Music composed by David Fanshawe for David Gladwell’s film 1975 Requiem for a Village.

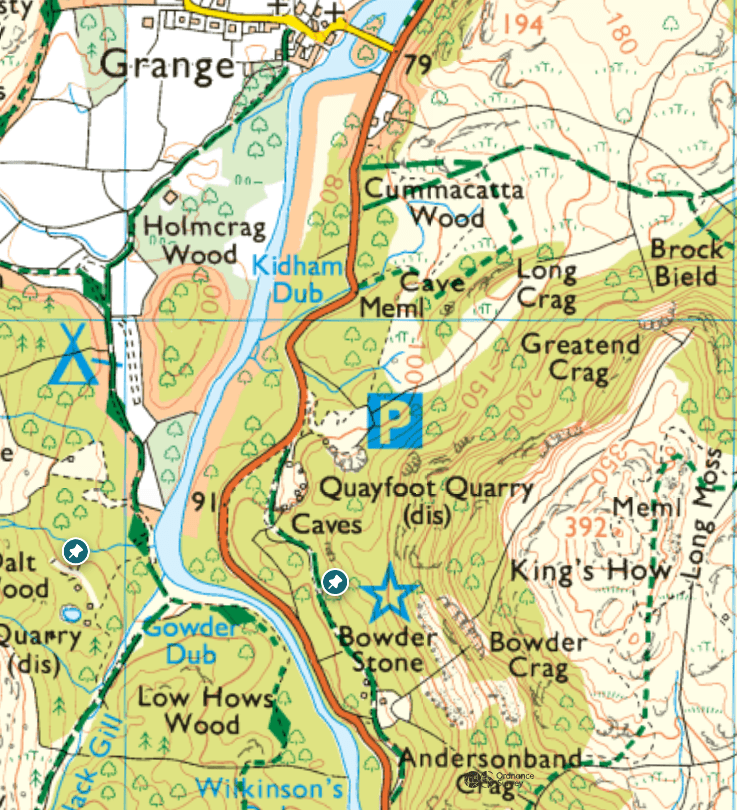

Tree felling (out of sight) at the Oakhurst (Countryside Homes, The Hill Group) building site, Freek’s Lane.

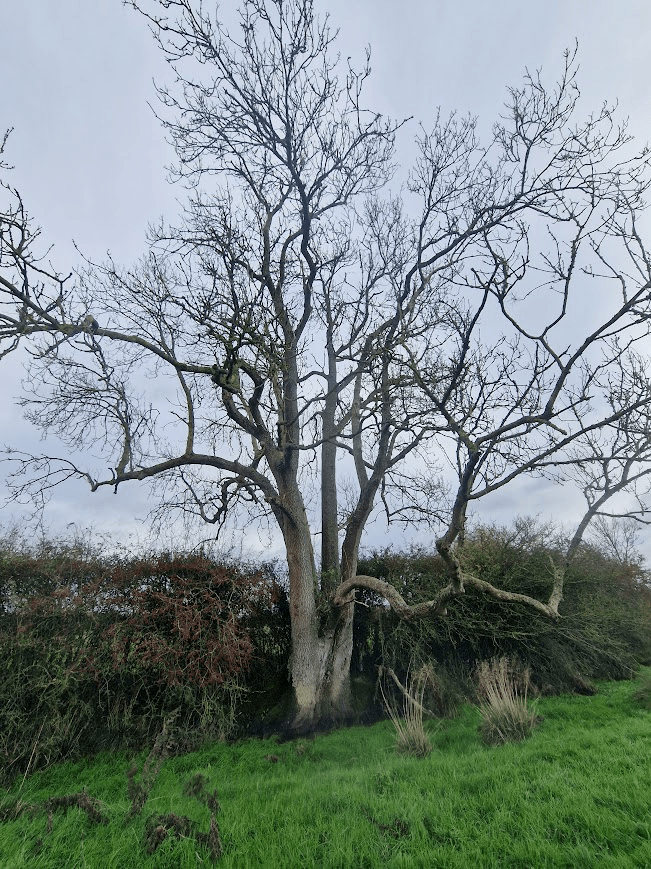

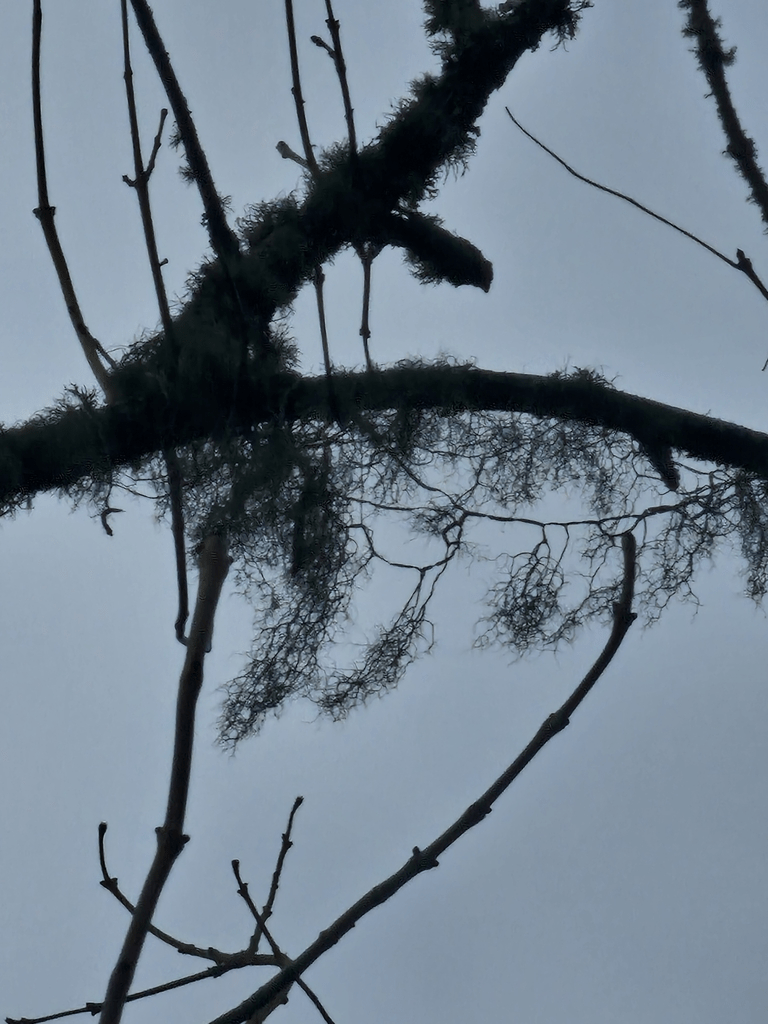

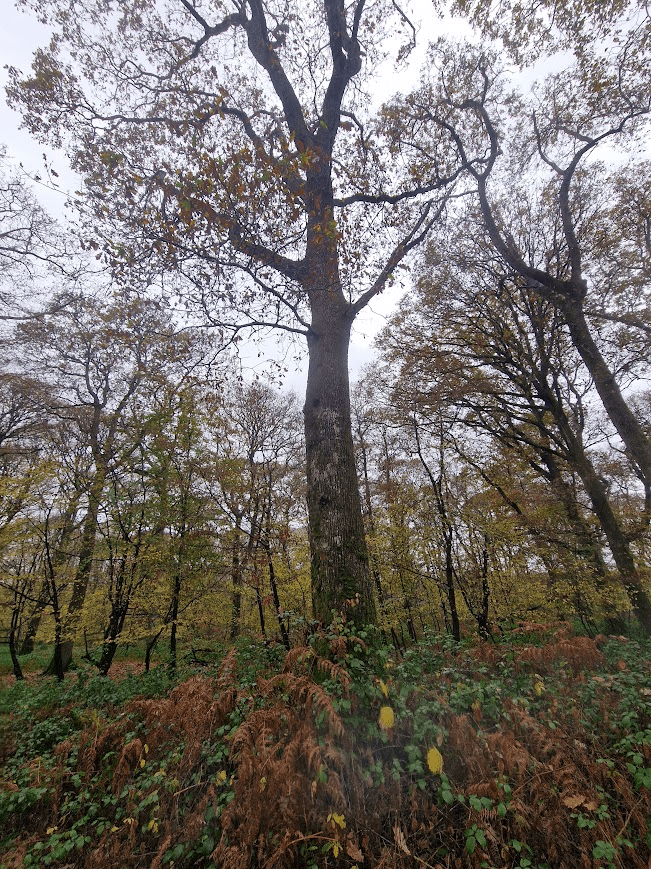

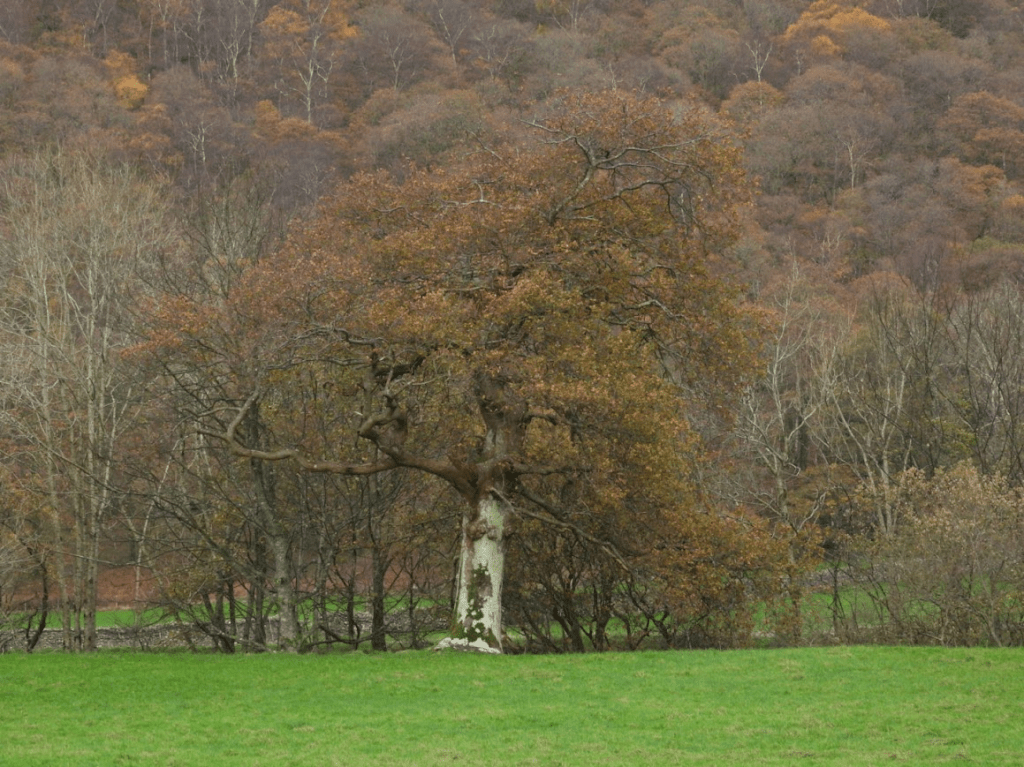

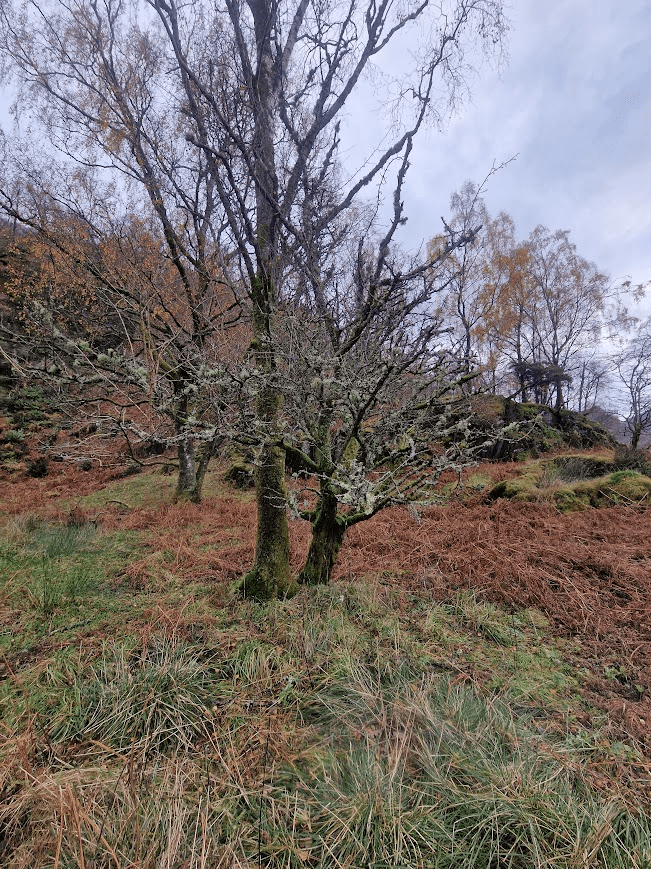

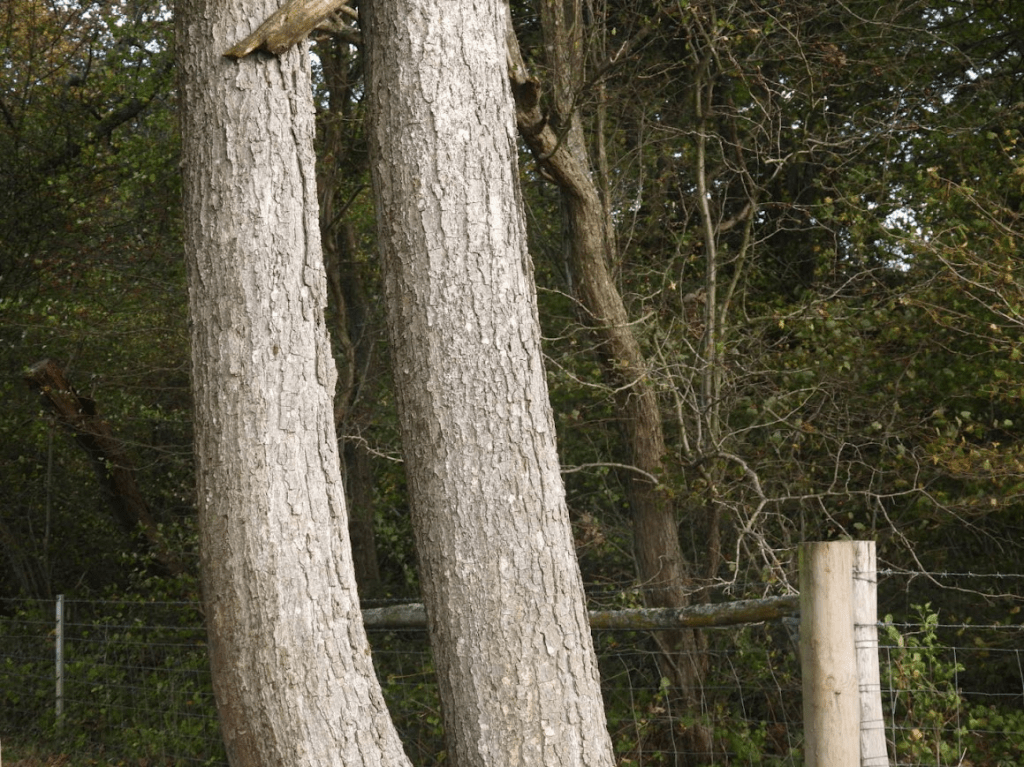

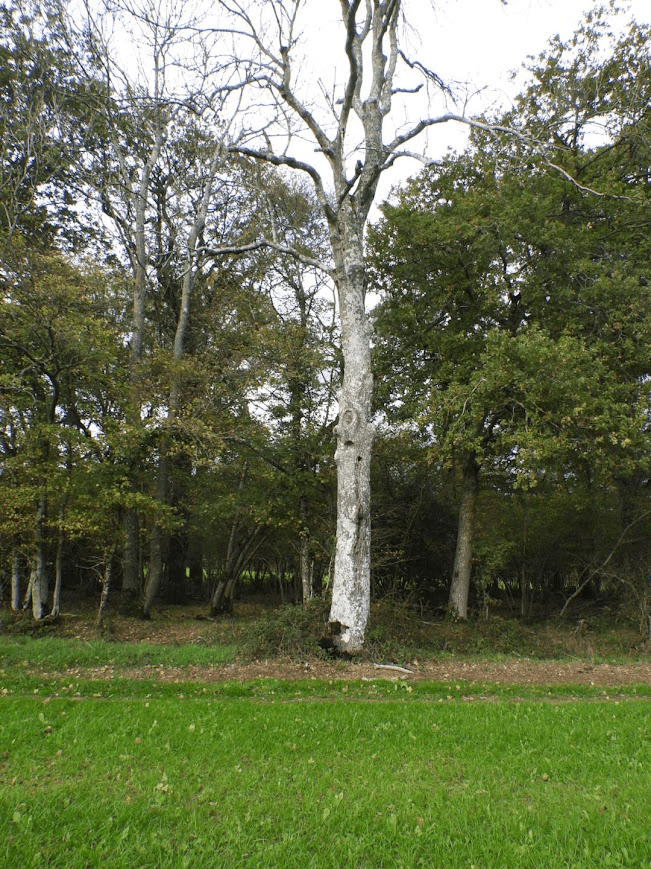

A Pedunculate Oak that has thus far survived the felling; right outside the information kiosk/show home. I don’t think it will be felled, as it helps Countryside Homes (The Hill Group) to delude people that they are not buying a house on a new estate that has destroyed Low Weald countryside; but they are buying a house in the countryside.

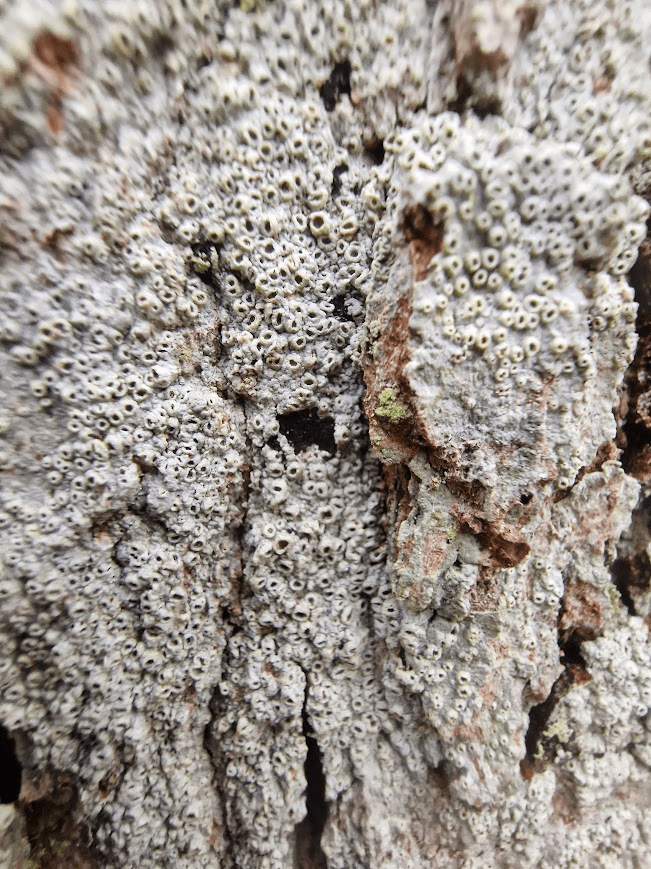

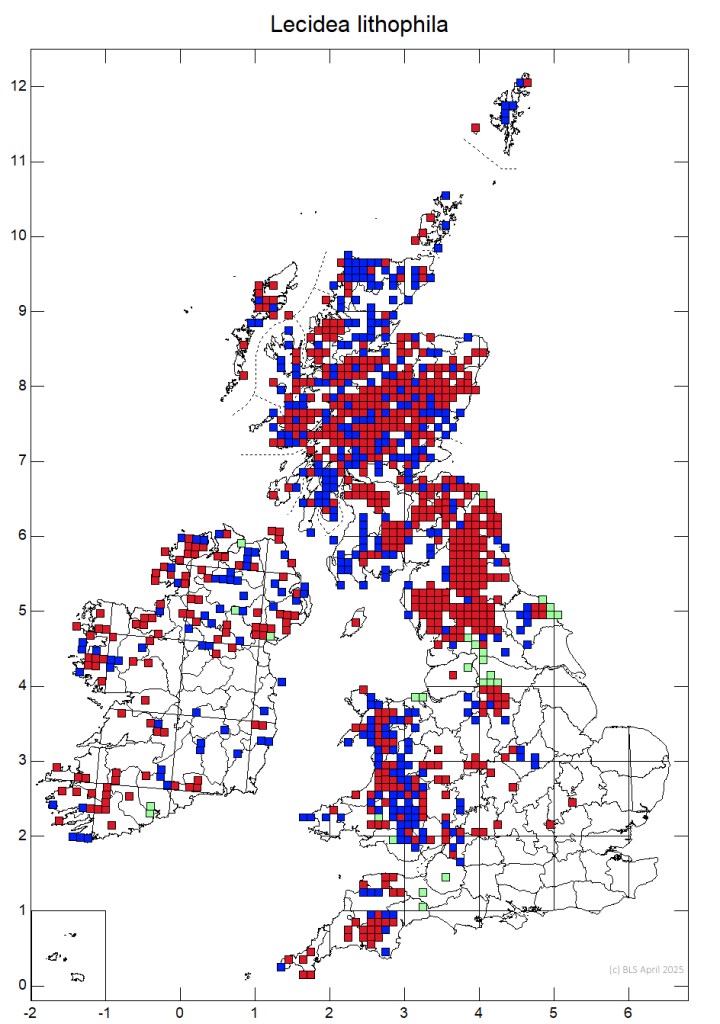

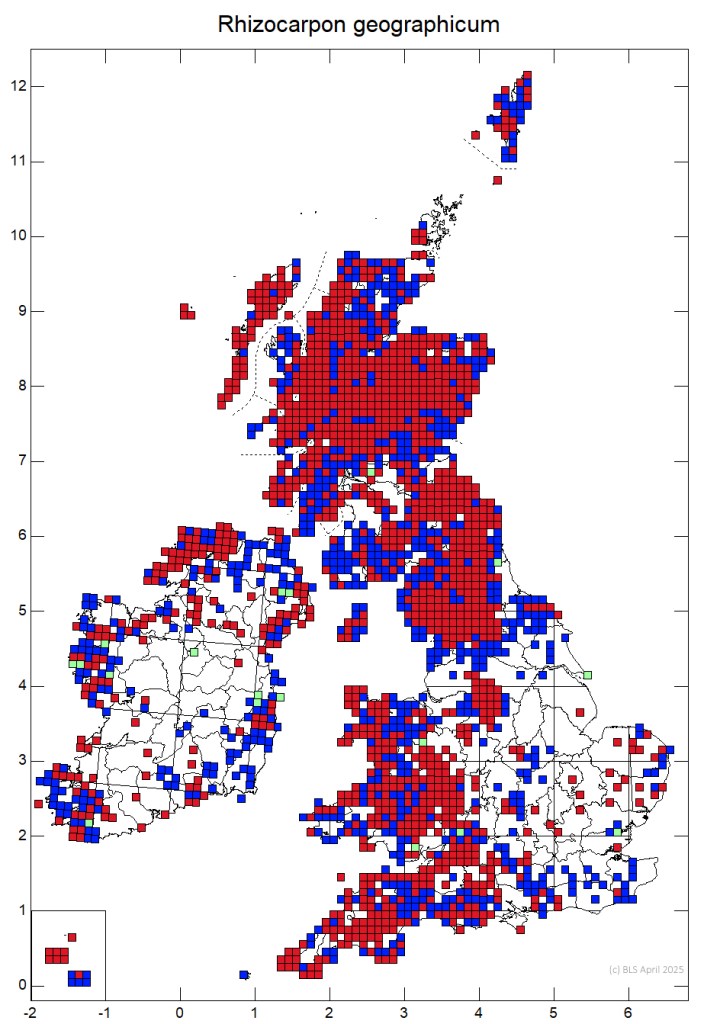

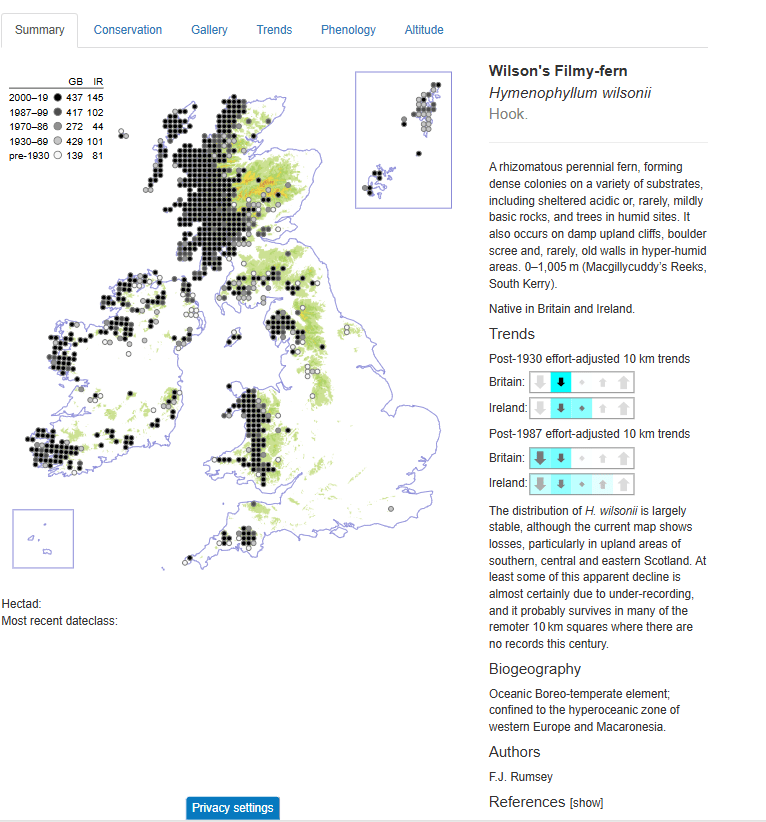

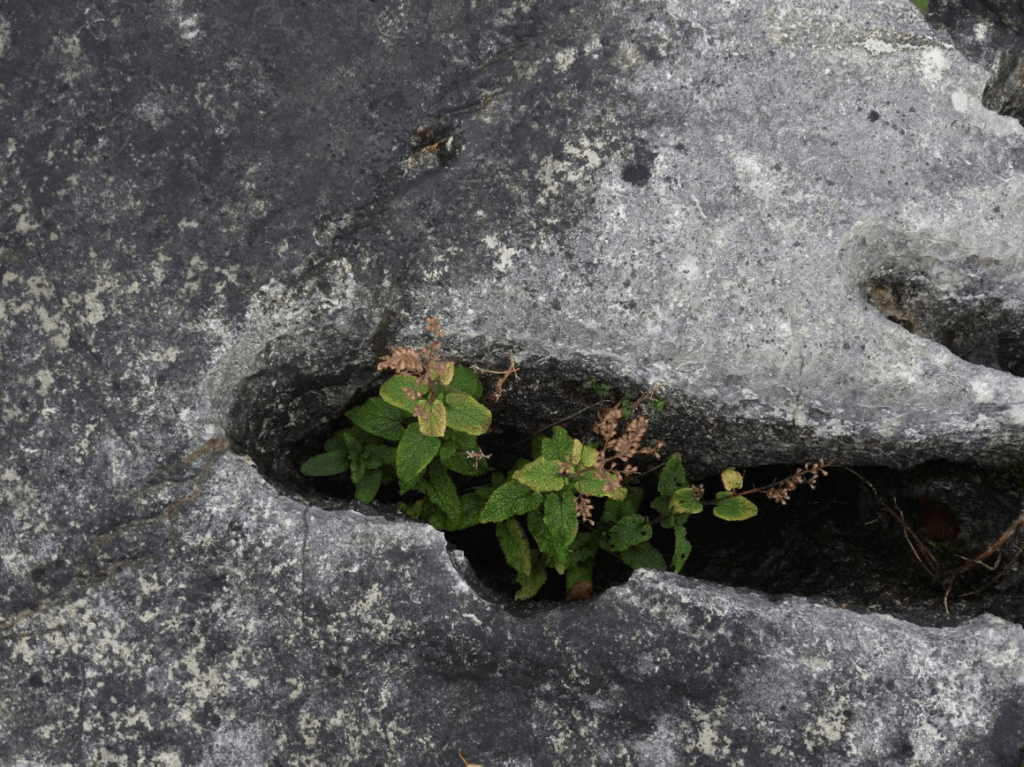

Lichens on this tree:

Oak trees have long had a reputation for supporting a lot of other species but until recently we had no idea just how many and what those species were. Recent work has listed 2300 species associated with oak, of which 320 are only found on oak and a further 229 species are rarely found on species other than oak. James Hutton Institute Decline of Oak

In the Oakhurst (Brookleigh, Countryside Homes, The Hill Group) information kiosk (in show home):

Me: how much is the cheapest house in Oakhurst?

Salesperson: £425,000

The average household income in Burgess Hill is £59,100 p.a. The cheapest house in Oakhurst is 7 x that; more than most mortgage lenders are prepared to lend. The average annual salary of agricultural worker in the South East of England is £25,000. The cheapest house in Oakhurst is 17 x that. In 2023, Andy [Hill, CEO of The Hill Group] remarkable achievements were recognised in the King’s New Year’s Honours List, in which he was awarded an OBE for services to affordable housing. https://www.aru.ac.uk/graduation-and-alumni/honorary-award-holders2/andy-hill#:

Me: I need to think about that.

Salesperson: You’d like it here; its like living in the countryside

The outline planning application was approved by Mid Sussex District Council in October 2019. Brookleigh will deliver approximately 3,500 new homes, 30% of which will be affordable. Delivering Growth & Prosperity, Burgess Hill

The Hill Groups accounts 2023-24

- Turnover: Reached a record £1,145.9 million (compared to £716.1 million in 2022).

- Profit Before Tax: A record £70.1 million (compared to £65.6 million in 2022).

- Net Assets: Increased to £368.9 million as of March 31, 2024.

- Net Cash: £86.4 million, with £70 million drawn from a £220 million revolving credit facility.

- Operational Performance: Delivered 2,886 homes during the period.

- Development Pipeline: Stands at over 27,000 units, with a potential revenue exceeding £10 billion. https://www.reports.hill.co.uk/annual-review/2023-24/financial-overview/

Andy Hill’s, the CEO of the Hill Group, personal wealth is estimated at £520 million. And he has re-entered the UK rich list. Building.co.uk https://www.building.co.uk/news/familiar-names-on-rich-list-as-housebuilder-remains-constructions-wealthiest-man/

Building Oakhurst:

David Gladwell’s 1975 film Requiem for a Village, a poetic meditation on how the modern world’s rapid acceleration buries the past and with it the traditions, skills and knowledge that were at the heart of British life and its relationship to the landscape and countryside. Frank Collins 2011 British Cult Classics – Requiem for a Village / BFI Flipside Blu-ray Review

The film is currently available from on BFI Player (subscription required)

The destruction of the rural landscape of the Low Weald started with the coming of The London & Brighton railway, resulting in large population growth. The building of the railway started in 1838 and cut through several farms including Peppers Farm in Lye Lane (Leylands Road), Yew Tree Farm, Anchor Farm and Burgess Hill Farm. Between 1850 and 1880 the area changed from a relatively quiet rural backwater into a country town with a population of about 4500. … From 1952, when Second World War (1939-1945) controls on building were lifted, and strict planning and building regulations came into force, large scale expansion once more began. This process has continued with no significant break to the present time. The population almost doubled to 14,000 between 1951 and 1961. Much of Burgess Hill’s residential housing dates from this time History of Burgess Hill, Burgess Hill Town Council retrieved 23.01.2026. Of late, the amount of development in the countryside around Burgess Hill has accelerated greatly, and will increase further with Labour’s obsession that empowering private developers to build, build, build, will produce affordable housing. It has not done so but Labour has facilitated building property developers; profits.

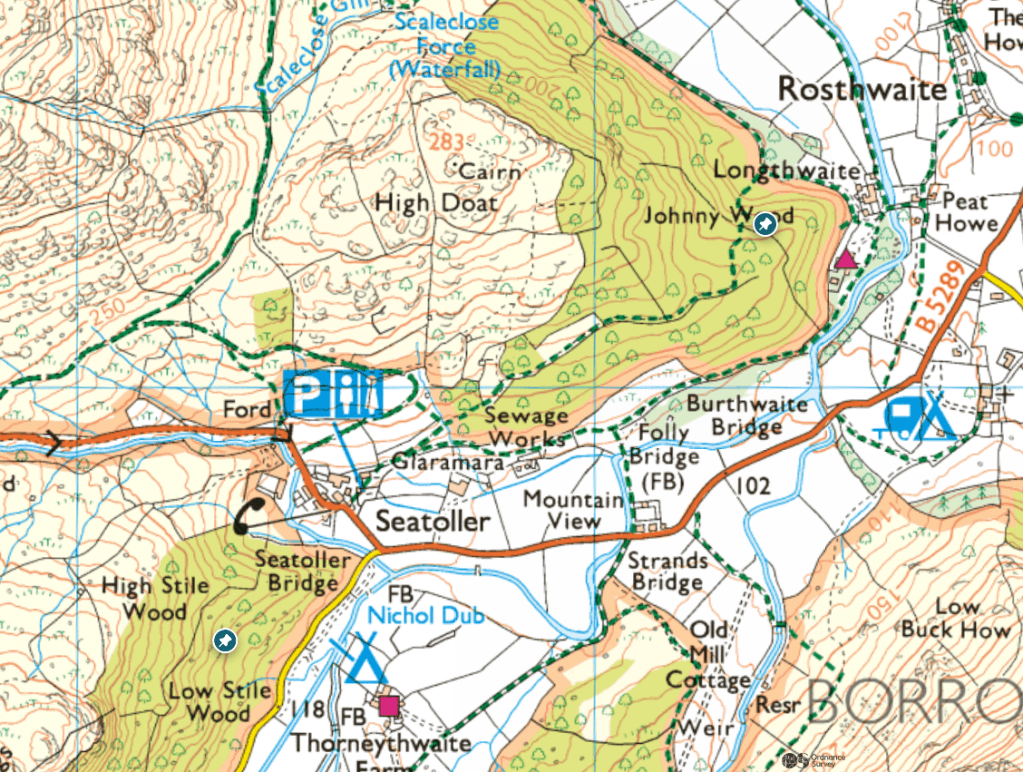

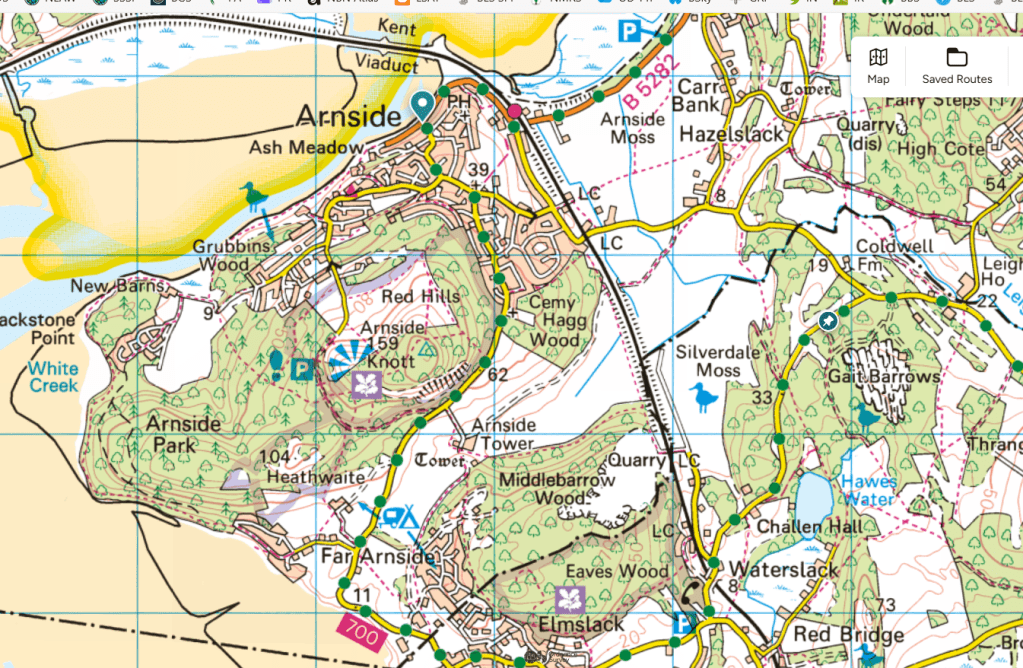

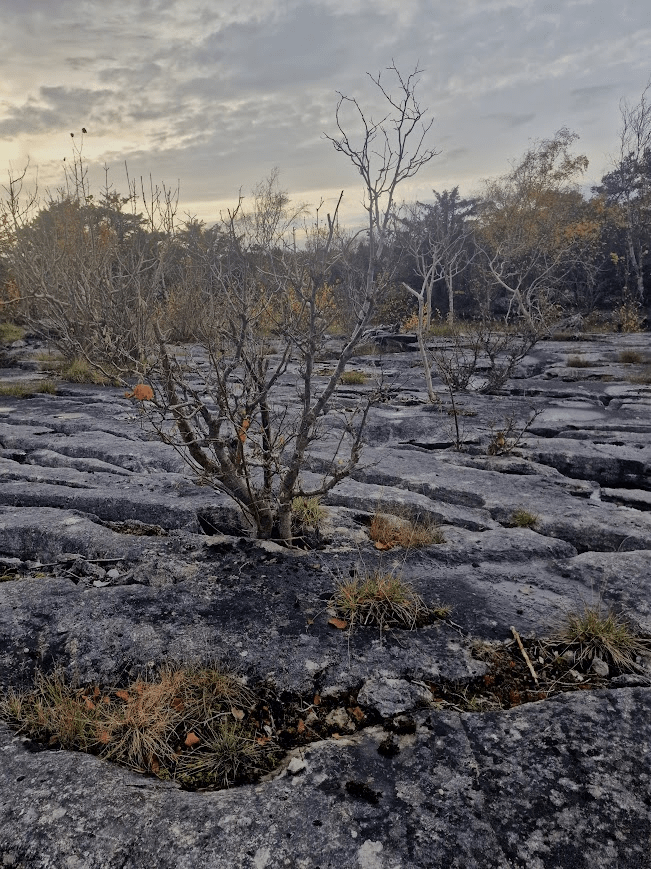

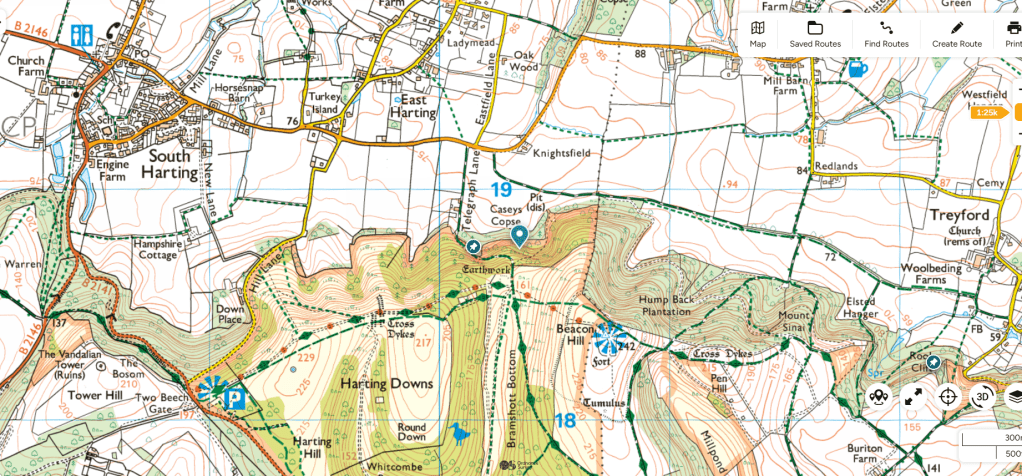

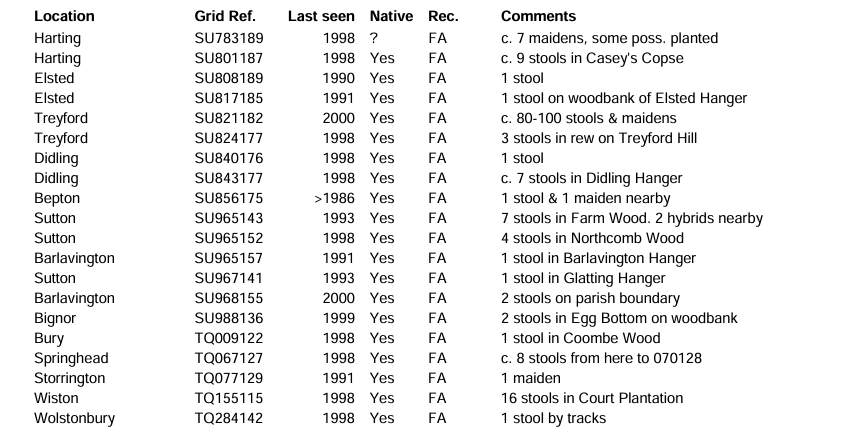

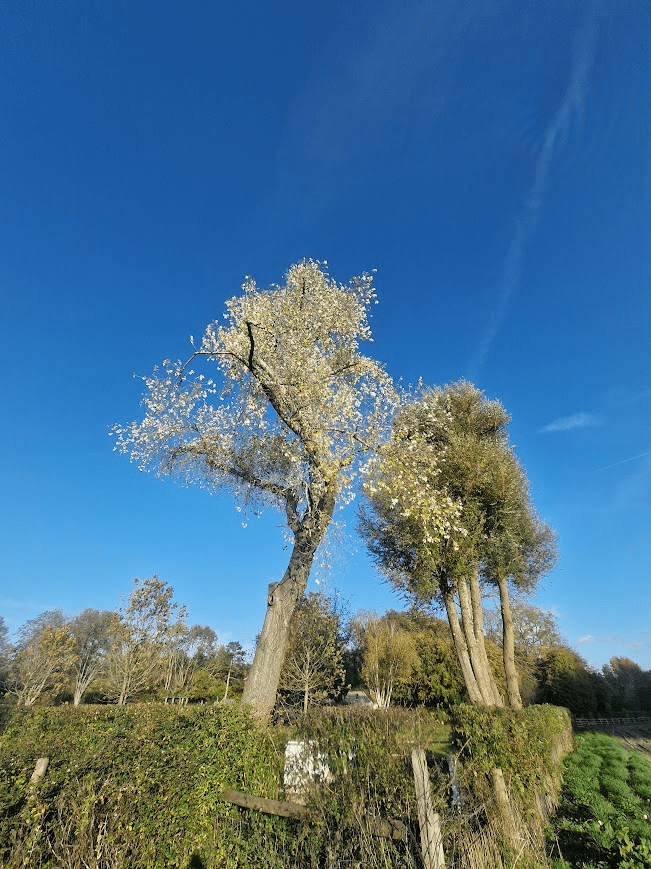

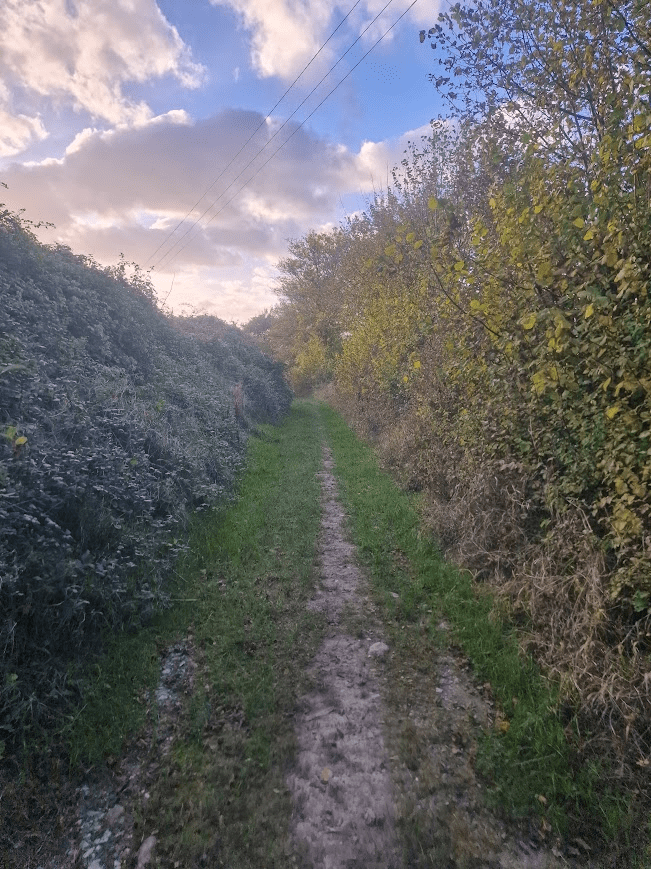

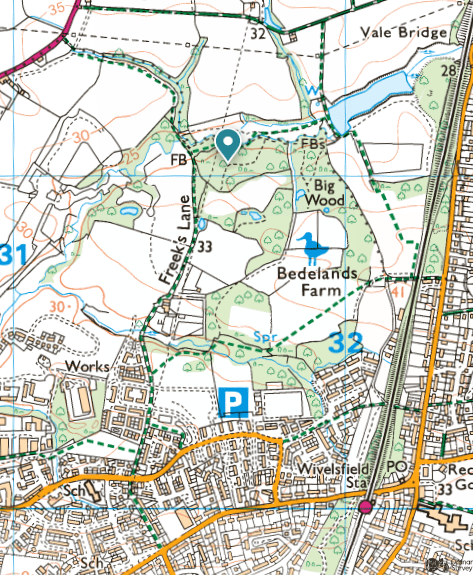

Today I walked along Freek’s Lane to the Oakhurst Estate; currently being built with some show homes open to view. But I could only get so far as the footpath (right of way), a former Roman Road – lined with hedgerow with superb ancient Pedunculate Oak – was closed to facilitate the building of the estate.

A restored barn nearby at Lowlands (formerly Freeks) – a name derived from the local rough woodland or Ferghthe as it was spelt when the land was first settled in the Anglo-Saxon period.

All the land on the east part of the town, east of Keymer Road and Junction Road, was … . all part of the great wood of Frekebergh which stretched north to what is now Worlds End. It was privately owned and actively managed by the lords of Keymer and Ditchling manors. The earliest farms they allowed (from around 1250 onwards) were on either side of Folders Lane and along the edge of Ditchling Common. The rest remained as woodland and coppice for much longer. A small farm lay at its northern end, its land reaching up as far as Janes Lane, which the lord of the manor kept in hand. It was mentioned in 1580 as having ‘a little house’ in it and its old well is still there in two front gardens in Stirling Court Road. This connection with the lord of the manor gave rise today to the local school name, ‘Manor Field’. Old hedgerow oaks, remnants of this once enormous wood of Frekebergh are still a strong feature within the St. Andrew’s Road housing estate. A small brick and tile business had grown up by the early 1700s on a site near the top of Cants Lane – at a slight remove from where the Keymer Brick and Tile Company was later developed. Burgess Hill Heritage and History History Association: Earlier History

The are only a few fragment of the Frekebergh Wood left; one being the Bedelands LNR Big Wood (which is a minuscule fragment of the Anglo-Saxon wood). Until recently much of the area around Freek’s Lane was woodland and wet meadow. Now much of the land around the lower part of Freek’s Lane is homogenous, hideous, unaffordable housing for the rich

Freek’s Farmhouse Burgess Hill Heritage and History History Association: Earlier History

The housing developments that are currently being undertaken around Burgess Hill include:

- Oakhurst at Brookleigh (Countryside Homes): Features 2, 3, and 4-bedroom homes designed for modern, energy-efficient living.

- Brookleigh (Northern Arc): A massive, long-term development on the north side of town, incorporating new schools, community infrastructure, and road improvements.

- Fairbridge Way (Places for People/Ilke Homes): A 307-home development focusing on sustainable, factory-built

- Kings Way (Persimmon Homes): A 480-home site in development with 30% affordable units,

- Kings Weald (Croudace Homes): Located at the former Keymer Tiles site, this 475-home project is well advanced, with phases 1 and 2 completed and phase 3 in progress.

- Templegate (Thakeham): Located between Keymer Road and Folders Lane, offering 2-4 bedroom homes

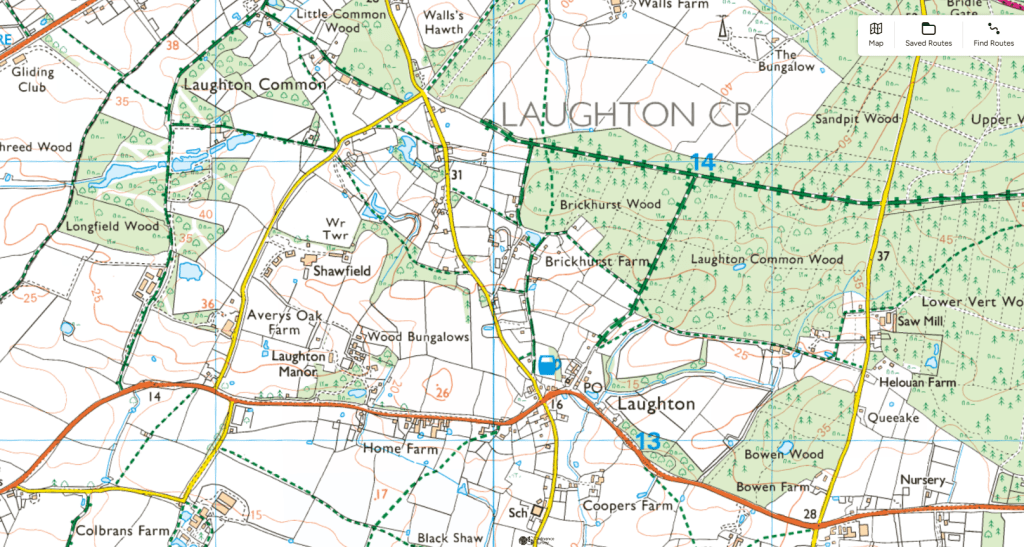

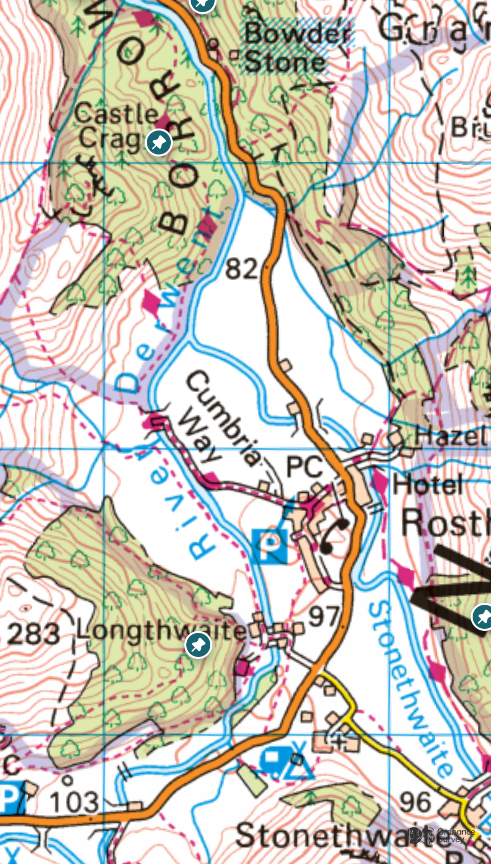

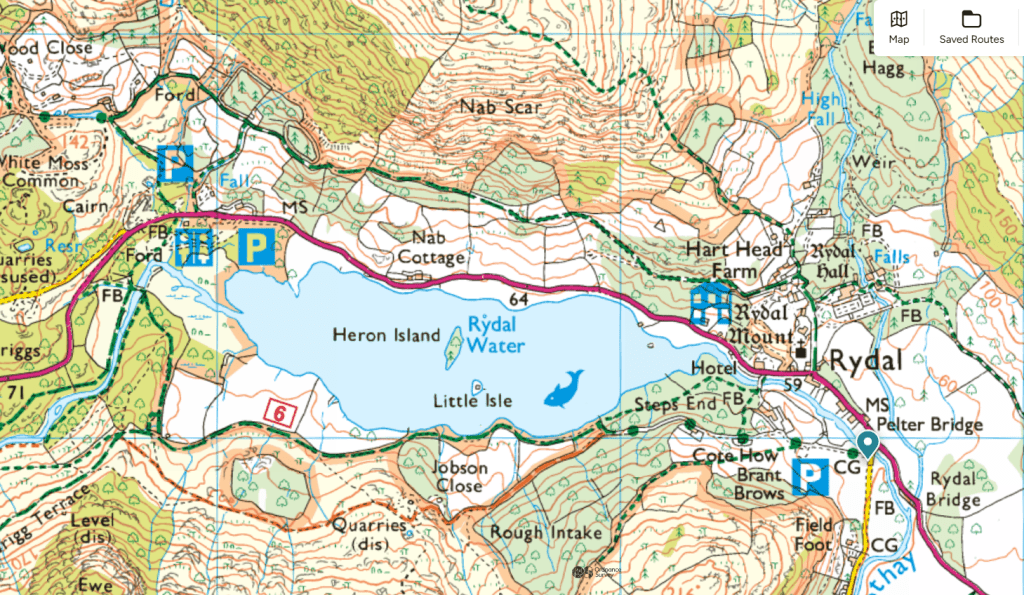

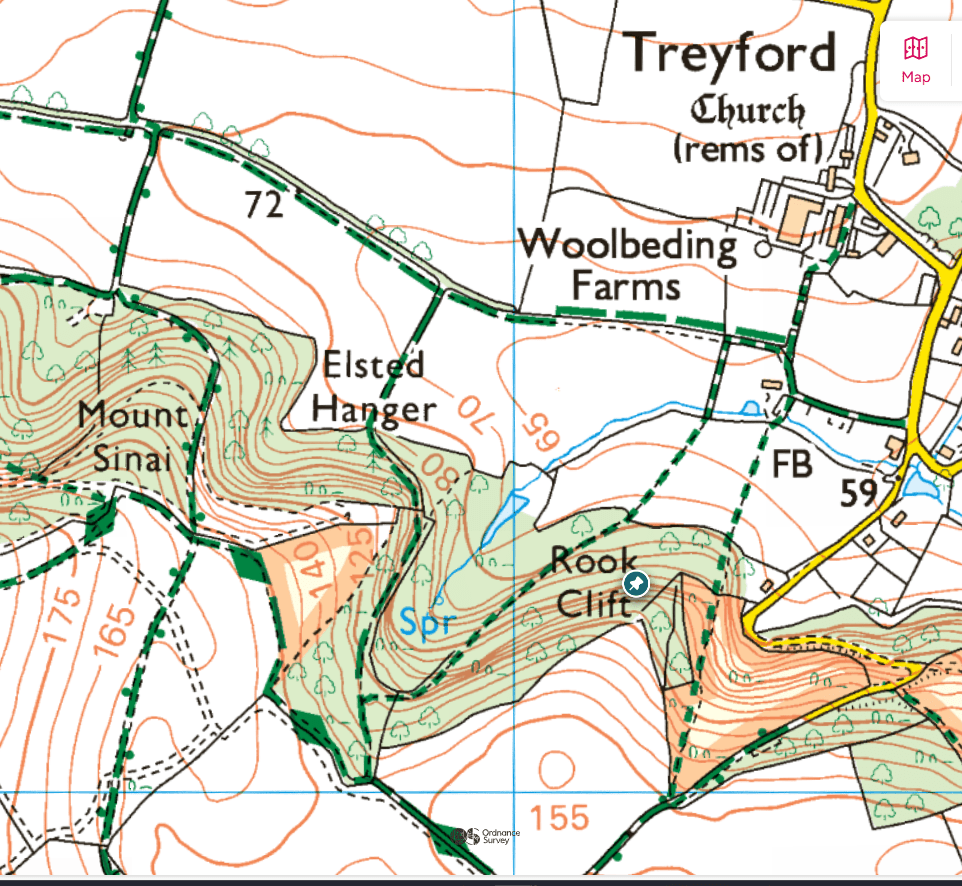

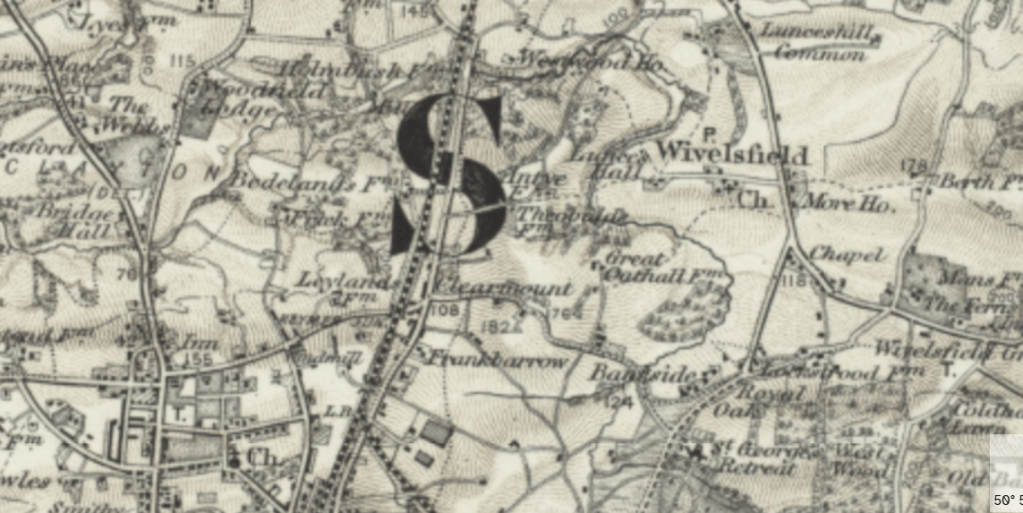

The Ordnance Survey Map, for 1872-1914 shows the former woodland and farmland around the railway line. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/

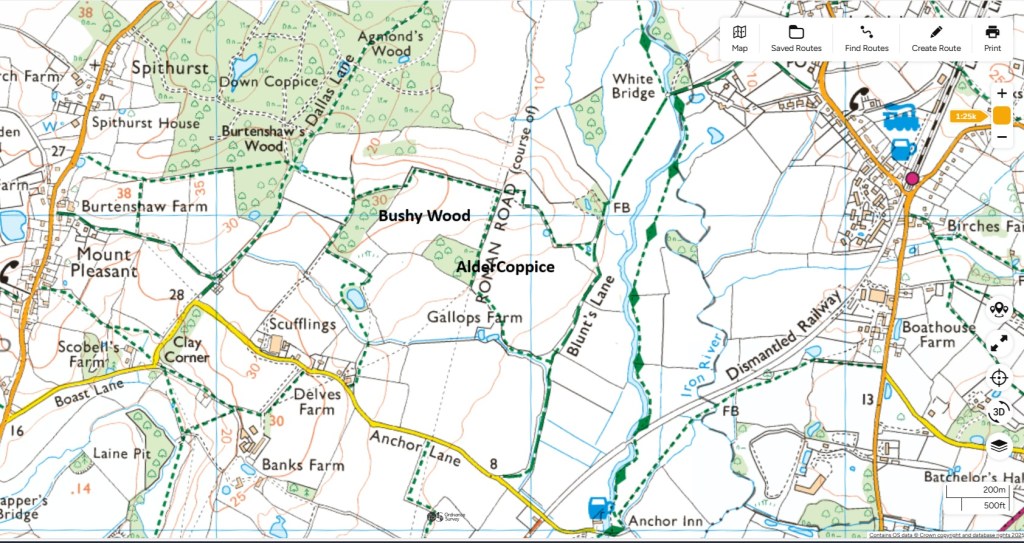

What was left of farm and woodland around 20 years ago

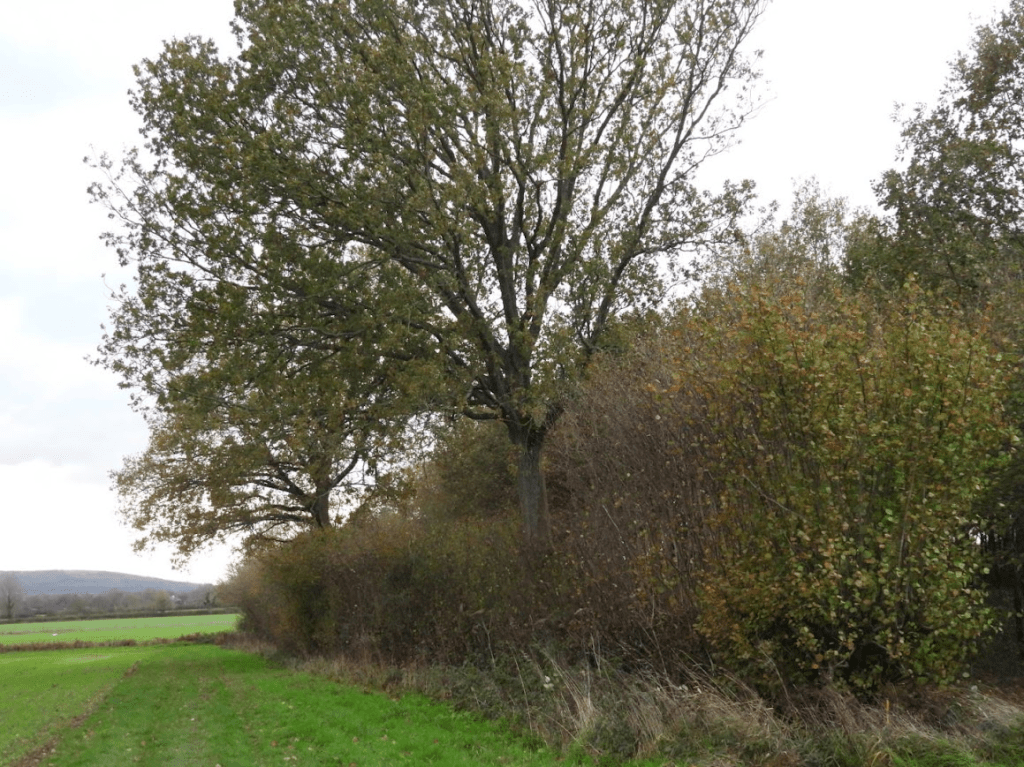

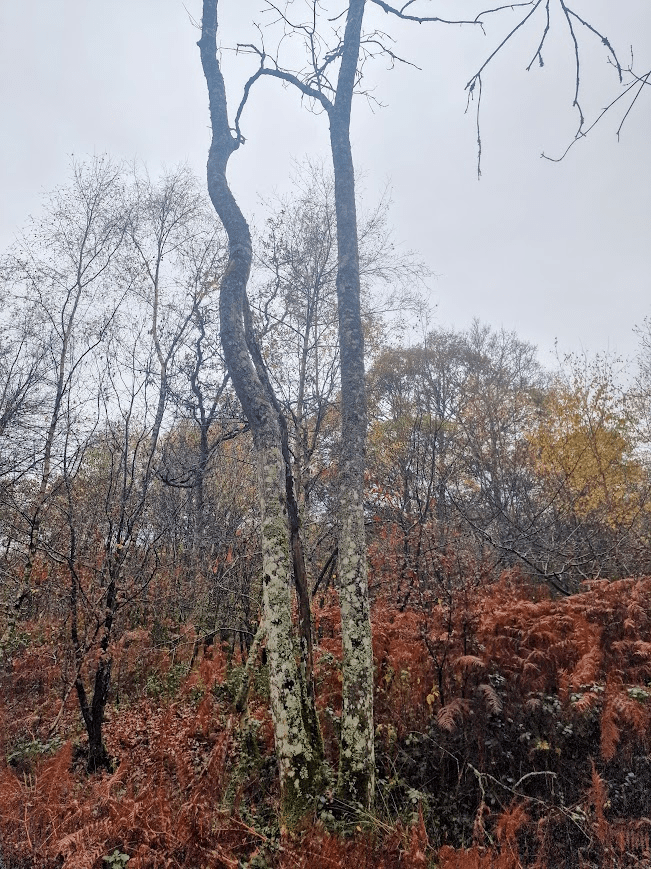

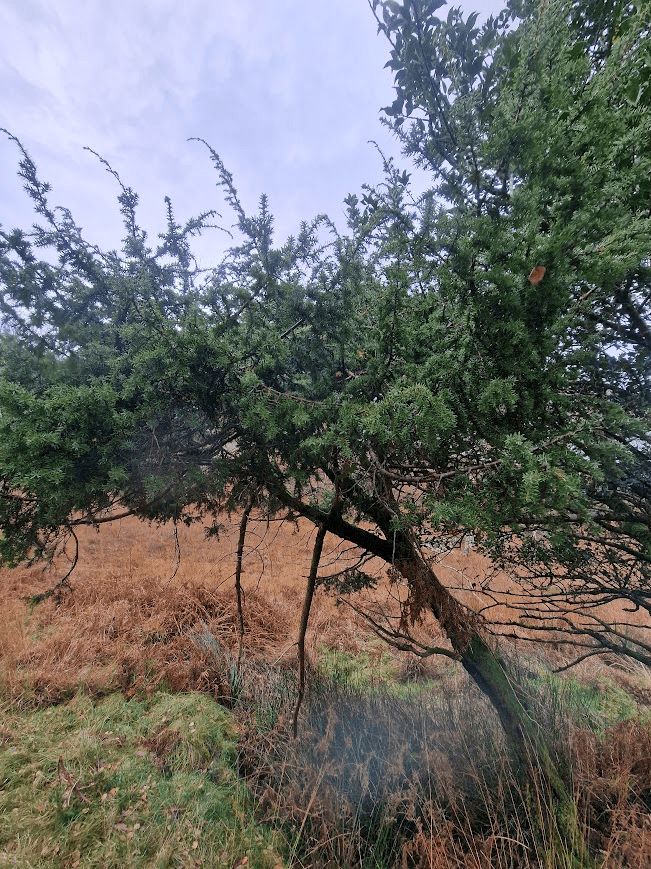

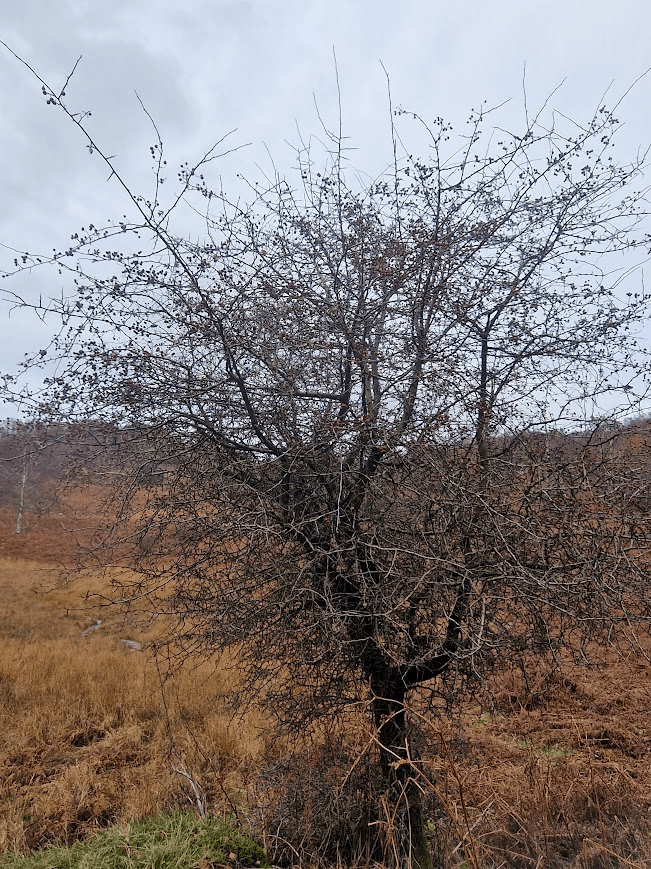

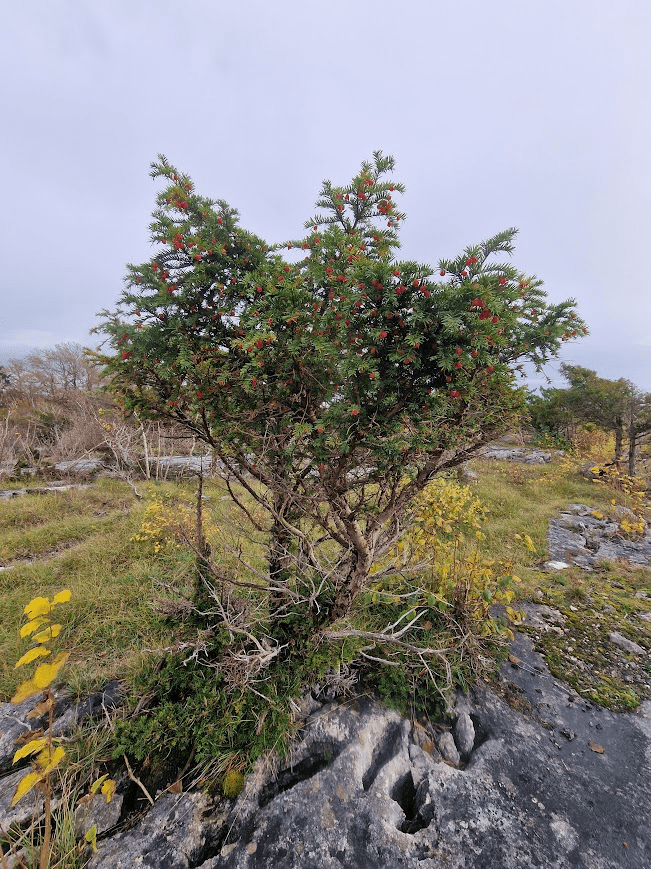

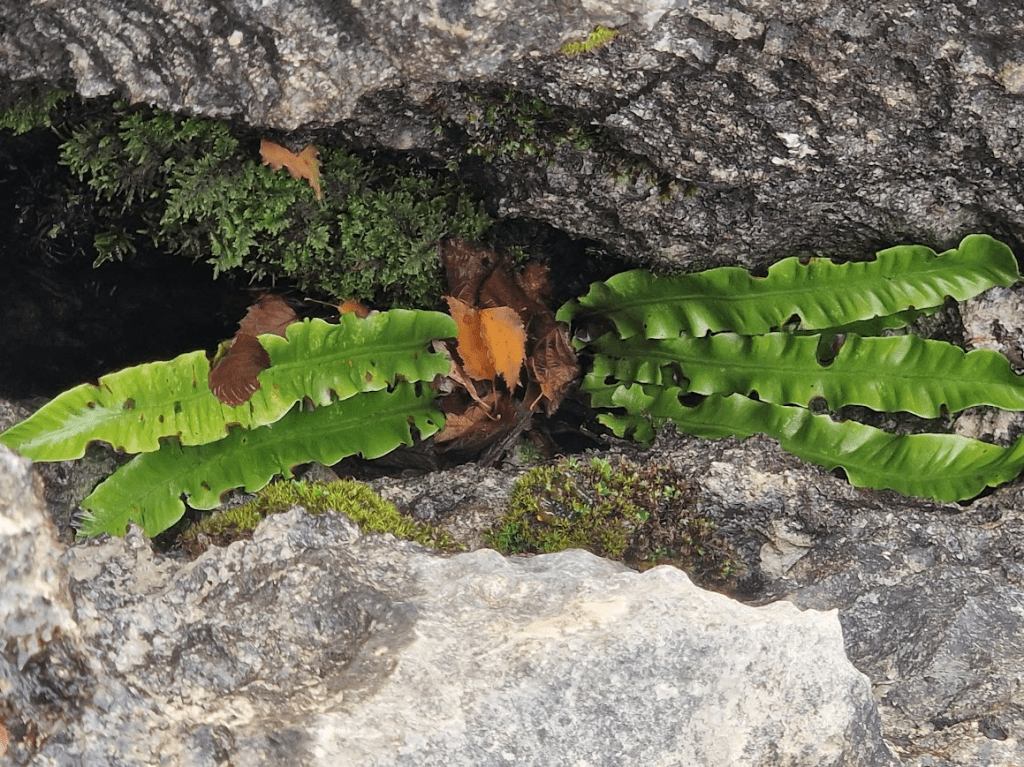

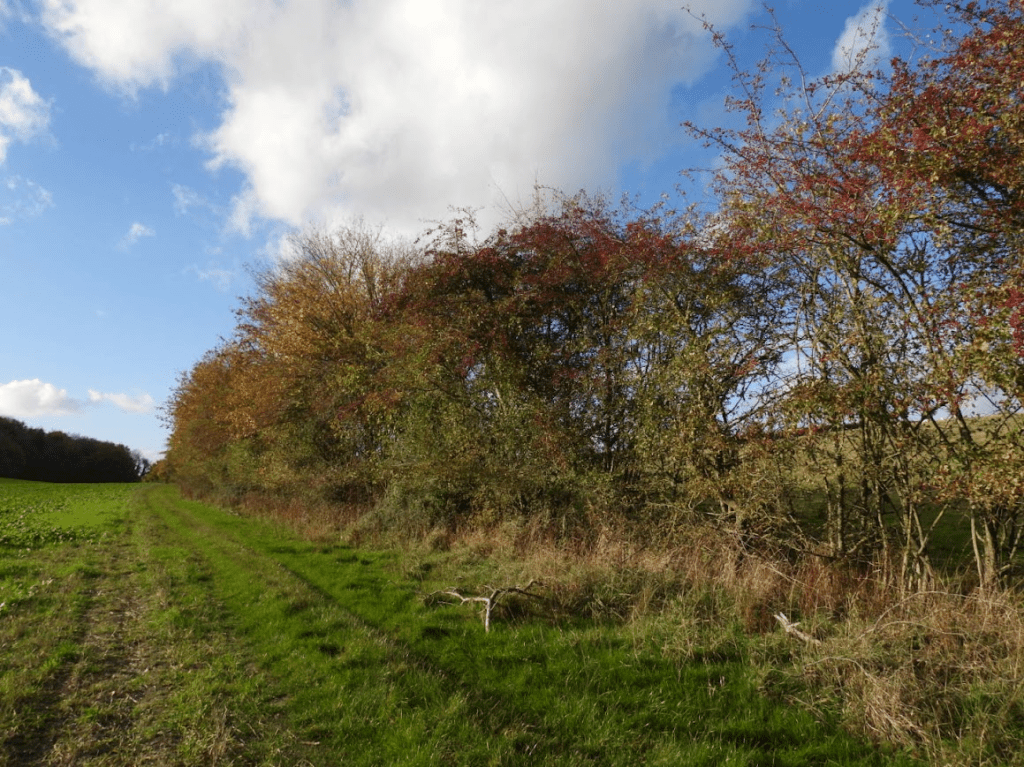

Surviving relicts of this wooded landscape:

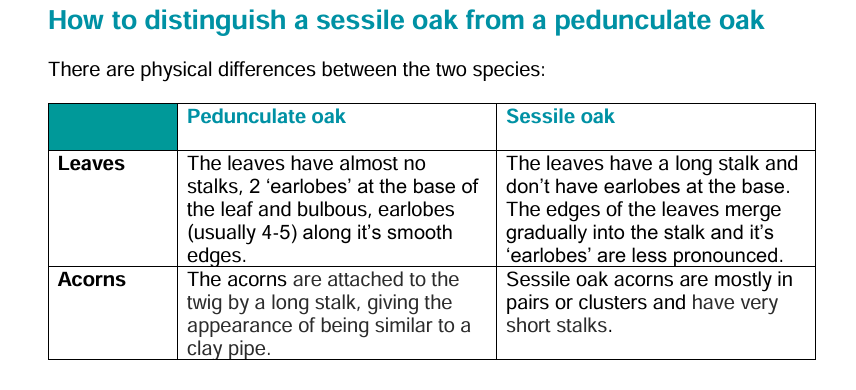

Medieval hedgerow with Hornbeam, Pedunculate Oak and Wild Service trees. (Bedelands LNR)

Bedelands retains a little of what has been lost.

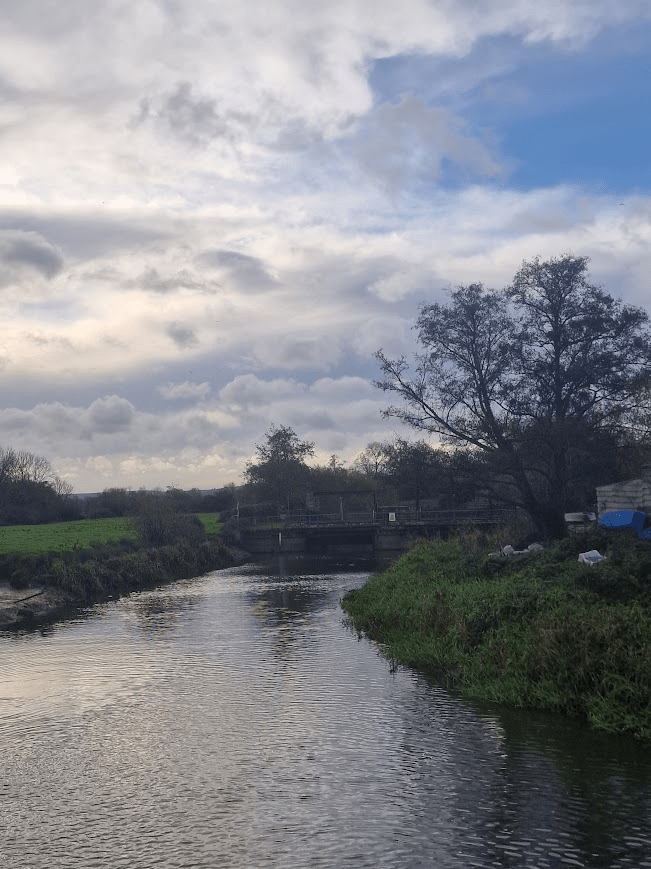

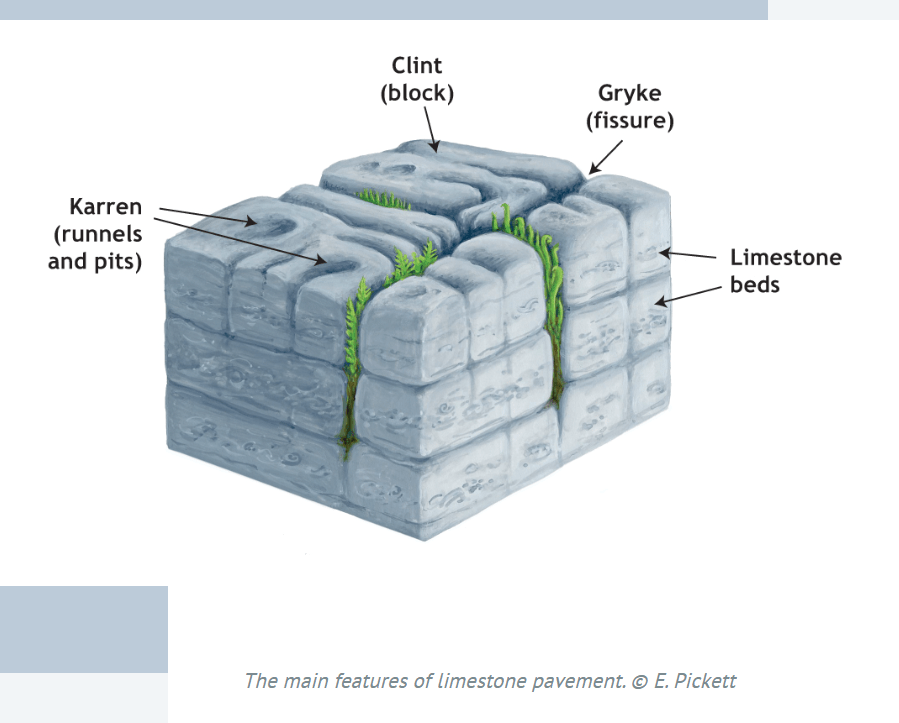

Bedelands and Freek’s Farm’s meadows, lags (wet meadows), ancient woods, riverine hangars and glades have magic most of all where the Roman road fords the young Adur, TQ 316 211. It is just as the Romans would have known it, though the only emperors to be seen are Emperor Dragonflies, with red and blue damsels, and Beautiful and Banded Demoiselles.

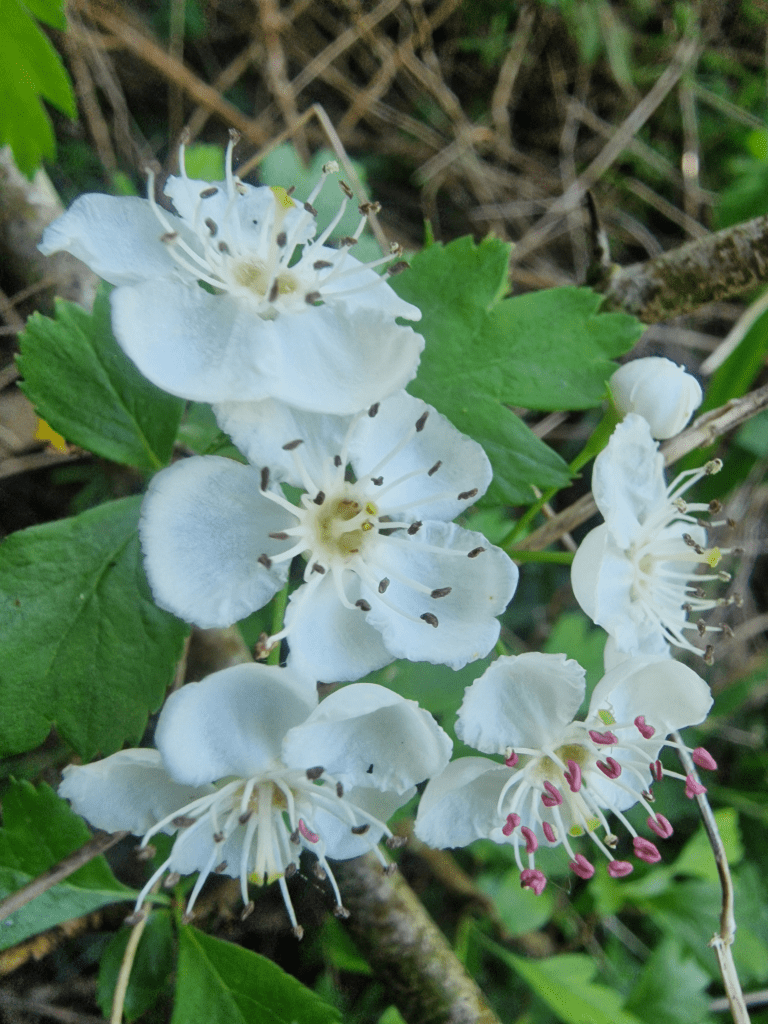

Heavy, May-scented Wild Service blossoms overhang the almost-stilled little river that is guarded by steep, wooded clay banks above grassy riverside plats. It only lacks Wild Boar prints in

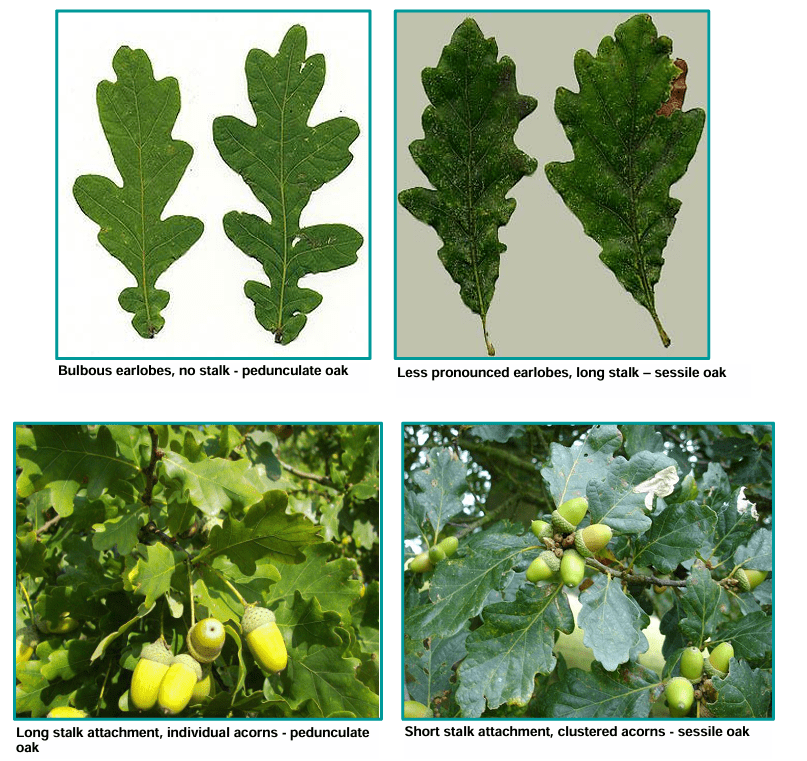

In Freek Farm Wood, TQ 316 210, overlooking the fording, the Wild Service Tree is the most frequent remember seeing it, clustered along the bank top. All around in the wood are very tall Sessile Oak poles. I am used to seeing Sessile Oak woods in the High Weald… but here? in the Wealden clay vale? The wood has been managed for its Oaks, though there are remnants of struggling coppice of Hazel, Hornbeam and Holly. It is a shady, tranquil wood of Bluebell and Anemone with many other old woodland plants, like Field Rose on the boundary with Freek’s Farm meadow, TQ 316 209, which is archaic and colourful,

Big Wood, Watford Wood, Long Wood, and Leylands Wood, all on the neighbouring Local Nature Reserve, have many of the qualities of Freek Farm’s woods, but benefit from the management of the District Council and the Friends of Burgess Hill Green Circle. The Bluebells of Big Wood are a wonder.

Freek’s Lane is the direct descendant of the ramrod straight it to weave in more relaxed fashion between huge old straight Roman road, but 1,800 years of traffic have led it to weave in more relaxed fashion between huge old oak trees and rich hedgerow. They prompt no complaint from me. I feel blessed to have spent time there, and angry that anyone even think of building on any of this complex, rich and ancient landscape (2013). Dave Bangs2018 Bedelands and Freek’s Lane’s Meadows and Wood Between Hayward’s Hath and Burgess Hill in The Land of the Brighton Line: A field guide to the Middle Sussex and South East Surrey Weald pp. 222-223

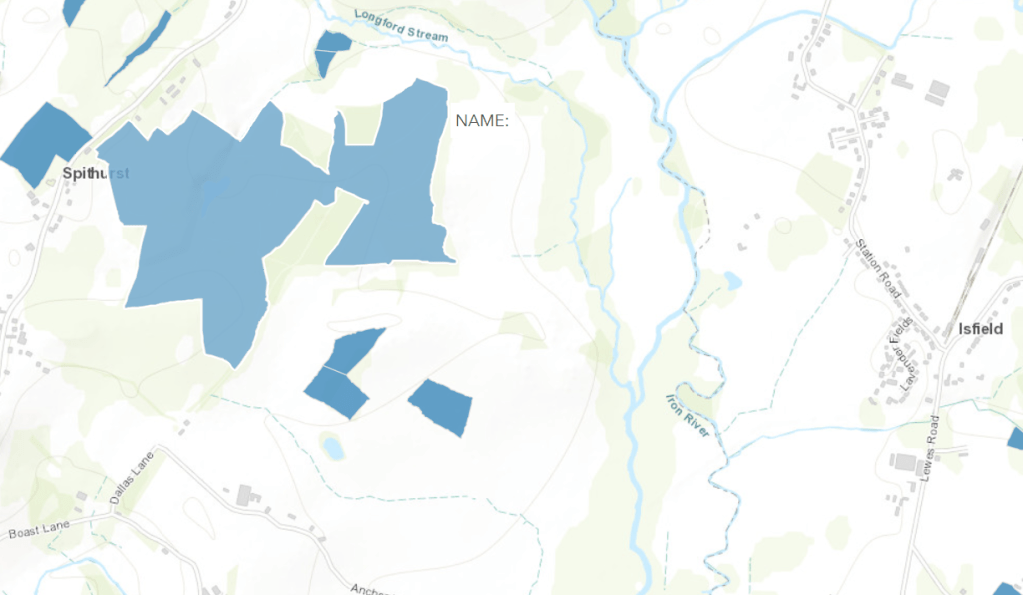

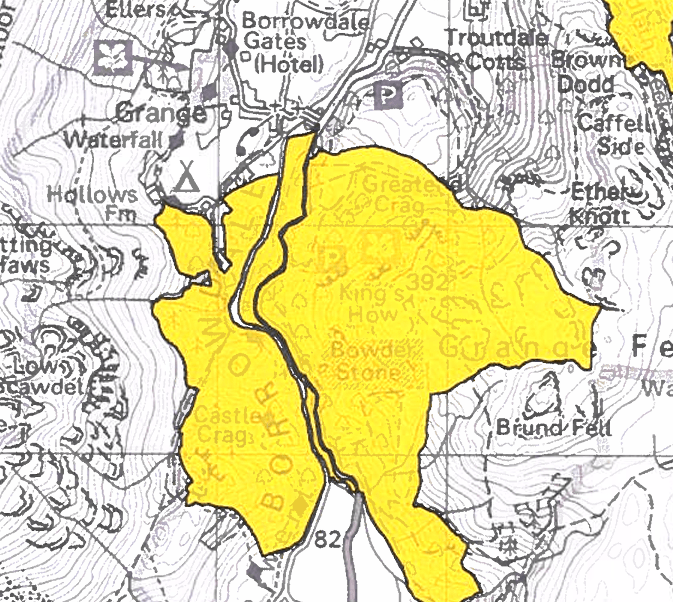

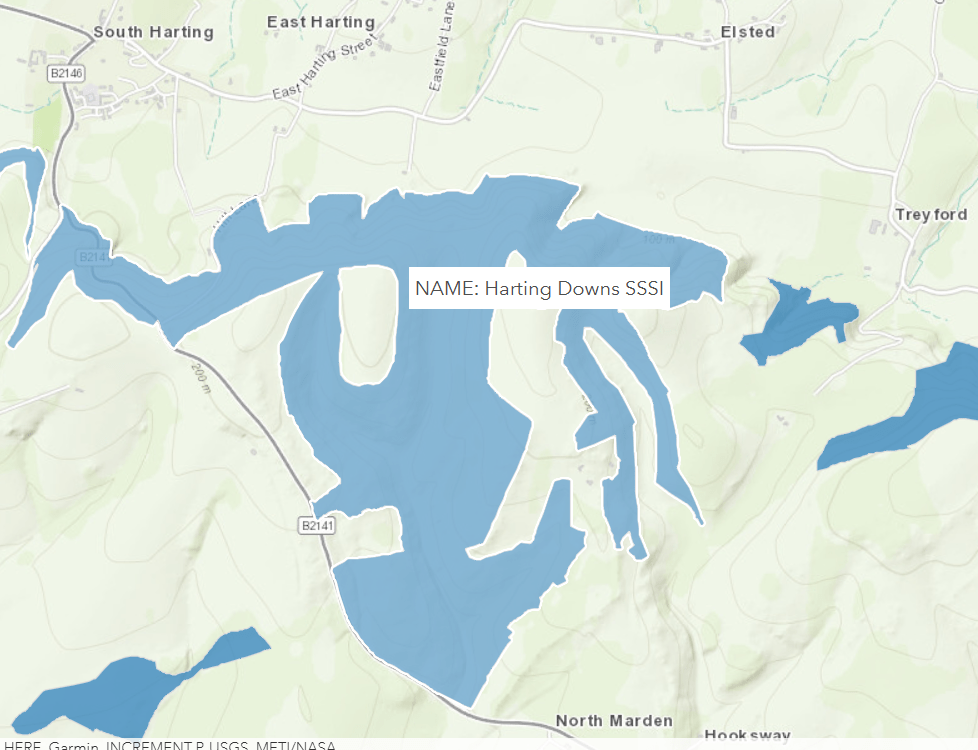

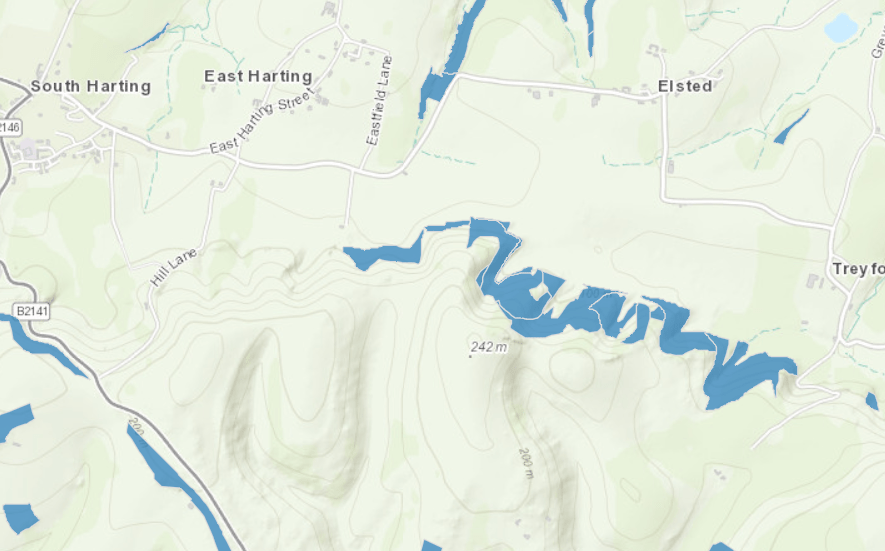

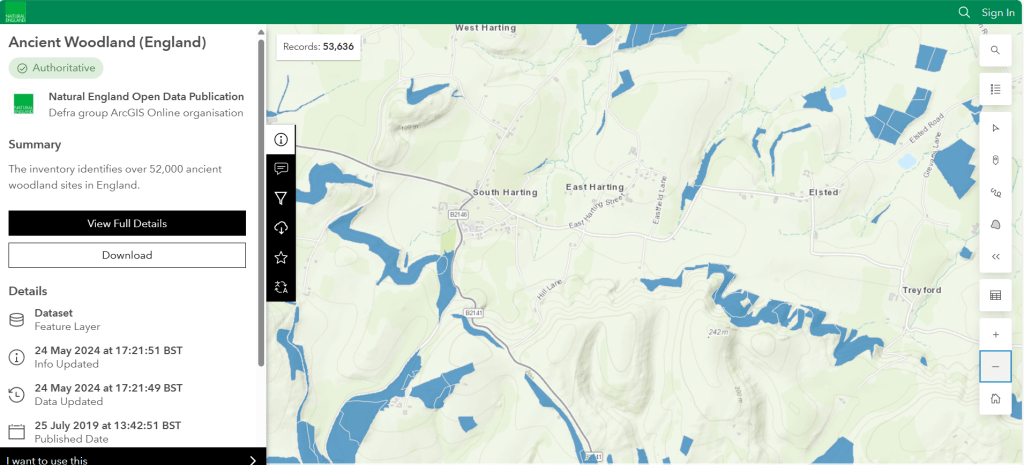

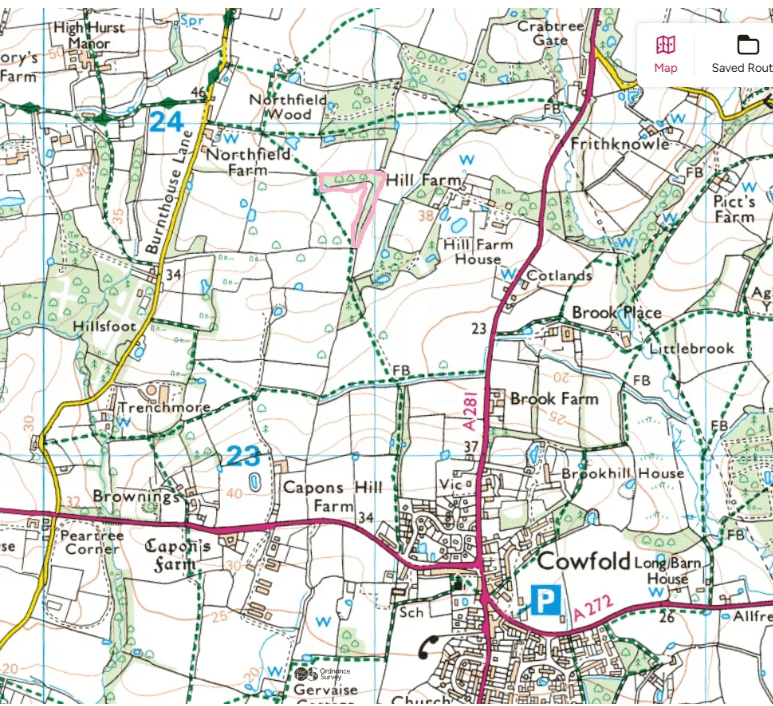

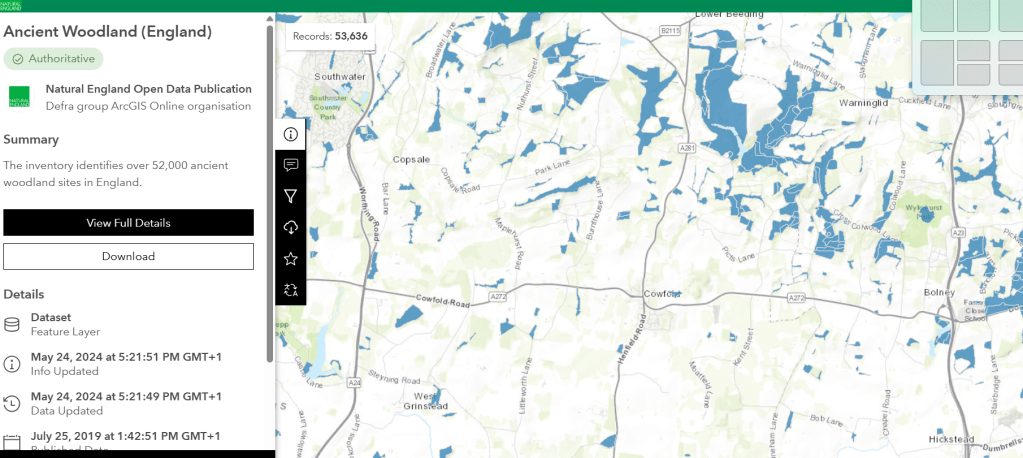

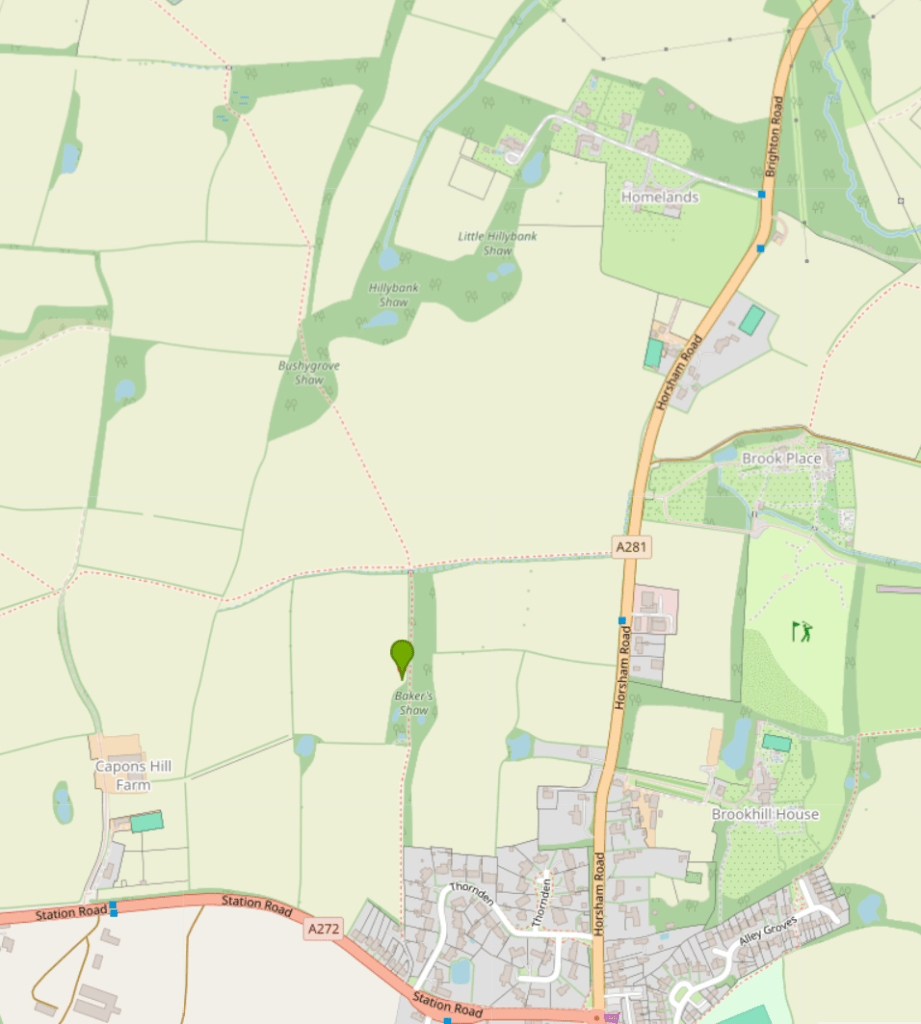

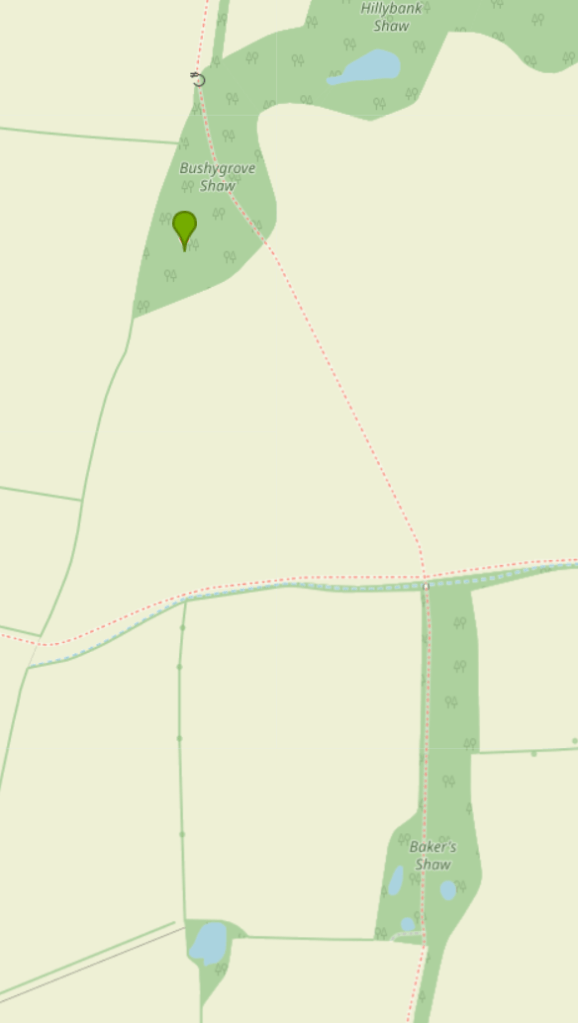

It is the farmland to the west of Freek’s Lane that is being built upon. The ancient woodland of the Big Wood (Bedelands Farm LNR) and Freek’s Farm Wood (marked with a flag) will be squeezed between the existing housing east of the railway line and the new development west of Freek’s Lane

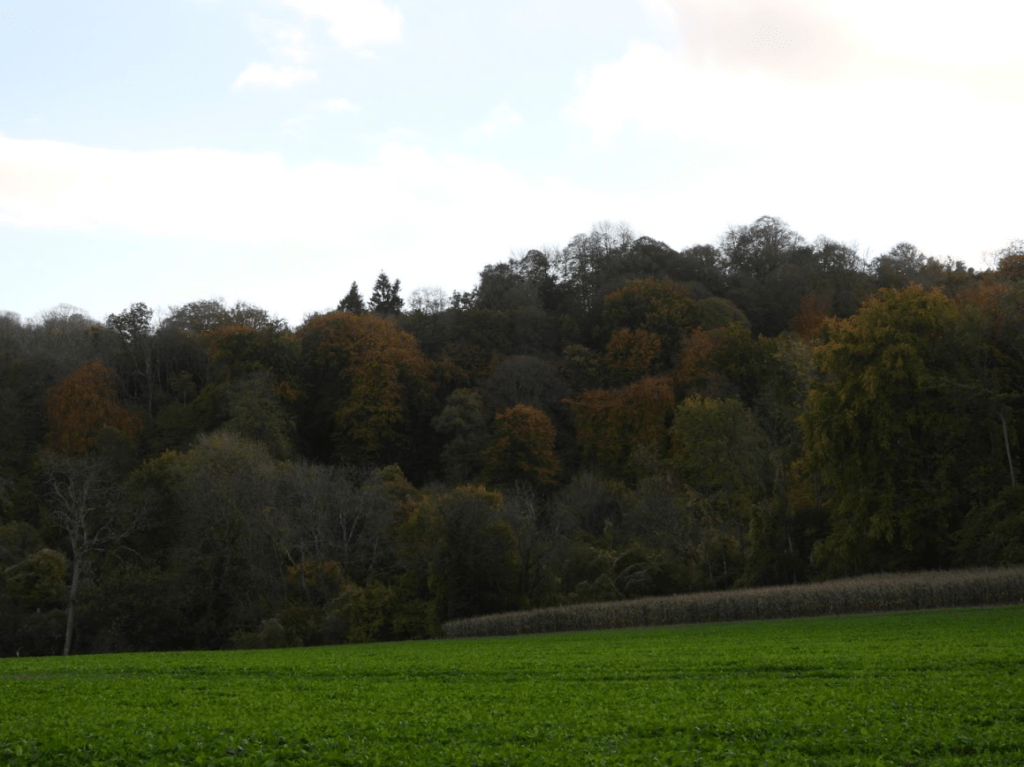

Woodland around the top of Freek Lane; Freek’s Farm Wood

MID SUSSEX DISTRICT COUNCIL DISTRICT WIDE PLANNING COMMITTEE

4 OCT 2018 extract

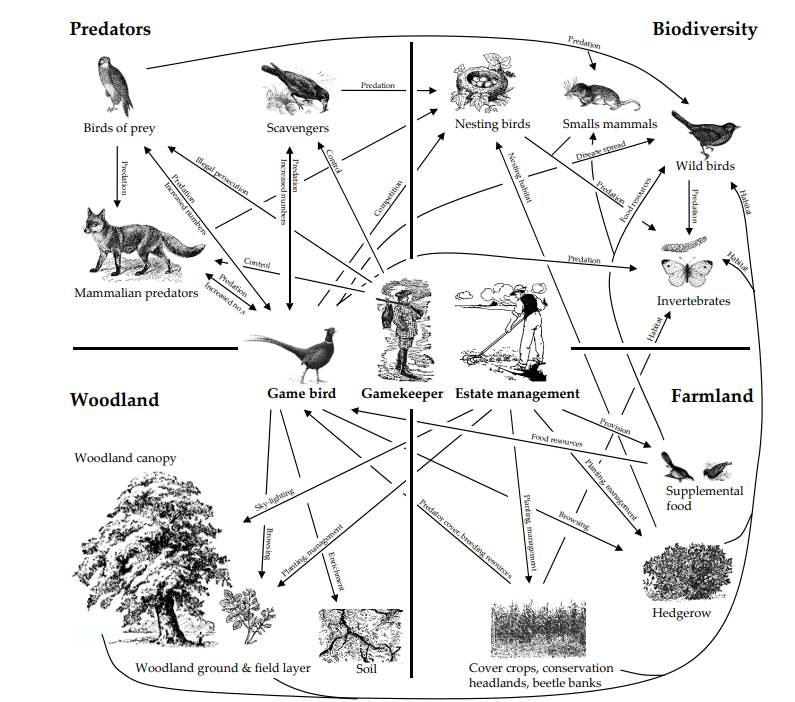

The Councils Ecological Consultant goes on to state “There is likely to be a need for protected species licensing from Natural England for a range of species. However, subject to appropriate mitigation design then, if MSDC considers there to be an overriding public interest case for granting consent (including reasons of a social or economic purpose), then it is likely, in my opinion, that licences will be obtainable.” Given the fact that this site is allocated for housing development this is a clear case where there is an overriding public interest in granting consent.

The Councils Ecological Consultant has advised that there will be additional visitor pressure on Bedelands Local Nature Reserve and that mitigation for this may need to include financial contributions to assist in its management and monitoring of visitor pressure. It is considered that this could be properly controlled by a planning condition that requires details of a management plan to be submitted to the LPA for approval. If the management plan requires off site works at Bedelands Local Nature Reserve (which might involve financial contributions) there should be no reason why these can’t be carried out because the District Council is the landowner of Bedelands.

The Councils Ecological Consultant concludes by stating that in his opinion, there are no biodiversity policy reasons for refusal, subject to conditions. Your officer has no reason to dispute his conclusions. It is considered that a suitably worded condition can ensure that the necessary ecological protection, mitigation and compensation measures are provided thus complying with policies DP37 and DP38 in the DP and the aims of the SPD’s in the Masterplan.

So even if you disregard the value of the farmland to be built on, the development will impact upon protected species and will add visitor pressure on Bedelands Nature Reserve (an island of ancient woodland in the middle of urbanization) but according to Mid Sussex District Council this is a clear case where there is an overriding public interest in granting consent.

What is the public interest in building homes that no-one in Burgess Hill can afford and enrich already rich property developers at the expense of nature and farm land? If the state itself was building social housing for social rents there may be a public interest to build on farmland.

Local and central government disregard for nature was written about by Larkin in 1972

Going, Going, Philip Larkin, 1972

I thought it would last my time –

The sense that, beyond the town,

There would always be fields and farms,

Where the village louts could climb

Such trees as were not cut down;

I knew there’d be false alarms

In the papers about old streets

And split level shopping, but some

Have always been left so far;

And when the old part retreats

As the bleak high-risers come

We can always escape in the car.

Things are tougher than we are, just

As earth will always respond

However we mess it about;

Chuck filth in the sea, if you must:

The tides will be clean beyond.

– But what do I feel now? Doubt?

Or age, simply? The crowd

Is young in the M1 cafe;

Their kids are screaming for more –

More houses, more parking allowed,

More caravan sites, more pay.

On the Business Page, a score

Of spectacled grins approve

Some takeover bid that entails

Five per cent profit (and ten

Per cent more in the estuaries): move

Your works to the unspoilt dales

(Grey area grants)! And when

You try to get near the sea

In summer . . .

It seems, just now,

To be happening so very fast;

Despite all the land left free

For the first time I feel somehow

That it isn’t going to last,

That before I snuff it, the whole

Boiling will be bricked in

Except for the tourist parts –

First slum of Europe: a role

It won’t be hard to win,

With a cast of crooks and tarts.

And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There’ll be books; it will linger on

In galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres.

Most things are never meant.

This won’t be, most likely; but greeds

And garbage are too thick-strewn

To be swept up now, or invent

Excuses that make them all needs.

I just think it will happen, soon.

Larkin predicts the Grey Belt; not an actual policy until Labour invented it: Labour’s “grey belt” policy, introduced in 2024, identifies low-quality, “under-utilised” areas within the protected Green Belt—such as disused car parks, neglected scrubland, and petrol stations—for accelerated housing development. This strategy aims to deliver up to 200,000 homes by easing planning restrictions on these specific sites. BBC 8 July 2024 What is the ‘grey belt’ and how many homes could Labour build on it?

In practice, the government’s “grey belt” policy has not been about building on petrol stations but an existential threat to the protections of the Green Belt. Our latest research shows that the policy is vague, subjective and misleading to the public. Its lack of clarity has been good news for large housebuilders but bad news for everyone who loves the countryside. Council for the Protection of Rural England