman font depicts stars, another aspect of the natural world. English Romanesque, Norman, architecture and art is known for its robust construction and distinctive ornamentation, including geometric patterns like the zigzag (chevron) and stars or rosettes.

But perhaps these are more than just patterns? Patterns are seen on the doorways of village churches, throughout greater churches and in secular buildings. Pattern-making was typical of traditional art, while geometry, symmetry and order were considered by theologians to reflect heavenly perfection. It is suggested that geometric patterns, sometimes described as rosettes, diaper, zigzag, scale and arcading, were used in English Romanesque sculpture in a coherent series to build up a cosmographic diagram. The comprehensive building programme that followed the Conquest allowed the language of geometric patterns to be used more intensively in England than appears to have been the case on the Continent. Wood, R. (2001). Geometric patterns in English Romanesque sculpture. Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 154(1), 1-39. Abstract

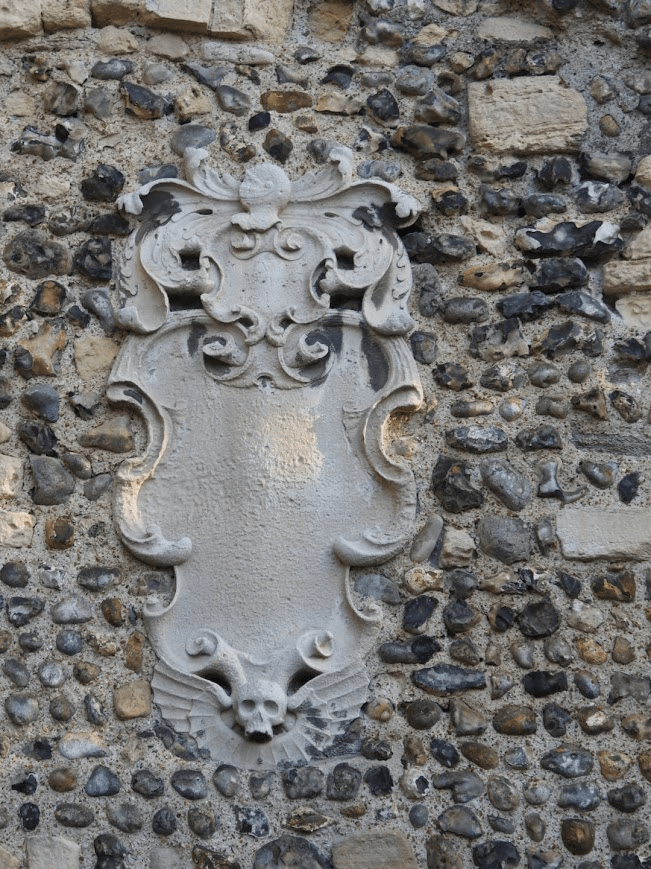

Whist foliage in the broadest sense symbolises life, in contrast, a memorial plaque (cartouche), on the west exterior wall of the church, signifies bodily death. The name of the person memorialised has eroded away by the salty westerly winds of the Channel. But its baroque style and the helmet suggest that this is a memorial to a now unknown C18 peer of the realm