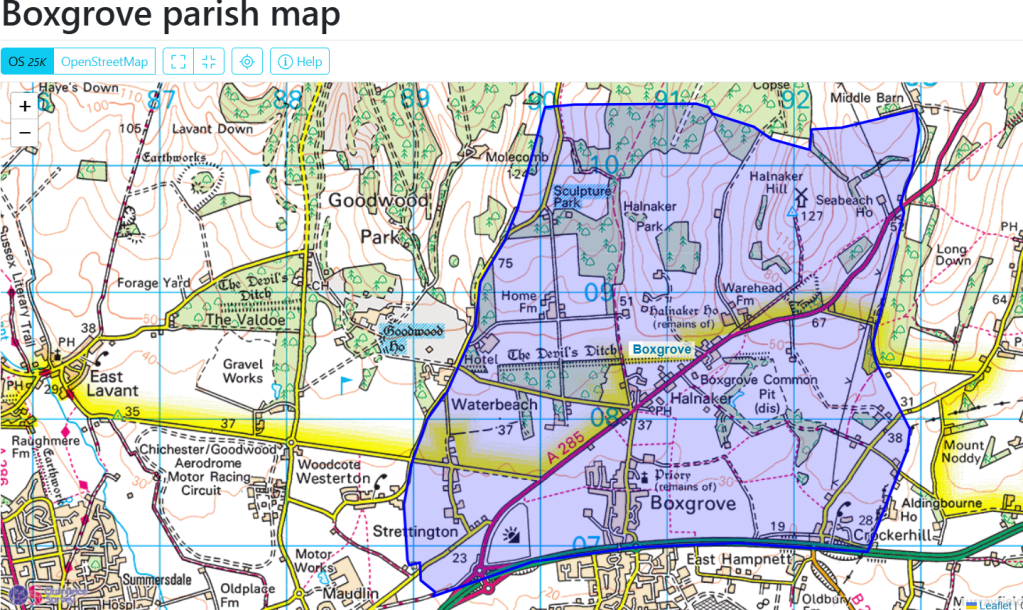

When you walk around the parish of Boxgrove, West Sussex, history collides in the landscape and the built environment; with extraordinarily diverse and interesting physical evidence of building and other human activity from the Neolithic, Iron Age, Roman Occupation, Norman, Plantagenet and Tudor periods.

The landscape of the Downs, itself formed by human activity – human introduced sheep grazing – is stunning beautiful; as are the ancient chestnuts of the Halnaker medieval Deer Park (which gets its own post). The importance of sheep to the creation of the South Downs, and the medieval economy of Sussex, is referenced in the name of the Boxgrove Priory Church: St Blaise is the patron saint of wool carders.

Sheep were vital to the medieval economy of Sussex, providing the primary raw material for the region’s thriving wool and cloth industry, which was the backbone of the national economy. Beyond wool, sheep provided other valuable resources like meat, milk, and manure, and their management was integral to the agricultural practices that made the area one of the wealthiest in England. P.F. Brandon (1971) Demesne Arable Farming in Coastal Sussex during the Later Middle Ages Agricultural History Review

The pinnacle of its built environment is the Plantagenet and Tudor Boxgrove Priory Church with the De la Warr Chantry being of international art historical importance.

It is a magical church full of echoes of French influence along the Sussex coast. Its crossing is a mystery of light and dark and the great chancel is alive with Tudor roses and heraldry. The De La Warr chantry contains beautiful early French motifs from a Book of Hours. These must be some of the best renaissance carvings in any English church. They make Boxgrove very special. Sir Simon Jenkins

There are later building of historical importance too, specifically the 18th century tower Wind Mill on Halnaker Hill (1740) and Sir Edwin Lutyens’s Halnaker Park, built in 1938.

From the Saturday Walkers Club maps

On Halnaker Hill is a neolithic (10000 BC – 2200 BC) causeway enclosure. Below Halnaker Hill. is the late Iron Age Devil’s Ditch; it dates probably from the late Iron Age (ca. 100 BC – AD 43). The Ditch terminates where it meets Stane Street. The Roman Stane Street may have been built shortly after the Devil’s Ditch in the first decade of the Roman occupation of Britain (as early as 43–53 AD). There was an Anglo-Saxon church at Boxgrove (recorded in the Doomsday Book) but there are no physical remains of it. Over it was built an early Norman Benedictine Priory, completed ca. 1170.; its nave is now ruined but the Priory Church of St Mary and St Blaise remains, with the addition of a C14 porch and a C15 vestry, and the addition of outstandingly beautiful C16 C De la Warr chantry (ca 1530).

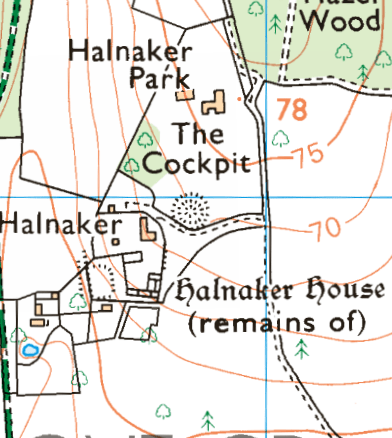

In the north of the parish of Boxgrove is the Halnaker medieval deer park (grant of land 1283.) with the ruins of the C14-C15 fortified Manor House of the De La Waar family. A very noticeable feature of the landscape is the outstanding cluster of ancient Sweet Chestnut trees in the medieval deer park and the ruins of Old Halnaker House built by the de Haye family in the thirteenth century, see The degradation of the ancient Sweet Chestnuts trees of Halnaker Park, due to change of land use from pasture to intensive arable farming. 28.11.29 for more on the chestnuts and the house.

simelliottnaturenotes.blog/2025/12/01/the-degradation-of-the-ancient-sweet-chestnuts-trees-of-halnaker-park-due-to-change-of-land-use-from-pasture-to-intensive-arable-farming-28-11-29/

Ruins of the De Lar Warr Manor House

House Sweet Chestnut

One of the ancient Sweet Chestnuts; now is very poor condition.

Halnaker Hill’s Windmill from the Deer Park – in this perspective its looks dwarfed by the ancient Sweet Chestnuts!

A fascinating man-made feature of the parish is the octagonal reservoir in the Halnaker House. This is not accessible publicly. The OS map calls it a cockpit; but it may not have been.

Photograph from Historic England

A later and important part of the landscape is house of Sir Edwin Lutyens, built in 1938, see Historic England Halnaker Park but this listed building is invisible from roads and public footpaths and is hidden from view by the trees of the medieval deer park in which it is located; and it is private.

Lutyen’s Halnaker Hall, photo by Robert Palmer on Historic England listing on-line

The occasion of the Second World War added to the historic melange of Boxgrove Parish’s Halnaker Hill concrete and octagonal brick structures which formed the base of searchlight emplacements. All that remains of these structures is parts of the bases; this are particularly ugly but are of historical importance and are listed by Historic England However, the brick and concrete does provide a substrate for some beautiful lichens e..g the very common Lecanora campestris which I photographed there on 07/12/2024

There are some interesting sixteenth to nineteenth century vernacular houses in the parish; these are excellently described, with photographs, by John Bennett and Beryl Bakewell, available at January 2021 – Boxgrove and Halnaker Listed properties

Halnaker Hill Causeway Enclosure

The oldest feature of the landscape is the neolithic Causeway Enclosure on the top of Halnaker Hill, close to the Halnaker Mill. Between 50 and 70 causewayed enclosures are recorded nationally, mainly in southern and eastern England. They were constructed over a period of some 500 years during the middle part of the Neolithic period (c.3000-2400 BC) but also continued in use into later periods. They vary considerably in size (from 0.8ha to 28ha) and were apparently used for a variety of functions, including settlement, defence, and ceremonial and funerary purposes. However, all comprise a roughly circular to ovoid area bounded by one or more concentric rings of banks and ditches. The ditches, from which the monument class derives its name, were formed of a series of elongated pits punctuated by unexcavated causeways. Causewayed enclosures are amongst the earliest field monuments to survive as recognisable features in the modern landscape and are one of the few known Neolithic monument types. Due to their rarity, their wide diversity of plan, and their considerable age, all causewayed enclosures are considered to be nationally important. Historic England Causeway Enclosure, World War II searchlight emplacements and associated remains on Halnaker Hill

LIDAR image of the Causeway Enclosure, posted by Grahame Hawthorn on the posts and comments of the Historic England website

Devil’s Ditch

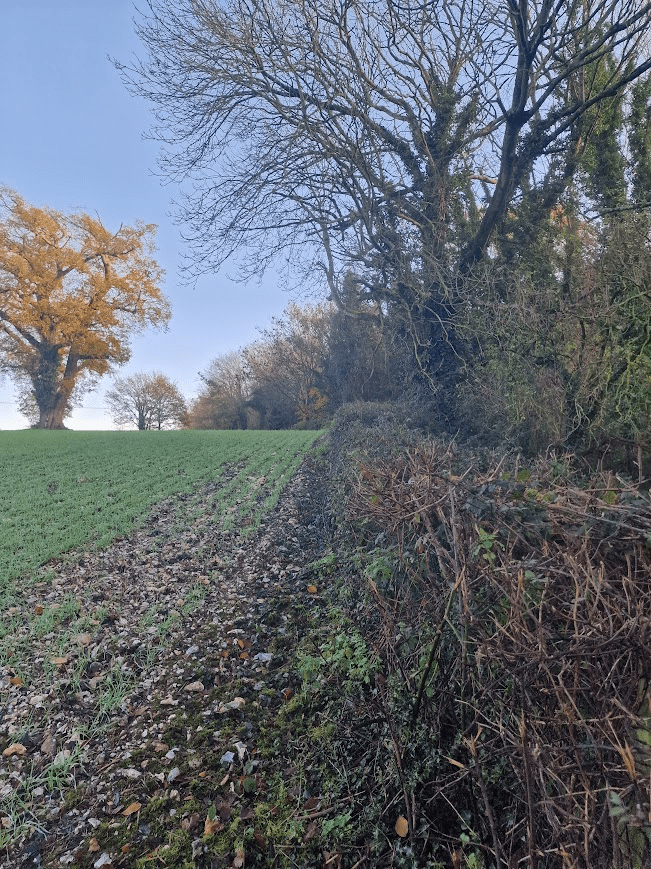

The Devil’s Ditch consist of a banked ditch, the bank being wooded mostly with Pedunculate Oak and Field Maple

The Devil Ditch forming the south boundary of the Halnaker Deer Park:

Butchers Broom in the ditch.

The bank and ditch of the Devil’s Ditch is continuously wooded mostly with Pedunculate Oak and Field Maple. Butcher’s Broom is an ancient woodland indicator species ; so the Devil’s Ditch has biological importance as well as historic importance,

The earthwork is denoted by a bank and a ditch, which grows fainter as it heads east. It runs west to east, forming a boundary at the northern edge of Redvins Copse, passes north of Oak Cottage and Stanefield house before it ends at Stane Street Roman Road. At the eastern end it forms the southern boundary to Halnaker Park. Towards the western end, the bank is about 2.5m above the bottom of the ditch, which is about 6m wide. At the eastern end, near Stane Street, the ditch is wide and shallow indicating that it may have been recut at a later date and possibly used as an early trackway.

The Devil’s Ditch in Sussex has been documented by antiquarians since at least the 18th century. It is part of a group of linear earthworks on the gravel plain between the foot of the South Downs and Chichester Harbour. The entrenchments run from Lavant to Boxgrove and appear to enclose the area of the coastal plain to the south. It has been suggested that these marked out a high status, proto-urban tribal settlement (or ‘oppidum’) preceding the Roman invasion. The Devil’s Ditch is thought to date to the Late Iron Age (about 100 BC – AD 43) but was recut and extended in places during the medieval period. The name of the entrenchment is derived from a local tradition, which holds that the ditch was the work of the devil in an attempt to channel the sea and flood the churches of Sussex. Historic England Devil’s Ditch, section extending 1730yds (1580m) from Stane Street to NW end of Redvin’s Copse

Stane Street and the Halnaker “Tree Tunnel”

Stane Street linked London (Londinium) to Chichester (Noviomagus Reginorum); and runs through the South Downs. Stane is an old spelling of “stone” (Old Norse: steinn) which was used to differentiate paved Roman roads from muddy native trackways. At Halnaker Hill, Stane Street becomes a “tree tunnel”; which is famed on social media, with may photographs like mine below. There are far better photos of the tree tunnel than mine; just Google Halnaker Tree Tunnel and you will see them. Whilst the Halnaker Tree Tunnel is beautiful, from my experience of walking in Sussex there are far more beautiful and historically significant sunken trackways (hollow-ways) in Sussex than this tree tunnel; but for some reason Halnaker Tree Tunnel has “gone viral”; which shows how social media can distort public attention to what is important in the country side.

Remains of the Priory

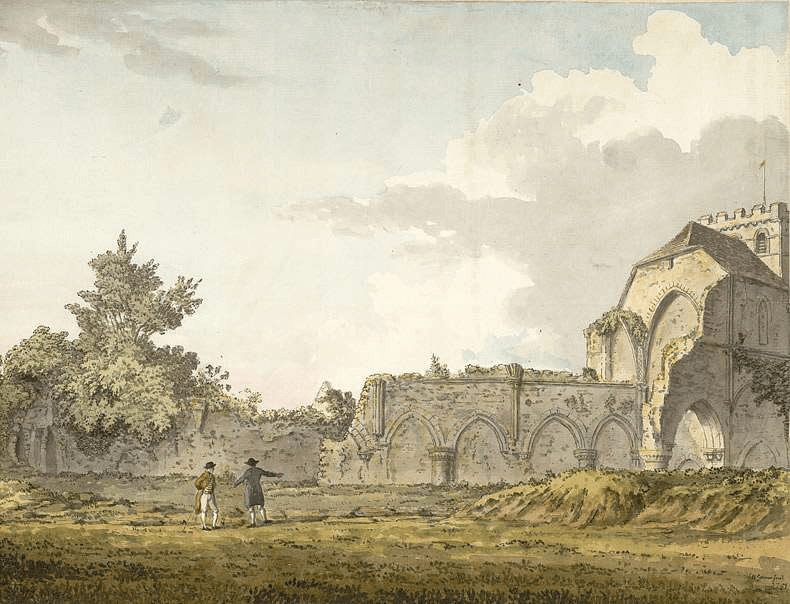

The small Benedictine priory of Boxgrove in West Sussex was founded in about 1107, originally for just three monks. In a beautiful setting at the foot of the South Downs, the principal remains include a fine two-storey guest house, roofless but standing to its full height at the gable ends. The eastern parts of the priory church became Boxgrove’s parish church after the Suppression of the Monasteries. English Heritage Boxgrove Priory

The importance of the ruins as a picturesque spectacle drew tourists, artist and antiquarians throughout the 18th and 19th century; perhaps enhanced by William Gilpin, who in the eighteenth century wrote essays that explored the picturesque as a new aesthetic concept

Starting in the 18th century, the history of the priory and its ruins attracted the attention of antiquarians and artists. The latter included Samuel and Nathaniel Buck, who in 1737 published an engraving of the church and surviving portions of the roofless monastic buildings. English Heritage Boxgrove Priory

Below, a watercolour view of the ruins of the nave of Boxgrove Priory, seen from the churchyard, by Samuel Hieronymous Grimm, 1781

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (18 January 1733 – 14 April 1794) was an 18th-century Swiss landscape artist who worked in oils (until 1764), watercolours, and pen and ink media. Grimm specialised in documenting historical scenes and events; he also illustrated books such as Gilbert White’s The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne. Tate Samuel Hieronymus Grimm

Priory Church of St Mary and St Blaise, Boxgrove.

For an in-depth history of the Priory and Priory Church see British History Online Boxgrove

The decorations by Lambert Barnard of the choir vault and the sculpture of De La Warr Chantry are of international art-historical importance.

On the choir vault there are decorations by Lambert Barnard for Lord de la Warr (Croft-Murray p112), probably linked with his chantry. Naturalistic foliage, interspersed with the arms of de la Warr and relatives. Sussex Parish Churches Boxgrove Priory Church. Lambert Barnard (d1567/68) did much work for Bishop Sherburn (1508-38), notably in Chichester cathedral. Little is known of his life, but stylistically, if not by birth, he had Netherlandish links. E Croft-Murray: Lambert Barnard: an English Early Renaissance Painter, AJ 113 (1957) pp 108-25 Sussex Parish Churches Architects and Artists B

It is hard to know what particular species the flowers depicted on the C16 ceiling painting, commissioned by Thomas West, the 9th Lord de la Warr, are intended to be. They are described as a “delightful mix” of various local plants; but I think it more likely that they are a symbolic representation of the importance of flora to Thomas Wests beliefs; with their decorative pattern being more important than close observation of actual flowers. Botanical accuracy in botanical art was a feature of 17th and 18th century still lives and botanical illustration for florae. The flowers on this 16th century ceiling were probably not meant to be accurate representations of local plants, even if they were inspired by them; they are more symbolic than representational. The symbolic religious use of flowers as symbols of God’s creation was common in medieval churches, as I reminder that all of creation praises God, and perhaps representing the Garden of God, Eden, or the beauty of heaven. Considering that 9th Baron De La Warr was expecting to be buried in this church, it is likely they he wanted them to represent his ascent into heaven.

The chantry in the choir was built by Thomas, Lord de la Warr for himself and his wife between 1530 and 1535 and led to a major internal alteration. … [A chantry is a chapel or area within a church where a priest who would say daily masses for the donor’s soul] The chantry is more a piece of architecture than a monument in any conventional sense. Ironically, … de la Warr was buried at Broadwater in 1554. This was probably because he fell out of favour and was compelled by the King [Henry VIII] to exchange the manor of Halnaker in Boxgrove for Wherwell in Hampshire in 1540 and thus had no further link with Boxgrove, …. Added to this was the abolition of chantries in 1547, which meant that by the time of de la Warr’s death this could only have functioned as a tomb.

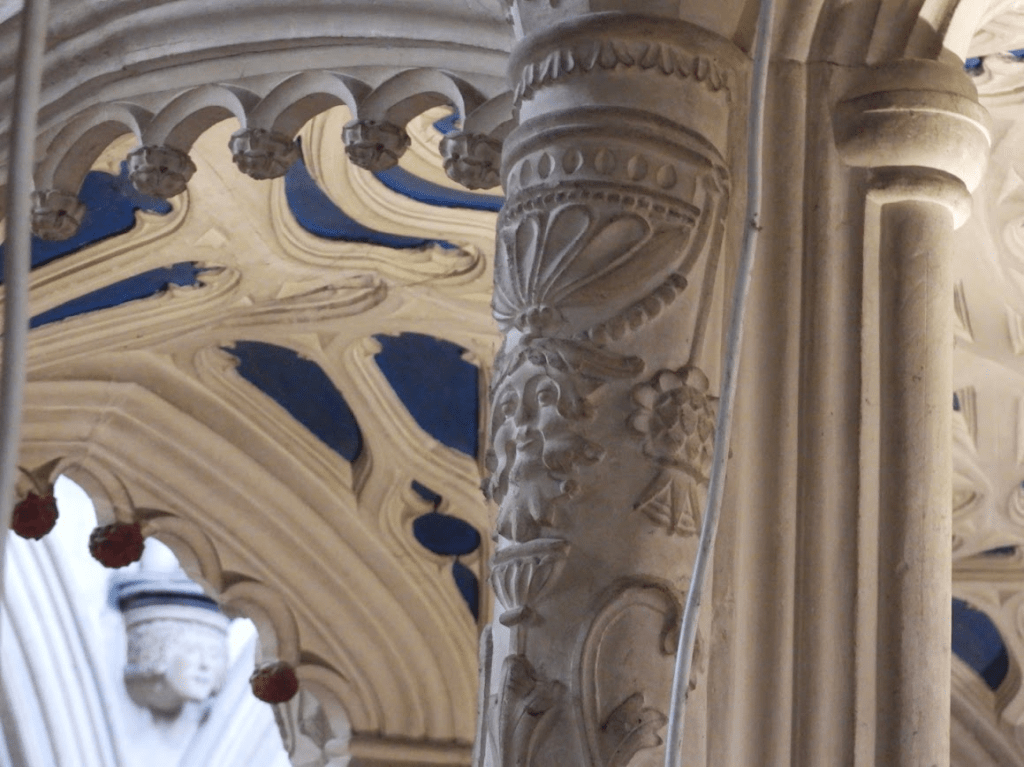

The plan is rectangular with two bays on the long sides, each with pairs of cusped arches separated by pendants, which are also present on the vault inside – the short ends have none. The base is essentially gothic, decorated with shields within lozenges. The upper part, especially the corner-shafts and those between the bays, is covered in Renaissance ornament of shallow incised figures and foliage, some based on Paris woodcuts of c1500 The canopy also combines such decoration with gothic elements – pairs of angels and putti hold shields with straight heraldic decoration. Tiered niches for statues, if ever filled, are now empty. Inside, the reredos has more empty niches, either side of a blank space intended for a carving. Each side of the reredos is an opening, of which that to the main nave of the church served as a squint. The purpose of the recess to the south was probably to provide symmetry. A small opening on the south side but lower down is too small for a piscina and its purpose is uncertain. The painted interior is mostly restored and the iron gates survive. Sussex Parish Churches Boxgrove St Mary and Saint Blaise

Foliage is a key aspect of the iconography of the chantry It is believed that the animals (real and fictious) come from a French Book of Hours (which one not known); but there are other sixteenth century resources that could be a source for the sculptured imagery e.g. Master of Claude de France’s Book of Flower Studies (ca. 1510–1515); some of the studies can be viewed on-line from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection in New York see Book of Flower Studies Master of Claude de France ca. 1510–1515

The flowers above these imaginary beasts look very similar to the marigolds

in Master of Claude studies image from: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/823979

but that does not mean that the anonymous sculpture of the De La Warr used this study as a pattern, as images of all flowers in the 16th century are very stylised; the idea could have come from many manuscripts depicting flowers

The marigold was nicknamed “Mary’s Gold” due to several legends linking it to her. One story claims that when Mary’s purse was stolen on the flight to Egypt, all the thieves found were petals, so early Christians left marigold petals around her statues as a substitute for coins. Jonathan Hoyle, Society of Arts, Medieval Natural Symbols

Heaven is often depicted as a return to the garden of Eden in Medieval and Early Modern manuscripts. So the intent of the artist in including much foliage in the chantry may have been to suggest that heaven was where Thomas, Lord de la Warr would go after death. The Tudor roses on the Chantry show Thomas’s allegiance to Henry VIII; opponents of Henry often had their earthly lives shortened by judicial or extrajudicial execution

The flowers on to the left of this beast may be chicory

they are similar to Master of Claude’s chicory. Pre-reformation church sculpture was typically polychrome, often painted painted in gaudy colours but the colour wears away over the years; the colour of sculptured plants would make it easier to assign to possible specific botanical species

The plant’s ability to thrive along roadsides in difficult, disturbed soil, coupled with its strong, deep taproot, made it a symbol of Christian perseverance and resilience in the Middle Ages. The plant’s steadfast nature, even through cold winters, linked it to the endurance of faith. Riklef Kandeler, Wolfram R. Ullrich, Symbolism of plants: examples from European-Mediterranean culture presented with biology and history of art: NOVEMBER: Chicory, Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 60, Issue 14, October 2009, Pages 3973–3974, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erp248

Here is some Chicory I photographed at Singleton; close by Boxgrove, in 2024. Chickweed was grown for its seed; and it is common in Sussex as a arable weed.

Though C. intybus was formerly regarded as a native, at least in England and Wales, doubt is now cast on that status in most counties, and it is almost always treated as a relic of cultivation. Historically, it was cultivated for its seed (subsp. intybus) British and Irish Botanical Society Plant Atlas 2000 It would have been common in the arable fields around Boxgrove in the C16

There are foliate heads. often called Green Men;, carved in the chantry, although the second of these images looks more like a foliate head of an animal or mythical beast. Lady Raglan only coined the name Green Men in 1939; it has no historical heritage

There is voluminous writing on the Green Man motif representing a pagan mythological figure, as proposed by Lady Raglan in 1939 Raglan, Lady. “The Green Man in Church Architecture.” Folklore, vol. 50, no. 1, 1939, pp. 45–57. doi:10.1080/0015587x.1939.9718148 but her view is not supported be the evidence. Many folklorists believe that foliate heads indicate a perseverance of pagan beliefs after the Christianisation of England. However, as De La Warr had gone to great expense to have the chantry built and have priests pray for his soul (although did not happen because of Henry VIII’s reformation) he would hardly have risked his salvation with what might have been be perceived as pagan imagery. It is far more likely that foliate heads in churches were Christianised symbols of resurrection, as I J B S Corrigan (2019) points out in The Function And Development Of The Foliate Head In English Medieval Churches. Unpublished theses, University of Birmingham accessed 30.11.25 https://files.core.ac.uk/download/pdf/323305511.pdf, which includes consideration of the Boxgrove foliate heads.

This appears to be a thistle

Master of Claud’s thistle

Thistles are associated with the Virgin Mary, It is impossible to say which form of thistle is sculpted on the Chantry but Milk Thistle, Silybum marianum, Also known as the Marian or Mary Thistle, the species name Marianum comes from the Latin and refers to a legend that the milky white streaks on the spiny leaves of this species of thistle came from the milk of the Virgin Mary nursing her child whilst fleeing to Egypt. Bolton Castle Plants

Whether the foliage painting and carvings are attempts at botanical verisimilitude or are entirely symbolic – or something in between – does not bother me – as all you need to do to enjoy the art of Boxgrove Priory Church is visit and look at its art yourself.

A Footnote

Boxgrove Priory Church not only has outstanding Renaissance ceiling painting and Chantry carving, it has some cracking lichens on its external walls, including Ingaderia vandenboomii, which is deemed a “Nationally Scarce” by the British Lichen Society. But it is not that scarce on the north walls of old (mostly Saxo-Norman) coastal churches in Sussex.

Ingaderia vandenboomii has a pink thallus i.e body (the red is a reaction to a chemical reagent spot test used to confirm its identity.