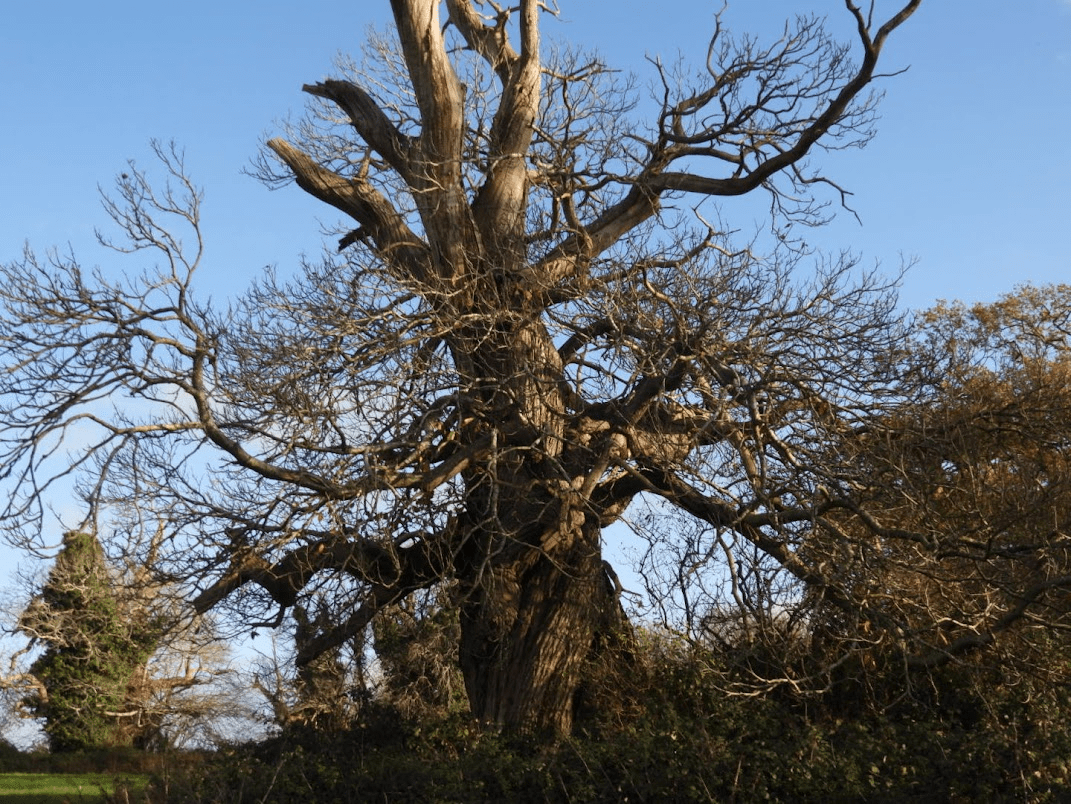

On a recent trip to the parish of Boxgrove, I walked up the footpath to the west of Halnaker Park, an ancient deer park. Most deer parks have mostly pollarded Oaks, but this one has mostly Sweet Chestnuts. Some other deer parks have Sweet Chestnuts too; such as Bushy, Richmond and Petworth; but in these Oaks domiate; at Halnaker Sweet Chestnut dominates. The Sweet Chestnuts in the park are magnificent; but close-up examination of those by the path revealed them to be in a parlous state.

My description of the other features of Boxgrove Parish, including the magnificent Boxgrove Parish Church, see Boxgrove Parish’s historic landscape & built environment; focusing on the painted & carved foliage in Boxgrove Priory Church of St Mary and St Blaise. 28.11.25

The Park of Halnaker possibly originated in a grant of free warren made in 1253 to Robert de St. John for his demesnes at Halnaker, Goodwood, and elsewhere, outside the limits of the forest. An inquiry as to the recent enlargement of the park by 60 acres was ordered in 1283, and it was said to contain 150 acres in 1329, and to be 2 leagues round in 1337. Hugh, elder son of Lord St. John, had licence in 1404 to inclose 300 acres of land and wood within the lordship of Halnaker and make a park, according to the metes begun by his father, but possibly did not avail himself of it, as the licence was renewed to Thomas and Elizabeth West in 1517. This may be the origin of Goodwood Park, which first appears in 1540, when it was part of the Halnaker estate, as it was also in 1561. In 1570 Halnaker Park was estimated to be 4 miles in compass and supported 800 deer. It continued to descend with the manor, but Goodwood Park was sold in 1584 by Lord Lumley to Henry and Elizabeth Walrond, who transferred it in 1597 to Thomas Cesar; he conveyed it in 1599 to Thomas Bennett, who in 1609 sold it to Sir Edward Fraunceis. The Earl of Northumberland in 1657 sold it, with ‘the house lately erected therein’, to John Caryll, who conveyed the park and mansion house to Anthony Kempe in 1675, and it subsequently came to the Comptons of East Lavant, from whom it was bought, about 1720, by the Duke of Richmond. from: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/ Quoted on https://boxgroveparishcouncil.gov.uk/about-boxgrove/halnaker/#:~:text=The%20PARK%20of%20Halnaker%20possibly,fn.

The importance of ancient deer parks is outlined in the University of Oxford’s Ancient Oaks of England Project Deer Parks: After the Norman conquest of England in 1066 deer parks became a ‘craze’ among the new nobility, who had taken over almost all the land held before by the Anglo-Saxons. While the Domesday Book in 1086 only recorded 37 deer parks, by around 1300 there may have been as many as 3,000. Every nobleman wanted a park and many had one, while great magnates and some bishops owned 10 or more and the king could boast as many as 80 to 100. It was all about hunting deer and having venison available for feasts. To be able to present guests with this ‘noble’ meat instead of the plain beef and pork that common people (sometimes) had was a serious matter of status.

A deer park was usually created in an area of the manor that was not under cultivation or occupied by hayfields or woods managed as coppice. It was called ‘waste’ (we would now say nature reserve) and often consisted of some open rough grassland or heath and pasture woodland. There were wild growing native trees, mainly oaks. These and some underwood or shrubs were necessary to provide for winter food and shelter. This became especially important with the introduction by the Normans of fallow deer from southern Europe to stock the parks. These animals would not survive the English winter otherwise.

The park was surrounded by a park pale, a ditch on the inside and an earth wall on the outside on top of which was a pale fence of cleft oak. The deer could not scale such a barrier from inside the park, but ‘deer leaps’ could lure them in from outside, a clever construction. … Also inside was usually a park or hunting lodge and if this building was moated we can often still recognize this moat as well as lines of the park pale in the form of lanes, field boundaries or even the earth wall of the park pale. We now know where most of these parks were even if few of these traces remain. By analyzing the position of ancient oaks in the landscape we can find out if they stood in a medieval deer park.

My research has established that medieval deer parks were by far the most important form of land use associated with ancient and veteran oaks in England. Some 35% of all oaks in England with a girth >5.99 m are associated with medieval deer parks and of 115 oaks with >9.00 m girth 60 once stood in those ancient deer parks. Of 23 ‘most important sites’ for ancient oaks I have so far identified, 20 were deer parks and 16 of these were medieval. There are many other landscape associations with ancient oaks and for a significant number of these trees the historical context remains unknown, lost in the mists of time. But the medieval deer parks are the main reason why England has so many of these venerable oaks. https://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/ancientoaksofengland/Deerparks

Typical location [of Sweet Chestnut]: Parkland, designed landscapes, fields, woodland (often found as coppice) and wood pasture. Occasionally avenues, street trees and gardens. Age: Sweet chestnut may be able to live for 1,000 years, although 600 may be more typical on many sites. All sweet chestnut will be ancient from 400 years onwards, although many will have ancient characteristics from around 300 years. Woodland Trust Sweet Chestnut

Jarman identifies seven types of British ‘sweet chestnut landscape’: ancient inclosures; ancient coppice woods; historic boundaries; historic gardens; historic deer parks and designed parklands; historic formal avenues; and more recent high forest and production coppice. R.A Jarman (2019) Sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) in Britain: a multi-proxy approach to determine its origins and cultural significance; unpublished PhD Theses. University of Gloucester. https://eprints.glos.ac.uk/7484/1/Robin%20Jarman%20PhD%20Thesis%20Sweet%20chestnut%20in%20Britain.pdf retrieved 01/12/25 p. 2

Sweet Chestnuts Outside of woodland habitats, sweet chestnut performs a different ecological role, as in wood pastures and historic parklands, where stands of single or groups of ancient trees, stubs and stools support many veteran tree features (Lonsdale, 2013). Such trees sustain a wide diversity of scarce and sometimes endangered invertebrate and other animal species; and host a specialised flora, notably lichens, bryophytes and fungi. These trees and their associated communities are typically many centuries old and provide sites of high ‘ecological continuity’ (Rose, 1974 and 1976) in landscapes where these are rare. Johnson op. cit. p. 45

In that context of ecological continuity and antiquity, cultural significance is not a separate concept – humans can be considered as part of nature, and the ‘sweet chestnut scapes’ that were discovered and surveyed during this research reflect that: ancient inclosures, ancient coppice woods, historic boundaries, historic gardens, historic deer parks and designed parklands, historic formal avenues, and high forest and production coppice are all artefacts of management. Johnson op. cit. p.47

The Sweet Chestnuts in Halnaker Park are ca. 400 years old; they look very unlikely to make it to 600 years, let alone 1000 year.

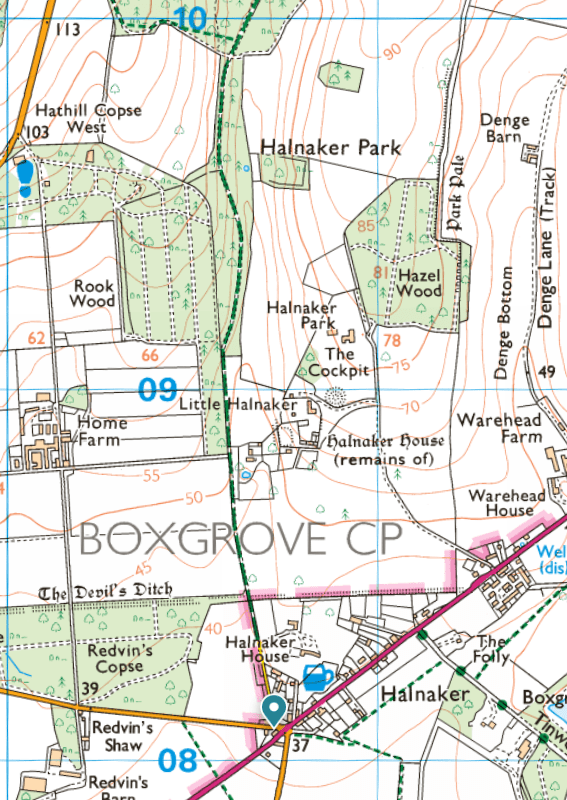

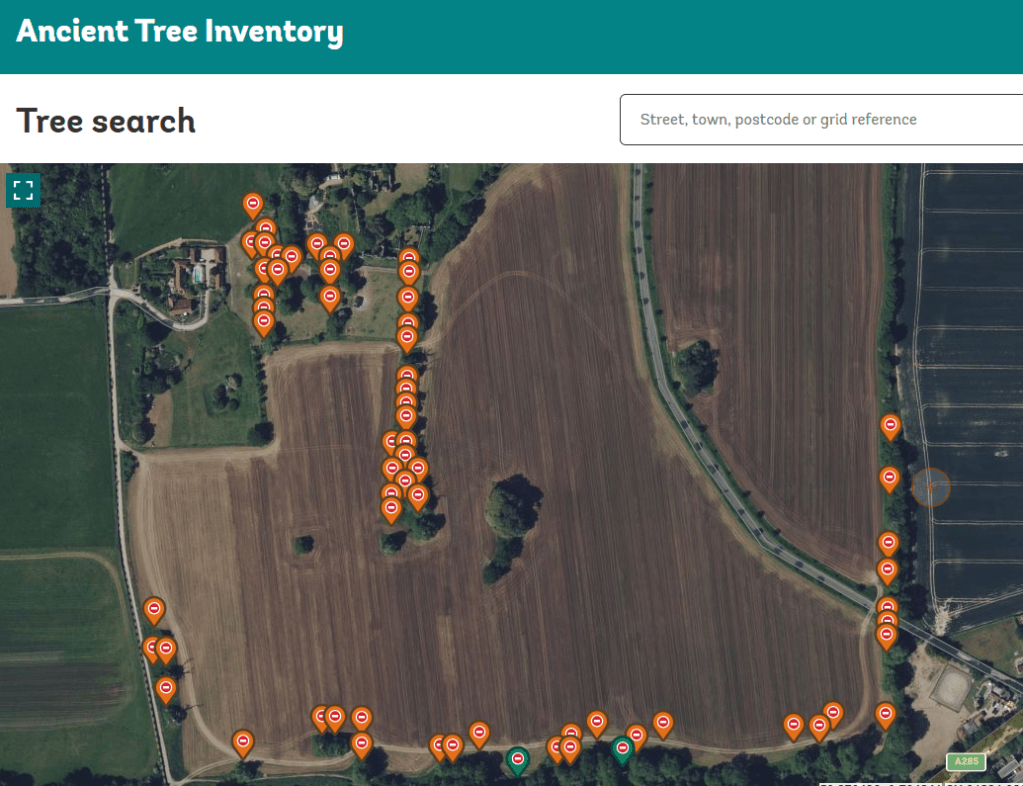

The Sweet Chestnuts are listed by the Woodland Trust Ancient Tree Inventory as all ancient.

Map: Woodland Trust Ancient Tree Inventory

They are pollarded, as was typical for trees in deer parks. These ancient Sweet Chestnuts are one of the most important natural assets of the parish of Boxgrove, West Sussex. These Sweet Chestnuts are biologically important and a benefit to the landscape.

(The 18th, 19th and 29th century practice of replanting semi natural ancient woodland with Sweet Chestnut, which was then coppiced for timber, was not a benefit to landscape of Sussex; but it was profitable.)

From Parks & Garden UK: Halnaker Park

(Parks & Gardens UK is the leading online resource for historic parks and gardens. It is an essential resource across multiple fields, from heritage preservation and academic research to personal enrichment and professional garden design).

The most impressive feature of the landscape [of Halnaker] is the mature Sweet Chestnut Trees. In essence, the landscape of Halnaker Park has changed little in 370 years, with the exception of changes in land use. More of the park is now under arable cultivation rather than grassland and pasture (as indicated by the field names in 1629). …

The most impressive feature of the landscape is the mature Sweet Chestnut Trees. There are 74 in total distributed along the lower southern boundary, in a block to the south-west of the ruins, in a long row to the south-east of the gate house entrance, and as isolated trees in the lower park. The trees are all in a poor state, with die back and bark loss. They are clearly very old. One has a girth of more than eight meters. ….

… [T]he names and location of woodland blocks in 1629 are similar to the current situation, that is: Haflewoode coppice (1629) = Hazel Wood Winkinge Woode = Ladys Winkins; Hoke Woode = Rook Wood; Harthill Wood = Hathill Copse West; Saley Coppice = Seely Copse

The gap or ride through the woodland to the northern boundary, apparent on maps of 1778, 1813, 1880 is still evident as Halnaker Gallop. The shape of the woodland blocks are almost identical to the 1880 map and very similar to the 1778 map. Many of the parkland trees and clumps on the 1880 map are still present today.

In essence, the landscape of Halnaker Park has changed little in 370 years, with the exception of changes in land use. More of the park is now under arable cultivation rather than grassland and pasture (as indicated by the field names in 1629).

The greatest threat to the historic landscape in the short term is the loss of the Sweet Chestnuts in the lower park. All the trees are showing signs of severe stress mainly due to agricultural activities, for example spray drift, ploughing too close to the tree base, or ring barking due to mechanical damage from equipment.

Returning the lower park to permanent pasture would reduce the stress on the trees and considerably enhance the setting of the ruins of Halnaker Park. https://www.parksandgardens.org/places/halnaker-park

This has not be done. The Lower Park is owned by the Goodwood Estate. All of the chestnuts are on their private land and there is no permissive access.

It is possible that the Goodwood Estate has not taken seriously the preservation of the precious natural assets of the Chestnut-planted deer park because of a prejudice against non-native trees, but as Jarman, et al., point out in (2019) Landscapes of sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa) in Britain – their ancient origins. Landscape History, 40(2), pp.5-40, there is a general consensus on the ecological importance of sweet chestnut in Britain. It can be concluded that, irrespective of whether it is ‘native’ or ‘alien’, the species performs an important ecological function in specific types of ancient semi-natural woodlands, notably in southern Britain where it does behave like the ‘honorary native’ that Rackham (in Rackham, O. (1980). Ancient Woodland) observed it to be. Johnson op. cit. p.47

What the Goodwood Estate says about stewardship: Nestled in the heart of rural West Sussex, the Goodwood Estate spans 11,000 acres, and has a great responsibility to protect, maintain and enhance its distinctive character and landscape. Ensuring that future generations can cherish Goodwood as we all do today.. Goodwood Sustainability

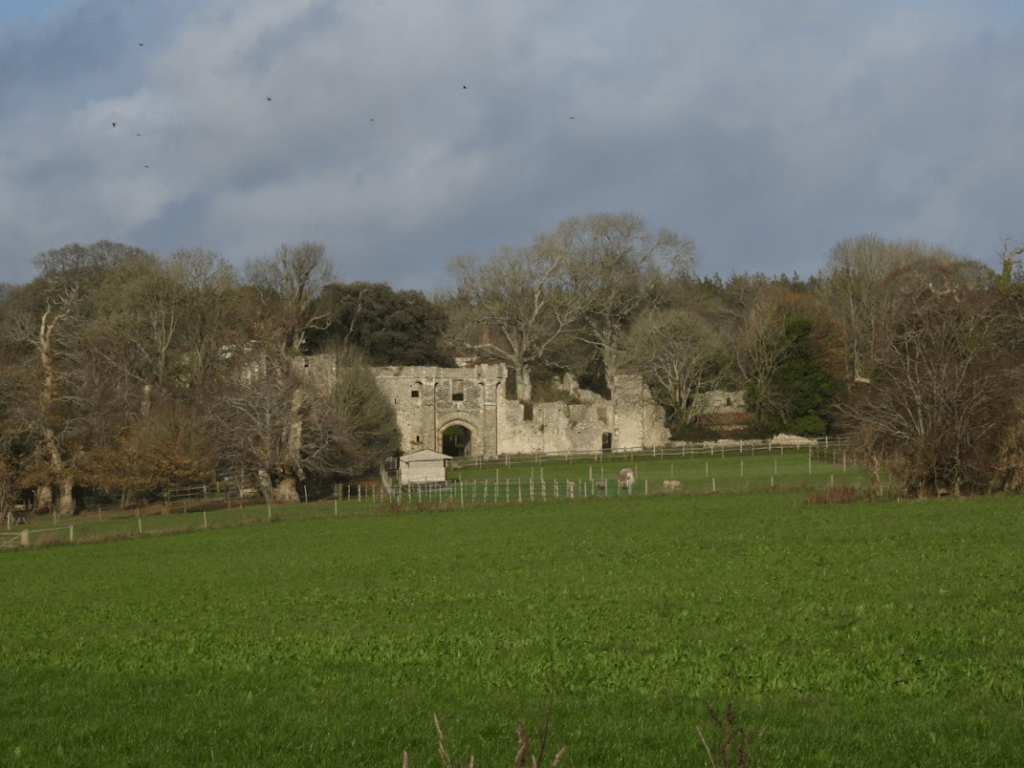

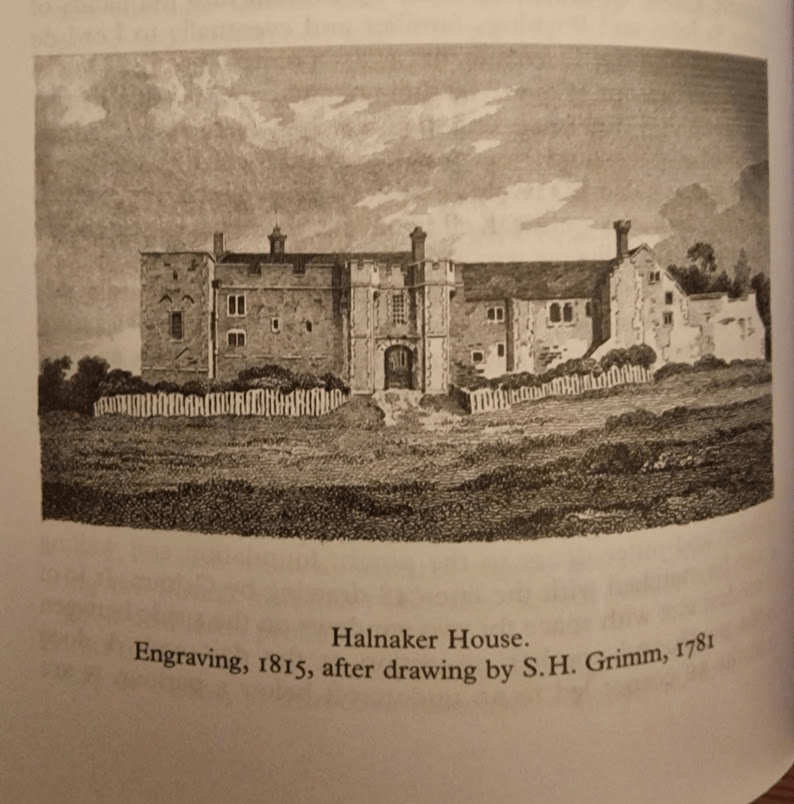

To the north are the remain of Halnaker House, again private with no permissive access. From Elizabeth Williamson, Tim Hudson, Jeremy Musson, Ian Nairn, Nikolaus Pevsner (2019) Sussex: West (Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England) pp. 409-401:HALNAKER HOUSE (ruins). Halnaker and Cowdray (q.v.) have remarkably similar history. Both were medieval houses given a wholesale remodelling in the C16 by owners who used up-to-date Renaissance ornament. Both became ruined about 1800. But where Cowdrav still impresses as architecture, too much has gone at Halnaker to make it more than a pretty, picturesque group of walls. This is not only the fault of the weather. Details were transplanted wholesale to Chichester, … It is a pity, for the complete Halnaker would have been very impressive.

It was begun by the de Haye family, the founders of Boxgrove Priory and came by descent into the hands of the St John and Poynings families and eventually to Lord de la Warr. The site faces south at the exact point where the Downs begin to rise out of the coastal plain, and consists of an irreg-lar retaining wall enclosing separate hall and chapel ranges. Closed at the south end by a nearly symmetrical C14 gatehouse and wings, achieving a semi-fortified, semi-regular effect which suited both the political climate and the visual inclinations of the C14. Halnaker was the type of Stokesay, not Bodiam. In the C16 the hall range was extended by a solar range that linked it to a chapel: work mainly done for Thomas West, Lord de la Warr (of the Renaissance chantry at Boxgrove and the Renaissance tombs at Broadwater …). The house became redundant when Goodwood was built but was not fully abandoned until the C19.

1781

2025