The Weald (the High Weald, Low Weald and Greensand Ridge) was known, by Latin speakers, as Anderida Silva (Wood of Anderida), after Anderida (present-day Pevensey), a Saxon shore fort, as then woodland covered most of Sussex and surrounded Anderida. When the Saxons settled Sussex from the 5th century, the Weald was initially called just Andred (Saxon Chronicles 785 and 893); and then Andredesweald (Andred’s Wood) (Saxon Chronicles 1018). Following the Norman Conquest, the name was shortened just to The Weald (used in the Doomsday Book 1068). Sources: Peter Brandon (2003) The Kent and Sussex Weald, Ch6. The Saxon and Jutish Andredesweald and Marc Morris (2021) The Anglo-Saxons: A History of the Beginnings of England: Ch1 The ruin of Britain

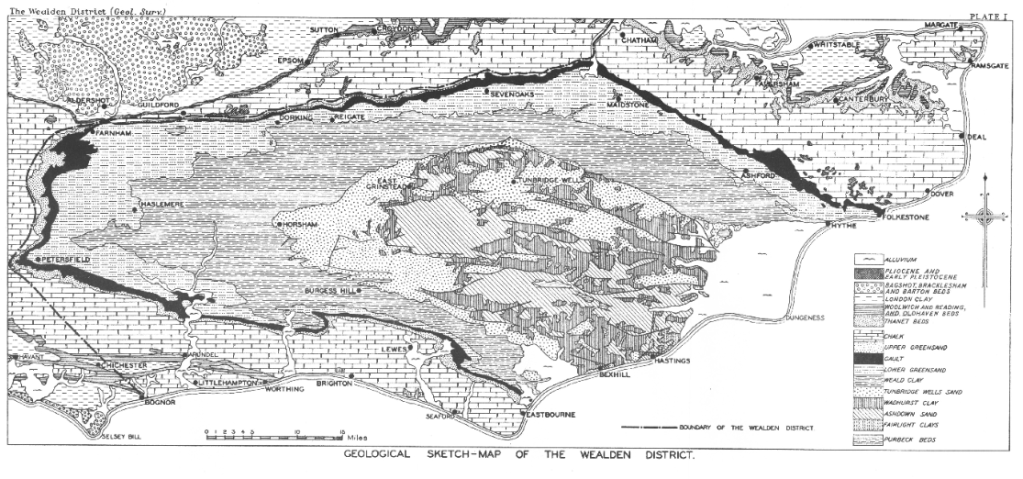

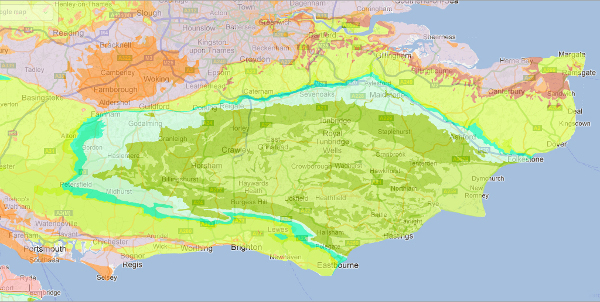

The geomorphology of the Weald is defined by its geology. See R W Gallois (1965) The Wealden district. British regional geology. 4th edition. London: HMSO’ accessible on-line at: https://webapps.bgs.ac.uk/memoirs/docs/B06880.html

The Low Weald is the eroded outer edges of the High Weald, largely coinciding with the outcrop of Weald Clay but with narrow bands of Gault Clay and the Lower and Upper Greensands which outcrop close to the scarp face of the South Downs. Natural England. National Character Area 121: Low Weald

All of the UK’s landscapes are under threat from development in a growth-focussed political climate, but the Low Weald is particularly vulnerable to development as it sandwiched between the High Weald National Landscape (previously called the High Weald Area of Outstanding National Beauty) and the South Downs National Park; both of which have higher levels of protection from development: HM Government: Areas of outstanding natural beauty (AONBs): designation and management. Counter-intuitively the area of low weald between Fittleworth and the Mens, mostly land in the parish of Fittleworth, is within the South Downs National Park. The vast majority of the low weald is not in the South Downs National Park. AONBs [now National Landscapes] … have the same legal protection for their landscapes as national parks, but don’t have their own authorities for planning control and other services like national parks do. Instead they are looked after by partnerships between local communities and local authorities. National Parks UK: National Parks Are Protected Information Sheet However, having planning determined by the South Downs Authority does not necessarily lead to the protection of nature. The SDNPA gave consent to the Towner Gallery’s plan to develop an arts centre on the Black Robin Farm site at Beachy Head, which is likely to harm nature through greatly increased carbon emissions from transport to and from this new venue.

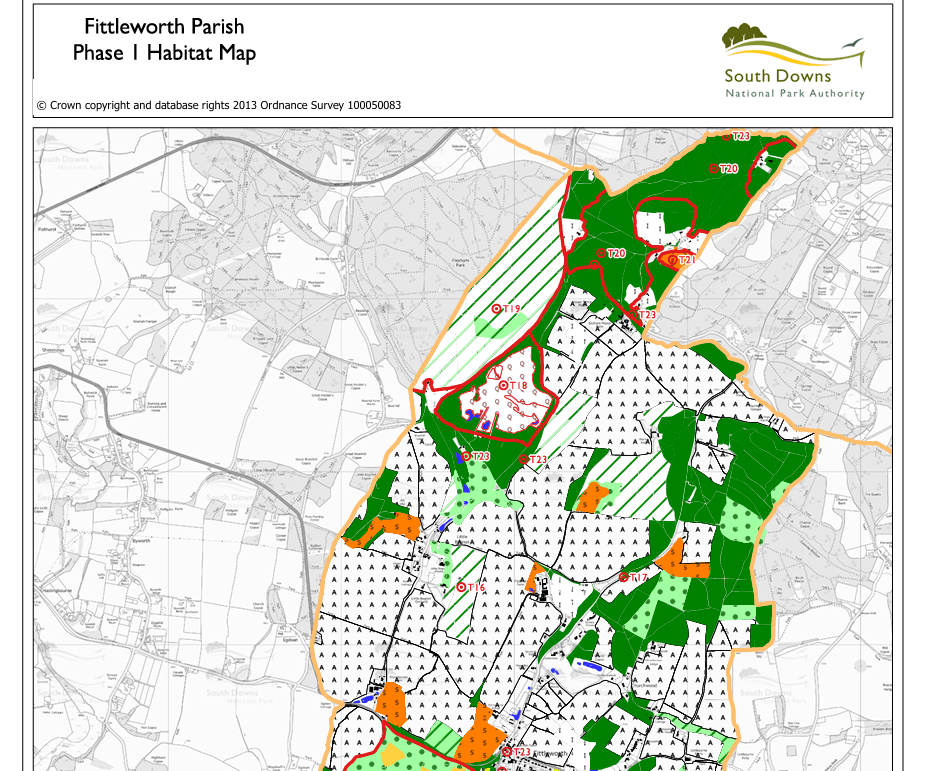

The South Downs National Park Authority records the habitat types of the land in the Parish of Fittleworth, the parish through which my walk passed.

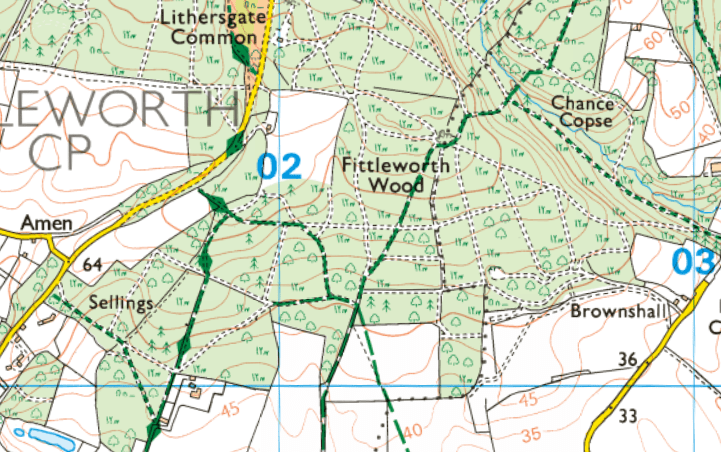

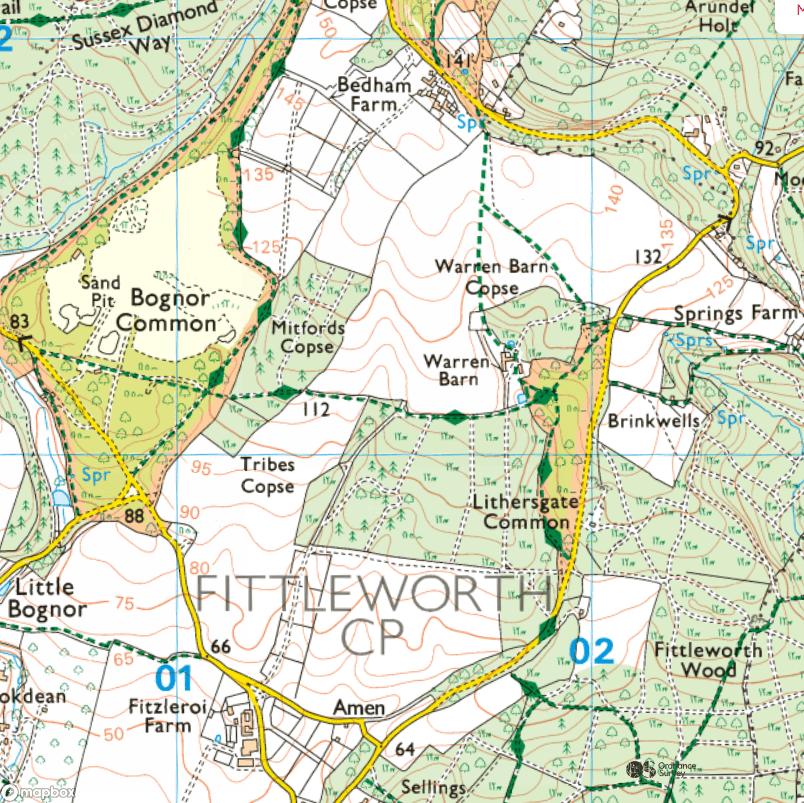

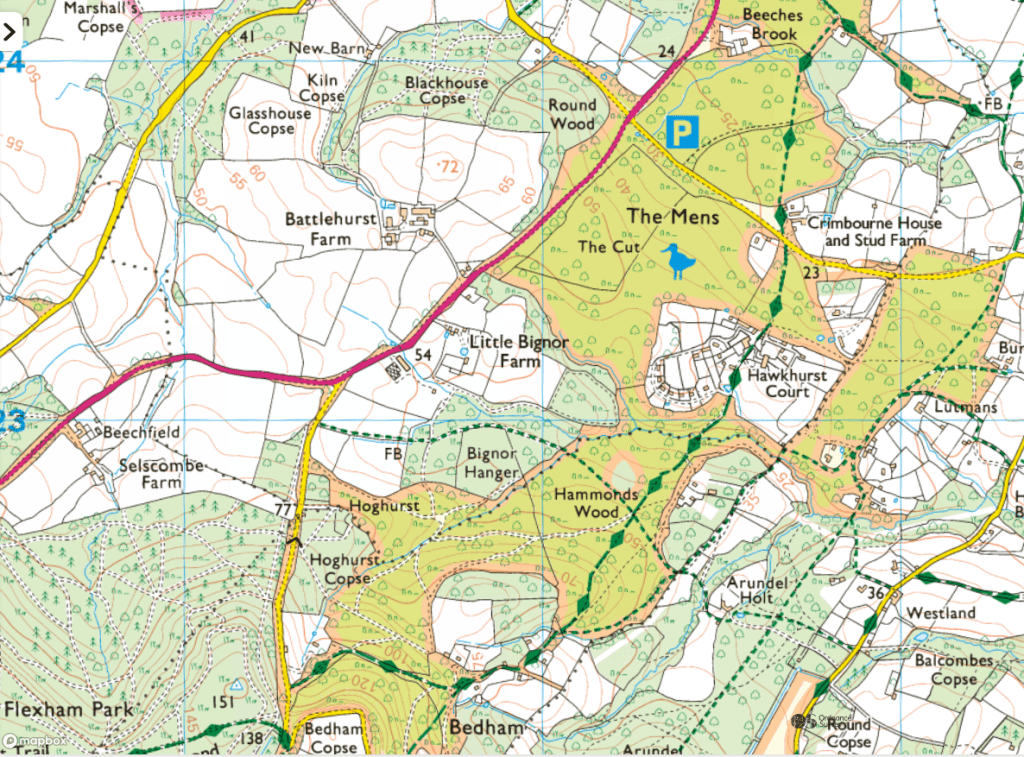

The dark green areas on this map are all, according to the South Downs habitat map, semi-natural broadleaf woodland. This is probably because the Natural England ancient woodland database says they are. But when you walk through them this is clearly not the case. The Mens and Hammonds Wood are Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland (ASNW), which is largely of natural origin; however Fittleworth Wood, owned by the Stopham Estate, is very clearly not, it is Ancient Replanted Woodland, as Natural England designates Felxham Park, which is exactly the same Sweet Chestnut planting as Fittleworth Wood.

When I travel on busses across the Low Weald, which I do frequently, I see large numbers of unaffordable housing developments which have destroyed ancient woodlands and archaic pastures of the Low Weald.

Being drawn toward the past

All cities are geological. You can’t take three steps without

encountering ghosts bearing all the prestige of their legends. We

move within a closed landscape whose landmarks constantly draw

us toward the past. Chtcheglov, ‘Formulary for a New Urbanism’

I would argue that these landmarks exist in the rural landscape too. As long as there is a level of habitation, or the memory of it, we stake a claim to these places. And when the memory is too distant, we interpret. We tell stories of place. Legends attach themselves. … Sites where memory can no longer be directly accessed are such enigmatic places. These stories held in reserve require an interpreter. Someone willing to look at and interrogate place, to unpack and retell the stories. Sonia Overall, 2016 Walking Backwards: psychogeographical approaches to heritage. A paper delivered at Contemporary and Historical Archaeology in Theory (CHAT) Conference: Rurality 2016. University of the Highlands and Islands

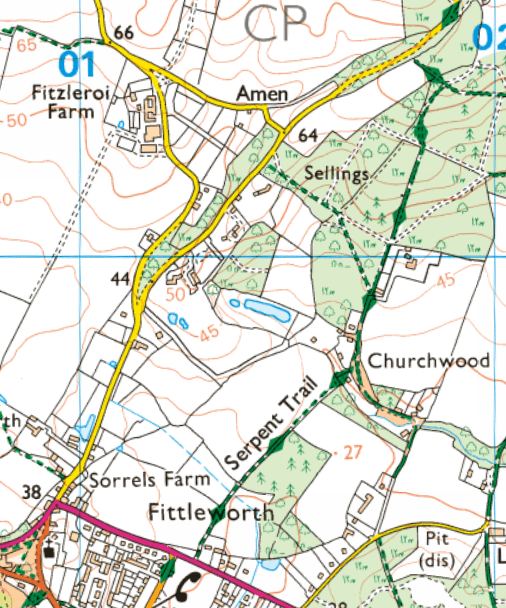

The route of my walk:

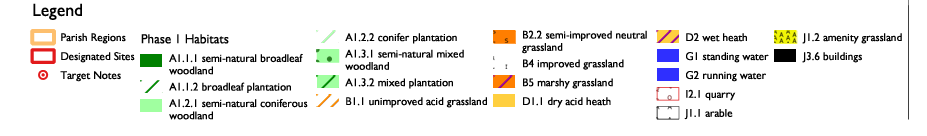

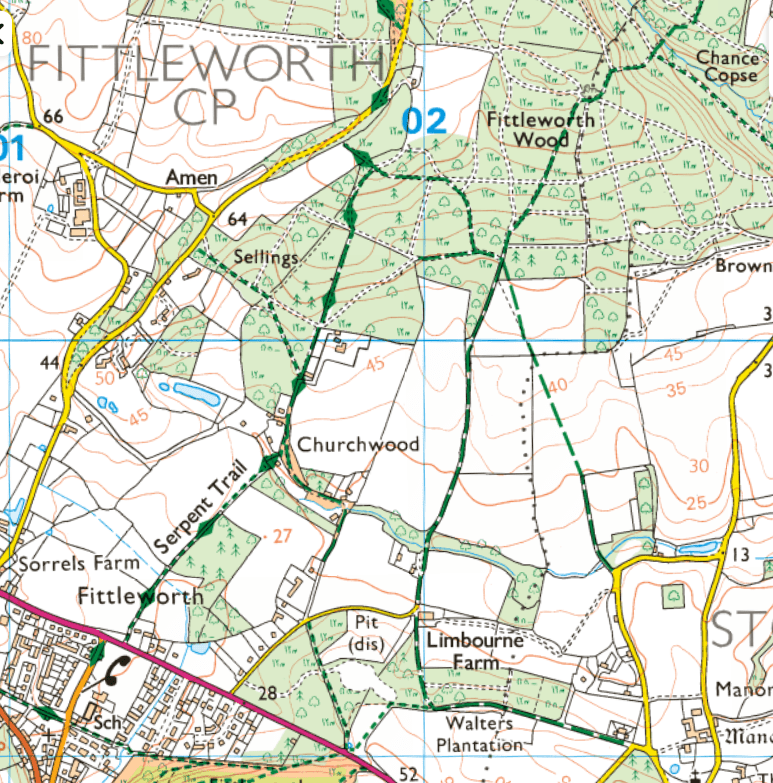

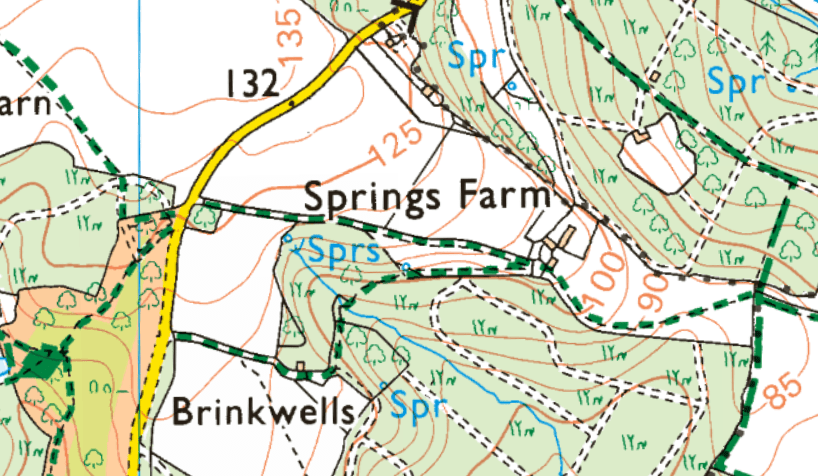

The extracts of Ordnance Surveys in this blog are screen shots from Explore OS Maps on-line

In Fittleworth Wood: my heart sinks; but the past pokes through.

Walking north of Fittleworth along the Serpents Trail, you soon pass through the southwest part of Fittleworth Woods, around Sellings; owned by the Stopham Estate. There is no public access to this land apart from the paths that run through it; over and over again signs tell you that the woods are private

Here, as in many areas of Sussex, ancient oak, beech, hornbeam and other native trees have been felled and replanted with Sweet Chestnut. The main Chestnut area in Great Britain is concentrated in the southern counties of Kent and Sussex, where extensive stands of commercial coppice, amounting to some 18,000 hectares were planted in the mid 19th century. . Everyday Nature Trails: Sweet Chestnut

When I walk through this soulless replanted woodland, I try to imagine its former age-oldness

In this mostly monocultural desert, relicts of the past can still just be seen, and they help me imagine what this landscape was like. Medieval boundary banks, with Oak and Beech growing on them (naturally regenerated from previous planted Beech and Oak, coppiced as was the traditional practice in planted boundary banks) and a few maiden (un-pollarded) Pedunculate Oaks poke through the coppiced Sweet Chestnut monoculture.

Coppiced Sweet Chestnut monoculture:

Ancient boundary bank:

Maiden Oak amongst the Sweet Chestnuts

Lithersgate Commons

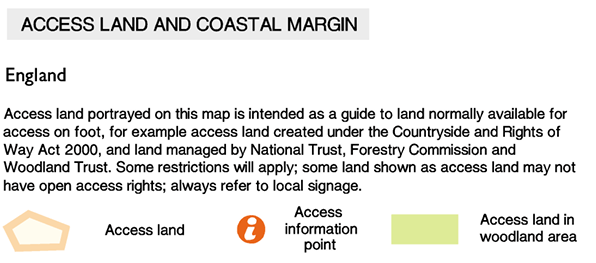

Walking north from Sellings/Fittleworth Wood, I walked through Lithersgate Common. There are no signs that tell you that you are walking through a common and can thus leave the path and wander; you can only know that by looking at the OS map and seeing its name and seeing it is marked as Access Land. Access Land in Woodland Areas is often land that still has common rights. But it is very hard for the general public to know what those rights are.

OS Map Key

All land in England and Wales, including common land, is privately owned. Indeed, larger areas of common land may have many different owners. It’s a widely-held misconception that citizens at large or “commoners” own common land. Instead, what makes the land “common” is the common rights attaching to it, not its ownership. Most common land is now “open access land” giving public right of access to it.

In many cases, rights of common do not just include access. The rights attaching to common land vary depending on the rights granted to the commoners in that particular place. These rights typically reflect the historical needs of the rural poor. They may include rights of:

- Pasture for animals;

- Pannage – the right to allow pigs to feed off acorns and beechnuts;

- Stray – grazing rights for cattle;

- Piscary –the right to fish;

- Estovers – the right to take wood;

- Turbary – the right to cut peat or turf for fuel;

- Soil – the right to remove minerals or soil;

- Animals – the right to take wild animals. BLB Solicitors: What is Common land and What are Rights of Common

First enshrined in law in the Magna Carta in 1215, Common Land traditionally sustained the poorest people in rural communities who owned no land of their own, providing them with a source of wood, bracken for bedding and pasture for livestock. Over one-third of England’s moorland is common land.

At one time nearly half of the land in Britain was Common Land, but from the C16th onwards the gentry excluded Commoners from land which could be ‘improved’ through agriculture. That is why most Common Land is now found in areas with low agricultural potential, but areas which we know hold value for high conservation significance and natural beauty.

Common Land now accounts for 3% of England, but this includes large tracts of our most well-loved and ecologically rich landscapes. Foundation for Common Land: A guide to Common Land and Commoning

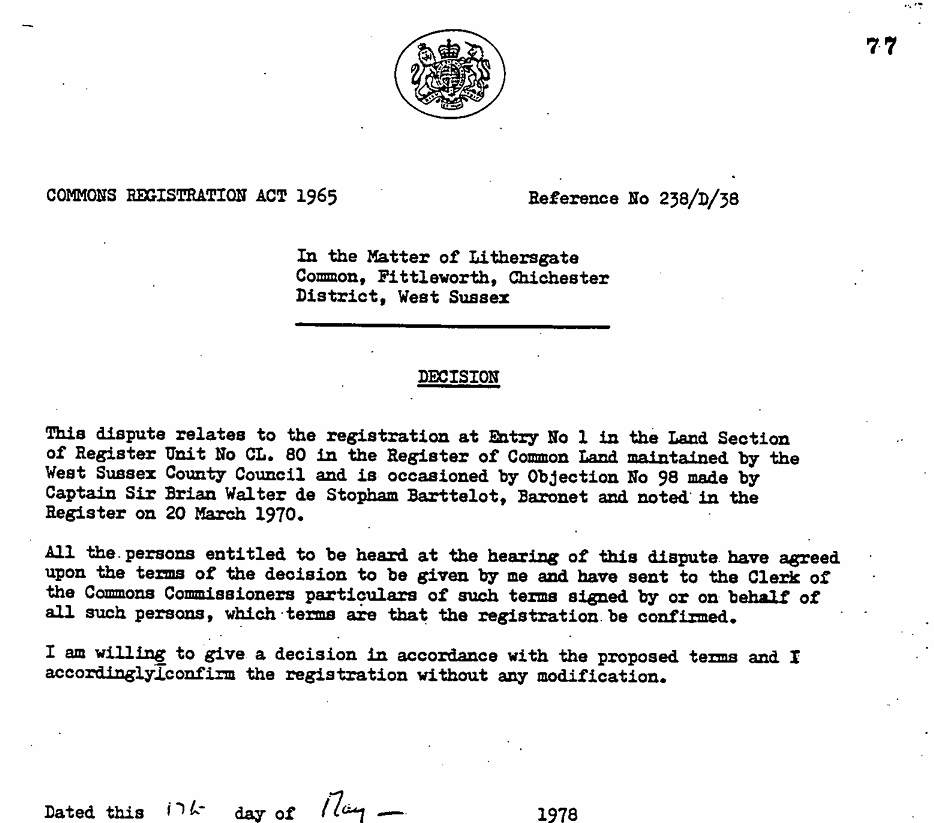

To find out what Rights of Common a common has, you need to make an appointment to see the Register of Common Land held by the Local Authority in which the land is located; for Lithergate Common that is West Sussex County Council. If I owned a few pigs and I wanted to take them to Lithersgate Common so they could munch acorn and beech mast in Autumn I would need to check the West Sussex Commons Register to see if I could do that!

Before the enclosure of lands (which started in the medieval period but greatly accelerated in the 17th and 18th centuries), there was much common land, and ordinary people knew their rights of local commons. Now there is little common land, and few people know where commons are and even fewer know what rights are attached to that common land and who can use those rights.

But even the tiny bit of land with common rights left is constantly threatened by modern-day enclosures. An online search revealed that the status of Lithersgate Common as a common was disputed in 1978 by Captain Sir Brian Walter de Stopham Barttelot, Baronet. The fact that Lithersgate Commons is still marked on the OS map as Common Access Land implies that Captain Sir Brian Walter de Stopham Barttelot’s dispute was not upheld.

The lands of the Bartelots of Stopham are a paradigmatic example of the continuity of aristocratic ownership from the Norman Conquest to the present day of much of the Sussex landscape.

… the Barttelots of Stopham have been ‘remarkably stationary both in place and condition’. It is more than likely that they descend from the Norman, Ralph, who held the manor at the time of the ‘Domesday’ survey in 1086. Stopham was one of numerous manors in Shropshire and Sussex granted by William the Conqueror to his close associate, Roger Montgomery. Roger had been keeping the peace at home at the time of the Conquest, but had been rewarded for his patience with the earldoms of Arundel and Shrewsbury. He in turn had distributed various manors among his own followers. Stopham was allotted to one Robert, who sub-let it to Ralph. Barttelot of Stopham and Westgate of Berwick, Men of Agincourt – A Quest for the Oldest Families in Sussex

The Stopham estate has degraded much of the ancient woodland it owns by replanting ancient woodland with Sweet Chestnut and vines; and they prevent public access to most of their estate, to promote game shooting of pheasant. Vineyards are monocultures reducing biodiversity, and use agrichemicals, as the South Downs National Park acknowledges Viticulture Growth Impact Assessment Aside from the immorality of shooting, the government classify pheasants as a species that cause ecological, environmental or socio-economic harm. Pheasants and partridges gobble up native vegetation, insects and reptiles, and they leave their droppings all over sensitive habitats. When they are dead, they are feeding foxes and scavengers, which then eat other protected species. Mark Avery, co-founder of Wild Justice quoted in Patrick Barkham (2020) The Guardian. Pheasant and partridge classified as species that imperil UK wildlife

What is the purpose of pheasant shooting and viticulture? Shooting days and English wine are expensive products that are only affordable to those on a high income; and the deliver profit to businesses owned by the landed gentry.

One might ask:

- is it just for large areas of Sussex to be owned by the landed gentry simply because they have inherited it; especially when that land was originally taken from its previous owners/users a 1000 years ago

- if you own ancient woodland should you be allowed to degrade it by replanting it for profit

- if you own ancient woodland should you deny public access to it

As the South National Park Fittleworth Parish Habitat Survey, 2015, acknowledges, north of Fittleworth is very influenced by the estates which surround it; Barlavington, Stopham and Leconfield in the immediate vicinity, and beyond Cowdray, Goodwood and Arundel. All of these estates bar public access to much of their land, often because they run pheasant shoots.

In the words of Gerard Winstanley (1609 – 1676) leader of the “True Levellers” (Diggers): the Gentrye are all round; on each side they are found, there wisedomes so profound, to cheat us of our ground

Around Brinkwells: melancholia and folklore

From Lithersgate Common I walked to Brinkwells and explored the land around it. Brinkwells lies to the north of Fittleworth, to the East of Bedham

This is the route to Brinkwells ,suggested by Elgar to a violinist friend, in a hand-drawn map of 1921. Map reproduced from Fittleworth Miscellanea. Map is in the collection of the Royal College of Music.

Brinkwells: Cottage. C17 or earlier timber-framed, refaced with stone rubble. Hipped thatched roof. Casement windows. Two storeys. … Sir Edward Elgar lived in this house from 1917-1919. He composed his cello concerto while living in the house. Historic England listing: Brinkwells He also composed there the Piano Quintet in A Minor, Op. 84 in 1919, the same year as he started the cello concerto.

[T]here’s a deeper side to Elgar’s music- a sense of introspection, loneliness, and even melancholy. This is what we hear most strikingly in the Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85. It was Elgar’s last significant work, written during the summer of 1919 at “Brinkwells,” his cottage near the village of Fittleworth, Sussex. The summer before, he had been able to hear the sound of distant artillery in the night, rumbling across the English Channel from France. The Listeners Club: Elgar’s Cello Concerto: Elegy for a Vanishing World.

I know Elgar’s cello concert well; Jacqueline du Pre’s recording was played by my parents in my childhood house often. The introspective and elegiac nature of the concerto is profound. Landscape landscape nature, contrasting with the grand, confident style of his earlier works.Elgar withdrew from London for the quiet of the Sussex countryside, where the natural landscape restored some of his peace of mind. There, in the summer of 1919, he produced a late flowering of chamber works along with the Cello Concerto, all marked by a new simplicity and restraint. Nashville Symphony Cello Concerto in E minor, Op. 85 Nature and landscape inspired Elgar’s music. Is the relationships between landscape and music bidirectional? Could our emotional experience of a location be influenced by our experience of music inspired by that location.

Just to the north of Brinkwells, the replanting of the ancient woodland with Sweet Chestnut was inhibited by an area of undulating land, produced by a series of streams emanating from natural springs, making replanting difficult, so veteran beeches and oaks are the dominant trees. Spring Farm just to the north of the springs takes its name from them but none of the land around the springs is farmed.

The landscape of this area of springs

Elgar’s wife Alice suggested in her diary that the Quintet was inspired by a local legend about impious Spanish monks who, having engaged in blasphemous rites, had been struck by lightning and turned into a grove of withered trees near the cottage. Alice speculated that the Quintet’s “wonderfully weird beginning” represented those sad and sinister trees. Elgar himself described the first movement as “ghostly stuff.” It begins with an eerie introduction: an austere piano motif that is interrupted repeatedly by muttering strings, followed by a sighing motif and a plaintive rising phrase from the cello. Barbara Leish Piano Quintet in A Minor, Op. 84 (1919): Program Notes Sebago-Long Lake Music Festival

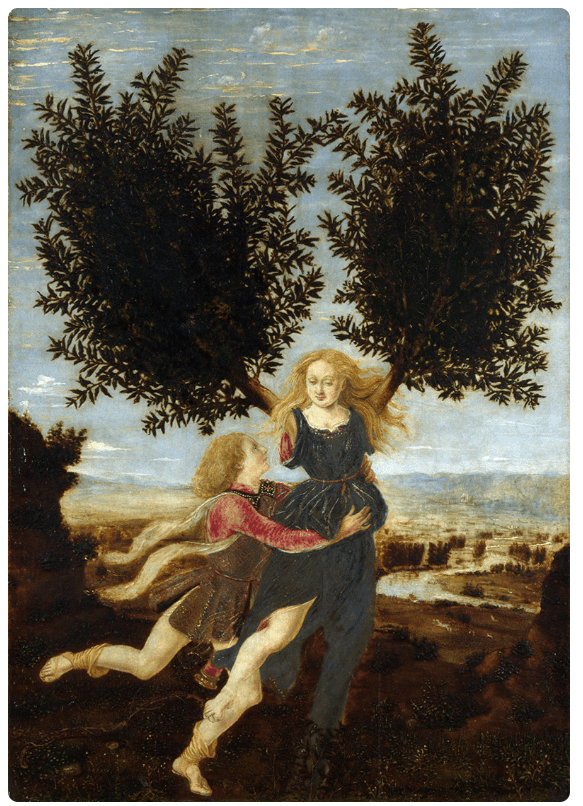

Human-tree transformations, as a result of human transgressions, are common in mythology, for example in Ancient Greece it was believed that the beautiful nymph Daphne who rejected the love of Apollo and is turned into a tree as a punishment. There are no Ancient Greek written sources for this myth, just later Hellenistic ones e.g. Parthenius, 1st century BCE and the more well-known Roman poet Ovid’s version in his Metamorphoses 8th century CE.

I can find no sources for a folklore tradition around Brinkwells concerning Spanish monks turned into trees. It is possible that Elgar’s wife created the story of impious Spanish Monks, in the context of long standing folklore traditions that trees were more than just biological components of the landscape. [I]n Anglo-Saxon culture, trees were more than just elements of the landscape. They were powerful symbols and played an active role in myth and ritual. Legends in the Leaves: Unveiling the Mystical Folklore of UK Trees

Extensive tree folklore, makes it is hard to approach trees in wooded landscapes, without the multiple uses of trees in folklore colouring our perception. On walks, we can be creative. When I see a particularly interesting tree sometimes I make up a story about it; those stories are always influenced by my knowledge of tree folklore; but you can always add a creative twist of your own, as probably Mrs Elgar and possibly Ovid did. As Sonia Overall, 2016, says: Sites where memory can no longer be directly accessed are such enigmatic places. These stories held in reserve require an interpreter. Someone willing to look at and interrogate place, to unpack and retell the stories.

Geology and landscape types of the weald

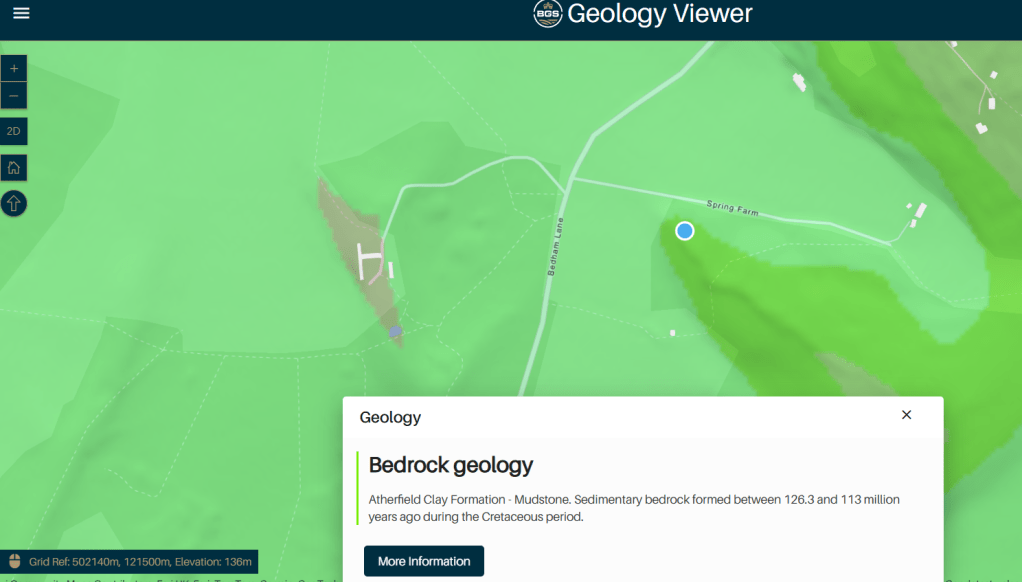

The perseverance of the small area of old woodland north of Brinkwells, that may have inspired Mrs Elgar to retell or create a legend, through the non-replanting with Sweet Chestnut there, is a function of the presence of the springs of that area, and their impact of the springs on the area’s geomorphology. Springs result from the particular geology of their location. An understanding of geology is essential to understanding the landforms of the weald.

Unusually diverse rocks and soils … underlie the exceptionally varied Sussex landscape. … Such are the rapid alterations in the geological canvas that even a short journey introduces the traveller to a number of individual scenes each with a different human imprint. These extend even to the finer details of domestic architecture or hedgerow patterns so that the study of the evolving Sussex landscape is like tracing every thread of a complicated tapestry. As S. W. Wooldridge lucidly demonstrated in The Weald, the geological map is “par excellence our guide and key” to the differing historical development of the traditional Sussex landscape. Peter Brandon (1974) The Sussex Landscape p. 19

Springs formed here north of Brinkwells where permeable sandstone (here sandstones of the Hythe Formation) meets impermeable clays (here the Atherfield Clay Formation); and they are common in the low and high weald.

If you want to know what the underling geology of where you are in Sussex, the days of getting out a paper geological map, as I did when I studied geology in 6th form (1978-80), have gone, and have been superseded by online maps that can be accessed from a smart phone anywhere you are: as long has you have reception: British Geological Survey: Geology Viewer

From Springs Farm to Bedham: Walking along a sunken trackway through the Greensand Ridge. in the footsteps, hoofsteps and trottersteps of medieval farmers and their livestock.

This part of a ‘C’ road that links Springs Farm with Bedham is a now metalled, but it is sunken trackway of medieval origin, with coppiced and pollarded beeches along its banks. Its physical depth may evoked a sense of deep time. A growing body of research suggests there are myriad psychological benefits to feeling small in the face of nature’s vastness: it dampens the ego, and can foster feelings of humility, reciprocity and generosity. Most of these studies have focused on the physical world – boundless landscapes or the enormity of the cosmos, for instance – but one recent paper, by Matthew Hornsey and colleagues, showed there are also upsides to experiencing smallness in time. Richard Fisher (2025) The benefits of thinking about deep time in psyhce online; accessed 10.10.25

Wealden Greensand landscape … is essentially a medieval landscape with a small scale, intimate and mysterious character which is in striking contrast to the openness of the rolling chalk hills of the neighbouring South Downs. Its varied and complex landscape is comprised of a combination of clays, sand and sandstones which have produced an undulating topography of scarp and dip slopes, well wooded with ancient mixed woodland of oak, ash, hazel, field maple and birch. … Many narrow winding lanes are distinctively deeply sunken lined with trees whose exposed twisting roots grip chunks of sandstone. These lanes evolved before road surfacing and were eroded through the ages by weathering and the passage of foot, hoof and trotter as farmers drove their pigs up to the High Weald’s woodlands to feed them on

the abundance of acorns (examples of transhumance and the practice of pannage). THE WEST SUSSEX LANDSCAPE Character Guidelines Local Distinctiveness

Wealden Greensand Character Area

The light and dark areas of this geological map show the greensand ridge; which produces the high ground on which Bedham sits

Bedham School: A picturesque ruin an a reminder of rural poverty and depopulation

Walking along the ancient route from Brinkwells to Bedham Manor Farm, on the summit of the Greensand Ridge, you reach the start of a footpath heading northward through Hammonds Wood. Just a little way down that footpath, on the left is the ruin of Bedham Church

Built in 1880 as a church and school, this Bedham Church was built as a place of worship and education for the remote hamlet of Bedham. At its peak it had 60 pupils and 3 teachers. Derelict Places: Bedham Church

Standing just over two miles to the east of the small town of Petworth, in West Sussex, is an English hamlet on lands that hide a haunting ruin of a building and the story of how it came to be vacant, and almost vanished. The name of this hamlet is Bedham, and on its lands there once stood a farm, a number of houses scattered among the trees, and a school, Victorian by design. … In the midst of this green woodlands, there barely stands a church. Its history began in 1880 with a man named William Townley Mitford. A Victorian Conservative Party politician by vocation, William is tagged as the man behind this Victorian church that is erected in honor of Saint Michael and All Angels. But besides serving as a church, this structure was also used as a school. … During Sundays, the school became a church. All of the school materials were removed, and the chairs were turned so that they faced east. Then came the rector of the small village of Fittleworth to hold the service. He was always accompanied by a lady who played the melodeon. The rest of the weekdays, the building took its regular role of a schoolhouse.

Back in the days, there were around 60 pupils–the younger pupils were children to the local charcoal burners–and no more than three teachers to take care of them. The interesting thing about this school is that it educated both children and adults. A mere curtain separated the groups. …This enchanted forests surround Bedham school and church. But over the years, the need for a school as well as a chapel slowly faded until it was no more. The end, according to some researchers, came around 1925. Brad Smithfield Vintage News: Bedham School and Church: A ghostly shell of Victorian days

Ruins and trees is a common motif in picturesque painting and literature of the 18th and 19th century. See Anna Elizabeth Burton (2017) Ruins and Old Trees: Silvicultural Landscapes and William Gilpin’s ‘Picturesque’ in the Long Nineteenth-Century Novel Picturesque is an idea introduced into English cultural debate in 1782 by William Gilpin in Observations on the River Wye, and Several Parts of South Wales, etc. Relative Chiefly to Picturesque Beauty; made in the Summer of the Year 1770; travellers were urged to the face of a country by the rules of picturesque beauty.

The idea of the picturesque informs the way we see landscape. It is clear from the many internet blogs and articles on visits to Bedham church/school that it is a perceived as a picturesque landscape: Spooky but charming Sussex Live Reclaimed by nature, the ruins of Bedham Church and School are as beautiful as they are eerie. Experience Sussex

Seeing the ruined church school in stunning woods at Bedham is a picturesque visual pleasure; even if an eerie pleasure. It’s the sort of place that you might expect to find Sir Gerwain’s Green Knight, although the Green’s Knight’s Green Chapel was a barrow. (There are many Bronze Age burial barrows in Sussex, but they are found on the Downs not low weald; perhaps the most famous is Cissbury Ring)

In addition to a picturesque lens, Bedham Church could be seen through sociological lens. Rural depopulation in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, and rural poverty, was mostly a result of the end of the capital utility of previous forms of country employment. The psychogeography exposed by Sonia Overall in Walking Backwards: psychogeographical approaches to heritage, is based upon the political philosophy of Situationist International. Activities like walking the city aimlessly were reimagined as statements against a society that demanded production, The Art Story: Situationist International. You could see at the ruins of Bedham as a symbol of the savagery of the capitalist focus of production in causing poverty. The children left when their parents had no work and had to relocate because the capitalism had no need for the production of charcoal any more

West Sussex was a classic zone on the receiving end of the increasing economic divisions … Turmoil in rural Sussex had been rife at the turn of the century, marked by harvest failures, disorder and protest about food monopolies and inflated prices. Eric Richards ‘West Sussex and the rural south’, The genesis of international mass migration: The British case, 1750-1900 (Manchester, 2018; online edition, Manchester Scholarship Online, 19 Sept. 2019), https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9781526131485.003.0004, accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

Hammonds Wood (a cathedral of beech)

To reach the Mens from Bedham you walk through Hammonds Woods. This wood is mostly tall forest woodland of Beech and some Pedunculate Oak, with an understory of Hawthorn, Field Maple, Yew and a great deal of Holly. Hammonds Wood is part of the Natural England The Mens SSSI and is managed as part of the Sussex Wildlife Trust The Mens Nature Reserve. The Mens is a Nature Conservation Review site, Grade I and a Special Area of Conservation. An area of 166 hectares (410 acres).

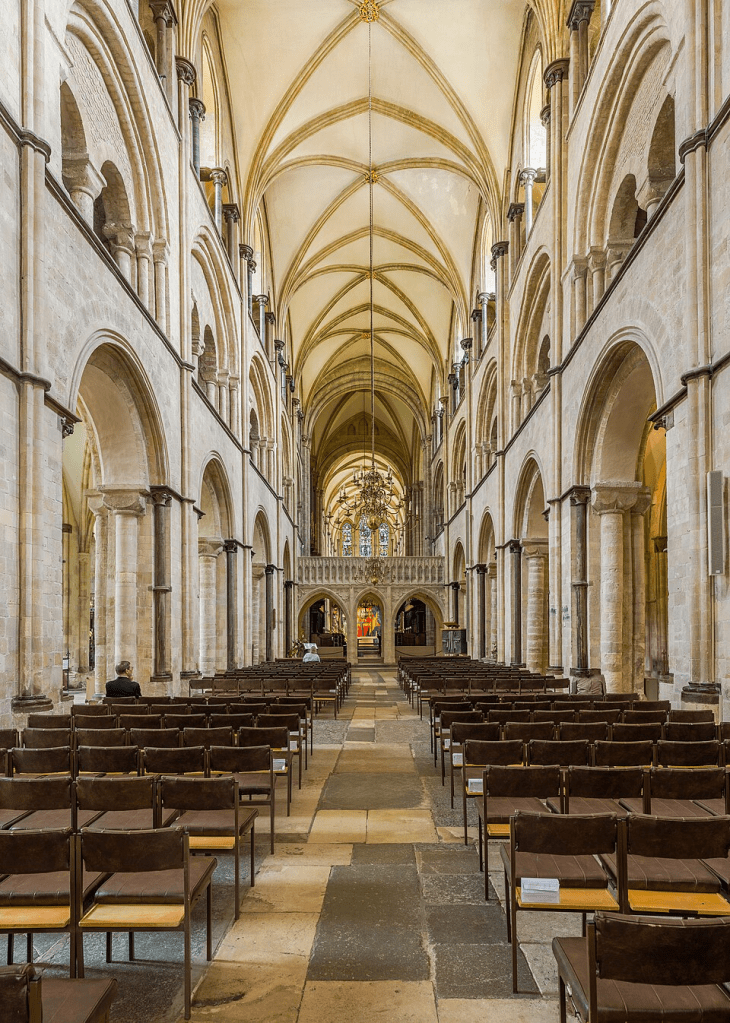

A cathedral of trees is a oft-used metaphor to describe awe, reverence, and the natural beautify of woods. It also suggests that nature itself can be a sacred space. Walking through Hammond Wood did fill me with are of its natural beauty but it also felt physically like had a feel of walking along the nave and aisle of a Romanesque (Norman) cathedral.

like Chichester’s Romanesque/ Perpendicular nave

Diliff, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Mens (pasture woodland)

Arriving in the Mens is always a pleasure, as there I feel there a deep connection to the medieval past, even though its present form is very different from its medieval past. Its name reveals its Saxon origins. The unusual name of this area comes from the Anglo-Saxon word ‘gemænnes’, meaning common land. Sussex Wildlife Trust The Mens

The Mens was previously wood pasture; probably mostly an area pannage in the medieval period. It was transformed to tall forest woodland from wood pasture when grazing ceased. The Sussex Wildlife Trust has not reintroduced grazing at the Mens. Historically, pannage is the legal right to pasture swine in woodland, a practice which was prevalent in mediaeval England. The right of common of mast, otherwise known as pannage, has been going on for a thousand years [and continues in the New Forest]. Curiously British: Pannage

As you start to wander through the reserve, you will begin to orientate yourself – there are old tracks and banks separating woodland compartments and heavily incised streams full of bryophytes that fracture and divide the site. Whilst there is much beech, as at Hammonds Wood, in the Mens there is much Pedunculate Oak too; Oaks of many different shapes and sizes form a more intimate atmosphere with typical ancient woodland trees such as Wild Service, Midland Hawthorn and Spindle. Sussex Wildlife Trust The Mens

Wild Service Tree in the Mens

Midland Hawthorn in the Mens

Hawthorn, Crataegus monogyna has single seed in its fruit (monogyna), while Midland Hawthorn,Crataegus laevigata, has two or more seeds in its fruit

We have always maintained a policy of non-intervention in the main woodlands and continue to monitor changes in tree growth and development, species diversity, succession and the extent of deadwood. Sussex Wildlife Trust The Mens Reserve This policy of non-intervention in the Mens makes sense in terms of leaving dead wood as a habitat to invertebrates and fungi, but it means that the Mens now will never again look like the Saxon gemænnes, as the landscape of Saxon Commons was a landscape formed by human intervention, mostly pannage; Whilst it is still ancient woodland, it is nothing like the pasture woodland that it was in medieval times. But glimpses of the past can be seen in the old tracks and banks. Most current ancient woodlands are little like their past former forms; but these woodlands are still important to conserve; with grazing, coppicing and pollarding. Ancient woodlands are not natural or wild in Sussex, nor are the anywhere; but they are very beautiful and of great ecological importance.

The wildwood, as discussed by Rackman (e.g the 1976. Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape), the natural forested landscape that developed across much of Prehistoric Britain after the last ice age, has gone (and probably never covered all of what is now the England as Rackham originally argued); from the start of the Neolithic period, people began to shape the land.

Whilst ancient woodland is important and needs preserving; we also need to think of the future of the landscape and consider how to preserve and promote nature recovery in a landscape that also needs to produce food in a sustainable way; food production that is democratic, collaborative and not driven by profit. The landscape of Sussex has not always been, and should not always be in the future, predominantly a landscape of woodland primarily used for cash cropping, business farming driven by profit and a middle class and aristocratic leisure landscape (hunting, private walking, playing golf). It could be a sustainable landscape of nature and regenerative community farming providing sustainable food and well-paid employment.

On the way back to Fittleworth; the sound of a pig

On the way back to Fittleworth from the Mens I walked dowm the lane to the west of the Serpents Trail

I heard a snuffling sound whilst walking down the lane, and looked over a hedge and saw a pig thoroughly enjoying acorns that had fallen from a pedunculate oak in a field. The pig was not in common pasture woodland; it was in a field; it was not a native species, it was probably a Vietnamese Pot-Bellied Pig; it was not livestock, it was probably a pet; but the sight and sound of a pig enjoying acorns from an Oak in the countryside paradoxically strangely drew me more toward the medieval past of the landscape than any other experience of the day.